Courage and a Rope

Big Bend canyoneering provides high adventure for expert rock climbers.

By Russell Roe

Ky Harkey pointed to an unnamed canyon in one of the most remote corners of Big Bend National Park and said that was where we were going.

In the satellite map image, the canyon sliced a dark, jagged gash across the Mesa de Anguila on the westernmost edge of the park. The tall, narrow walls of the gorge blocked out any light, keeping hidden any mysteries inside.

The canyon was just another scar in the twisted, tortured geologic history of Big Bend, but it was the kind of deep, dark scar that we hoped would hold what we were after.

As a climber and a backpacker, I love exploring narrow canyons called slot canyons in places like southern Utah. I was hoping to find a similar kind of canyoneering experience in Texas, and Harkey said the canyon he was pointing to on the map required six rappels to get through it.

Sounded like good adventure to me.

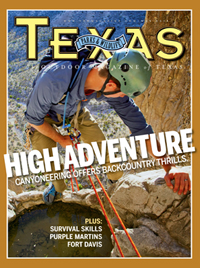

Ky Harkey rappels a section of a canyon in Big Bend National Park.

Canyoneering is a method of traveling through canyons using techniques such as climbing and rappelling. A canyoneering adventure can be as simple as downclimbing a couple of short ledges or as involved as rappelling down hundred-foot waterfalls, climbing on slick, exposed rock and swimming through frigid waters.

What we found over the next few days in Big Bend were some beautiful and challenging slot canyons, incredible vistas, miles of rugged hiking and one long, unnerving rappel that took us literally to the end of our rope.

Our plan was to hike six miles to the top of the Mesa de Anguila and set up camp in an area near a water hole called Tinaja Blanca. We hoped to explore the Tinaja Blanca canyon the first day, attempt our destination canyon the second day and descend through a third canyon on our way out.

The Mesa de Anguila sits isolated from the rest of Big Bend National Park, on the far western edge and away from the main attractions of the Chisos Mountains. Most people know it as the formation that creates the U.S. side of the Rio Grande’s Santa Elena Canyon. The mesa’s limestone sets it apart geologically from the unstable volcanic rock found in most of the park. There’s no campground, and the one main trail going in and out from Lajitas means access is limited. Trails on the mesa can be overgrown and hard to follow. It’s the least-visited part of the national park. I was starting to realize, too, that the canyon we were planning to visit was probably one of the least-visited areas in the least-visited part of the park.

Backpackers on the mesa are encouraged to pack in all their water. Some backpackers take their chances on finding water in the mesa’s tinajas, or rock water holes, and if they don’t find any, they’ll cut their trip short and hike right back out.

It’s unforgiving desert terrain, but those willing to brave it will find solitude, rugged desert beauty and sweeping views into Mexico.

For our December trip, we had weather on our side. The forecast called for sunny skies with highs in the 60s and lows in the 40s. It doesn’t get any better than that for winter desert hiking. Plus, the forecast said there was a zero percent chance of rain.

“Zero percent chance of rain when you’re dropping into a slot canyon sounds pretty good,” said Harkey, who works for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s state park education and outreach programs.

After setting up camp, we began our descent of the Tinaja Blanca canyon as a warm-up for our big canyon day the next day. It’s a fairly short canyon, and we figured it wouldn’t take more than an afternoon. One big worry, though, loomed over us as we entered the canyon. The only trip report we had seen on Tinaja Blanca said the final drop at the mouth of the canyon was 200 feet tall. The rope we brought for rappelling was, well, 180 feet. We figured we would make it to the final drop and assess the situation once we were there.

Starting the descent of the first canyon.

Harkey and I have been rock climbers for years, and we were confident that our climbing and rappelling experience gave us the grounding necessary to navigate the canyons we were facing. Our main challenge was going to be getting TPWD photographer Brandon Jakobeit, who had rappelled only once before during a practice session, safely through the canyons.

We set up a rope to assist Jakobeit down a steep section at the beginning of the canyon and set up a couple of short rappels lower in the canyon. Soon enough, we found ourselves at the big drop. Our anxiety levels quickly spiked. It was a long way down to the ground below. We couldn’t tell how far. Questions raced through our minds. Could we rappel 180 feet and downclimb the final 20 feet if needed? Would the stretch in our rope buy us a few extra feet? Did the 200-foot rappel start from the upper ledge where we were standing or from a lower ledge we could see 15 to 20 feet below us? And, finally: This was our warm-up?

We set up a rappel, and Harkey volunteered to take a look over the edge. He hooked in, triple-checked his gear and slowly started to lower himself down. We watched nervously as he passed the lower ledge and found himself at the top of what would have been a 200-foot waterfall if water had been coursing through the canyon. He still couldn’t tell if the rope reached the ground. A hummingbird buzzed by, stopping momentarily near Harkey’s helmeted head. I could imagine the wheels turning in Harkey’s mind as he assessed the risks. He kept looking down the wall and then back up at us, down the wall and back up at us.

His nervousness got the best of him. “I’m leaning toward not doing it,” he yelled up at us. A reasonable decision. As we talked it out, though, we figured that if he kept lowering and the rope didn’t reach, the worst outcome would be that he’d have to ascend back up the rope, and we’d have to hike and climb back up the canyon. He decided to keep going, but first, he switched the rappel station to the lower ledge to gain a few extra feet. He lowered himself a bit, and lowered some more. Finally, when he was about a third of the way down the wall, he saw the rope reaching the ground.

“It goes!” he shouted up to us in relief.

Jakobeit and I then made the long rappel, which turned out to be less than 200 feet. It was long enough, though, that our metal rappel devices were too hot to touch when we reached the bottom.

“That was good adventure,” Harkey said.

