Destination: Canadian

Travel time from:

Austin – 8.5 hours

Brownsville – 13 hours

Dallas – 6 hours

Houston – 9.5 hours

San Antonio – 8.75 hours

Lubbock – 3.75 hours

El Paso – 9 hours

Canadian’s fall foliage display lets you leave the bustling world behind.

By Barbara Rodriguez

There is something about the drive up into the rarified air of the Texas Panhandle that invites conversation, even — miracle of miracles — from a preteen. We’ve left Fort Worth for an autumnal uplift to relieve familial stress, manifested on my son Elliott’s part by an uncharacteristic silence. I’m hopeful a road trip to Canadian’s Fall Foliage Festival will offer mobile therapy.

Day One

Near Amarillo, puzzle-piece clouds dissolve into the billowy blue tent of Texas Big Sky country. Cotton fields roll flat to the horizon, then undulate into prairie. The landscape ripples with gilded grasses, sometimes embroidered in sorghum red, until the wind-sloshed swells buck up into flat-topped mesas. Turf rips open up like a broken zipper to expose a spill of canyon. Chattering about what we might find in Canadian, Elliott and my husband Jurgen’s voices are balm to me. For an entire weekend, we are bound together in a shared love of discovery.

Panhandle roads are often ribbon straight, but we try to reroute ourselves to avoid the region’s most reliable speed bump: mile-long trains. At last we give in and let the rattle and hum of passing trains help us to slow down. We count the cars, breathing deeply. I sow fun facts about the 16 million acres of mixed grass prairie that sprout conversation about wind farms and crosswinds. Iconic isolated farmhouses inspire talk of lonely transplanted brides. We revel in roadside signs we’ve never seen before. Jurgen’s favorite is a pictograph illustrating the danger of bottoming out a trailer; I quite like the warning of low visibility due to blowing dust.

Pampa heralds the legions of Spanish dagger that Elliott used to call upside-down palm trees. At Miami we reminisce about a recent earthquake. As we pass into Hemphill County the road-kill count inspires Elliott to raise a truly existential question: If all the turkey vultures were killed, what would eat their carcasses?

Seven miles outside Canadian a dinosaur stands sentinel on a high bluff. It is Audrey, the yellow-spotted, 50-foot, one-ton steel mesh and concrete brontosaur-of-sorts built by rancher Gene Cockrell in honor of his wife, Audrey. It is a love token second only to the Taj Mahal.

Beyond Canadian’s highway storefronts is a serenity that’s more hometown than tourist destination. We’d expected the Fall Foliage Festival to mean traffic jams and crowded restaurants, but the event is more like a big family reunion. There’s a huge arts and crafts show, barbecue and home tours. But the main draw is the foliage, best enjoyed in a leisurely drive along the 12 miles of farm road to Lake Marvin.

We head to the edge of town and walk the bridge. The Canadian River Wagon Bridge was constructed in 1916 to a length of 2,635 feet. When the river changed course in 1924, the bridge was lengthened to its current 3,255 feet. Considered the longest metal truss span in the state (a technology replaced by riveted connections), it is truly a bridge to nowhere, a favored spot for strolling with babies and binoculars. Alone there, as we were, it’s a long wood-planked stretch of splendid isolation.

As we walk, the drone of wasps and cicadas grows hypnotic. Elliott, happier than I’ve seen him in days, reemerges from the distance, breathless, to announce a giant spider web. “It feels like it never ends,” he pants, as we retrace his steps to the glinting treasure.

The once mighty Canadian River appears near the far end of the bridge, a muddy S-turn moving swiftly only in a narrow channel, while lazier waters ripple across sandbars. Beneath the bridge, swallow nests like adobe cliff dwellings remind me that humans carved out shelter along the bluffs of the river in the early 12th century.

Elliott stops to eye a stink bug that puts the length of the bridge in a new perspective: “Think what that walk would be like to him,” he says.

Day Two

Rising early, I recognize a sweet, earthy feedlot smell that I associate with Stock Show week in Fort Worth. In Canadian, it is a scent as central to the town’s well-being as the smells of natural gas throughout the county. Thanks to the Anadarko Basin, Canadian enjoys the prosperity of the largest natural-gas well in the world.

But the town’s robustness also reflects its spirited frontier heritage. The red-bricked Main Street is witnessing a $1.3 million renovation; silk-stocking historic houses boast museum quality art (specifically the famed Citadelle, a former Baptist church that is now home to the Malouf Abraham family, longtime town patrons); the fully restored Palace Theatre has a state-of-the-art sound system. The town that in the 1880s had 13 saloons and no churches now has 11 churches and no saloons.

As we head out, we notice that there’s been a scenic adjustment. Overnight, as if arranged by festival organizers, the landscape has been brushed with the glorious colors of autumn. Burnished coppers, glinting golds and blushing reds that weren’t obvious yesterday are in full display. The evening’s chill has brought on a flash of foliage that is guest-worthy.

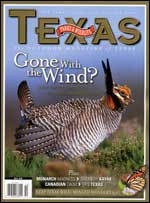

Six miles from town we bisect the Gene Howe Wildlife Management Area, 5,394 acres of grasslands and cottonwood rangeland, bordered on the south by the Canadian River. Lesser prairie-chickens occasionally can be found there, but today the sandhill uplands are still. We stop at headquarters (registration allows you access to side roads) and wend in and out to see many a Rio Grande turkey in full strut, a few prairie dogs, but nary a chicken, scaled quail or antelope. At a historic marker, we read about the discovery of pierced mastodon bones that evidenced prehistoric man’s trails here. Then it’s on to Lake Marvin in the Black Kettle National Grasslands, where we find a crowd of families making pine cone bird feeders, custom-mixing birdseed and lining up to look at the sun through a telescope. The sheer audacity of the last activity has Elliott bolting into line. The filtered show of a fiery red disk is impressive indeed.

Circling the 63-acre lake (conveniently outfitted with fishing piers) we find the Old Cottonwood Trail, heralding the landmark known as the Big Tree by Native Americans and cavalry traveling the stage road from 1870–90. The boys surge forward while I stop to admire stands of persimmons, equally loved by hogs (for forage) and early pioneers (for wine). Not quite so easy to discern, simply because of their numbers, are tracks of everything from deer to raccoon to wild turkey. Flecks of sumac berries brighten the underbrush.

Day Three

Elliott and Jurgen have sided against me in a bid to spend time at the Canadian Skate Park, a block from our cottage. Watching father and son head out, I know the weekend has been a success.

In the afternoon, no bones broken, and spirits high we head out for Lipscomb, discovering along the way the landscape that captivated Georgia O’Keeffe in the early 1900s. The broad views of draws, bluffs, canyons and mesas she painted are animated by the rolling sea of prairie grasses. Silhouetted on the horizon is a caravan of wild turkeys, 15 hens, necks extended, tail feathers down, lurching along like miniature dinosaurs.

Lipscomb, population 44, is a blip of a prairie railroad town with a surprisingly large and sturdy county courthouse in the center. The settlement once known as a cattleman’s paradise now cultivates artist studios. The mostly grass town square is home to three frontier storefronts with a winningly eccentric inventory of art, books, saddles and big personalities. Monthly art shows feature at Naturally Yours, a gallery maybe best known for the Dance Platform out back. Continuing a tradition established in July 1885, Debby Opdyke and Jan Luna opened their platform in 1996 for family dancing and Prairie Kitchen dinners every third Saturday, June through September.

We’ve come in search of posole, chile and cornbread and the Annual Lipscomb Studio Tour, held each October. At Naturally Yours we find Gerald L. Holmes, illustrator of John Erikson’s Hank the Cowdog series, sketching in the front room and folks lining up for chow in the back. We settle in to chat and chew, totally entranced by the locals and their knowledge of area history (settlers here were Germans and Russians lured by offers of free passage and abundant land).

Before leaving town we stop to visit with J.W. Beeson, saddlemaker and cowboy poet, as fine a teller of tales as he is a leather artisan. Finally, we hit the lonesome road to Higgins and the Prairie View Furniture studio of Doug Ricketts, a one-of-a-kind woodworker and artisan, who redefines the expression “creative reuse.” He recycles hardware and machine bits, iron key plates, stove legs and found objects into museum-worthy tables, cabinets and furnishings. In one remarkable white oak cabinet, a John Deere Crust Buster’s tine functions as a door pull, a section of the diesel tank a door panel.

Then, too early, it’s time to head back south and settle into our next adventure. I ask Elliott what wisdom he has gleaned from the journey. He closes his eyes and thinks. Then, with a smile he says, “Opportunities lead to opportunities,” he says. Indeed.

Details

• Canadian Visitors’ Center/Chamber of Commerce: (806) 323-6234, www.canadiantx.com

• Gene Howe Wildlife Management Area: (806) 323-8642, www.tpwd.state.tx.us/wma/wmarea/genehowe.htm

• Palace Theatre: (806) 323-5133, www.palacetheatre.com

• Naturally Yours Gallery & Dance Platform: (806) 862-2900

• Prairie View Furniture: www.dougricketts.com