“I was just happy to get off that ledge,” Jakobeit said.

Harkey on rappel at the big drop.

The next day we awoke, ready to tackle our destination slot canyon, which, it turns out, does have a name, though it’s not marked on any maps I’ve seen: Joel’s Canyon. Harkey had helped lead a university-affiliated trip to the canyon a few years earlier but had run into trouble. A member of the group got injured earlier in the trek, and Harkey had to stay with him while the rest of the group went to the mesa. Harkey was eager to get to the canyon to see what he had missed. I knew the feeling. Whenever I’ve missed out on an adventure, or barely missed making a mountain’s summit, it makes me want it even more. It lights a fire you can’t put out. I was happy to help Harkey cross this off his list.

We hiked down the trail and dropped into the arroyo. Soon, the walls started to get higher on either side of us, and the canyon started to get narrower. The temperature dropped several degrees as we left the warmth of the sun. We found ourselves in a section requiring some downclimbing, and we stopped to put on our harnesses and helmets and get out the rope.

Descending a canyon for the first time involves a certain amount of apprehension. We felt prepared, yet we didn’t know what lay ahead. Our nerves jangled like the metal gear on our harnesses.

Harkey scouted ahead while I made sure Jakobeit got down the first section. As I’ve learned from friends and family members who get mad at me when I take them to places out of their comfort zone, what I consider to be a reasonable downclimb can be terrifying to people who don’t have much experience doing it. This was definitely out of Jakobeit’s comfort zone. He said he felt comfortable rappelling, but the short, isolated sections of climbing like this one still unnerved him. Plus, he had the burden of carrying all the camera equipment and taking photos along the way.

“That was some good scrambling just to get down here,” Harkey said when we caught up to him.

I was learning to decode Harkey’s language. “Good scrambling” meant you better have some rock-climbing experience to even attempt it, and even then, you’ll probably be scared and could possibly fall into a 15-foot-deep pit. “Good adventure,” another Harkey-ism, meant you might get lost a few times on the hike, attempt a 200-foot rappel with a 180-foot rope or possibly get leapt on by a mountain lion.

Getting to the first rappel required crawling through a rock tunnel before arriving at a medium-sized ledge. The first rappel was a two-step process by which we descended down a wall, skirted around a pool of water and then descended another drop beyond the end of the pool. This was one of our most challenging rappels. None of us wanted to fall in the water and risk hypothermia.

The author rappelling barefoot after skirting around a pool of water.

The second rappel started a theme for a few more rappels: A big boulder blocked the way down the canyon, and we had to rappel off of it to continue.

It was exciting to explore a canyon that few people had seen before. The soaring, narrow canyon walls, sculpted limestone formations, beautiful pools of water and ribbon of blue sky above created a perfect setting. We experienced competing desires to hurry through the canyon and to slow down and savor our time there. Every turn of the canyon brought something new as we explored caves, jumped from boulder to boulder, traversed along ledges and scrambled over and under rocks. At one point, the canyon opened wider, filled with huge, truck-size boulders. I wondered how it was going to be possible to make it through such a massive boulder field.

Harkey’s deft ropework kept everything humming along. Whenever it was my turn to coil the rope and throw it down for the next rappel, it often would end up in a jumble of tangles or land between two boulders in some unknown hole. Whenever Harkey coiled and threw it, it would unfurl in graceful descent until landing perfectly on top of whatever boulder he was aiming for.

The fourth rappel proved to be a turning point. Until then, Harkey and I felt as though we could climb back up the canyon if we needed to, even up the parts we had rappelled down. The fourth rappel, though, brought us to a section too high and too steep to climb back up. When we pulled the rope down, we were committed to making it all the way through the canyon.

Harkey in a narrow section of the slot canyon, with the mouth of the canyon in sight.

The fifth rappel was the most beautiful — down a long, dry waterfall of water-sculpted limestone, with a hot-tub-size pool of water at the bottom. I didn’t want to disturb the water, or get wet, so I rappelled down as close as I could to the pool, kicked out from the wall as hard as I could and landed on dry ground. Jakobeit, who was now rappelling like a pro, repeated the same maneuver.

The sixth rappel was at the mouth of the canyon, and we could see the desert floor and the gorges of the Rio Grande spreading out before us. As a canyon wren serenaded us with its cascading song, we lingered for a while, not yet ready to leave the amazing canyon we had just experienced.

I was the last one to rappel. “This is about as close to Utah as you can get in Texas,” I said after I pulled the rope down to coil it.

As we hiked back to camp, we savored the day’s experience and watched the sun set and the full moon rise over the mesa.

The next day, we packed up camp and headed to Tinaja Lujan, another beautiful slot canyon. There, we scrambled over rocks and around pools and rappelled down a couple of steep sections — made harder with our full backpacks. At one point, the canyon got so narrow that you could reach out and touch both sides.

The hike out was rough. The trail was faint, and everything in the desert is thorny, scratchy or prickly. Rock cairns marked the way every 20 or 30 yards, but they were hard to spot. It felt like following breadcrumbs through the desert. We lost the trail several times but always managed to find our way back, happy to finally reach the car.

It was, as Harkey would say, good adventure.

A Word of WarningClimbing, rappelling and canyoneering are inherently dangerous and should be performed only by people with the proper training and experience. Rock quality in much of Big Bend National Park is poor. Exploration of narrow canyons is especially dangerous during periods of rain, when the threat of flash flooding increases. The Mesa de Anguila area of Big Bend is remote and isolated. Treks there are recommended only for experienced desert backpackers. Water sources are unreliable; park staff urges backpackers to pack in all their water. |

» Like this story? If you enjoy reading articles like this, subscribe to Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine.