Wild Thing: Herping West Texas

Enthusiasts flock to Sanderson for annual SnakeDays event.

By Andy Gluesenkamp

While some people do their best to avoid contact with snakes in the wild, a group of herpetological enthusiasts — known as “herpers” — will gather together May 30 through June 1 to search for snakes and other wildlife along the roadcuts near a tiny Texas town.

Each year in late May or early June, Herpathon (aka SnakeDays) draws hundreds of visitors to Sanderson, a town of fewer than 1,000 residents, to participate in a weekend of educational lectures and a trade show, punctuated by a nightly snake hunt. These herpers don’t seek to kill the snakes. Most don’t even handle them. Like birders, they want to observe the species found in the area, adding to their life lists and firsthand knowledge.

A recent change to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department regulations allows individuals to collect or handle reptiles and amphibians from public rights of way as long as they have a valid hunting license, a $10 reptile and amphibian stamp and a reflective vest. Armed with headlamps, small groups of herpers can be seen looking for snakes and other wildlife that live in and around crevice-riddled exposures of roadcuts near Sanderson.

The elusive gray-banded kingsnake (Lampropeltis alterna) is the primary target on most of their lists during the event.

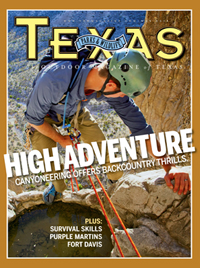

.jpg)

Gray-banded kingsnake.

This colorful and variably patterned snake is found in rocky areas in the Chihuahuan Desert of West Texas and northern Mexico, where it feeds primarily on lizards and small mammals. Gray-bands occur in a boggling array of color phases with a great deal of geographic variation.

Experienced herpers can determine a kingsnake’s origin from its appearance. Individual snakes may be gray with broad orange saddles, orange with red saddles, gray with black bands, blue with black bands, speckled, diamond-blotched … a dazzling array.

Finding a gray-band is the highlight of any herping trip to the Trans-Pecos, yet many herpers spend many seasons, sometimes decades, without seeing one. The gray-banded kingsnake is not particularly rare, but its secretive habits and the remoteness of its habitat are largely responsible for its reputation as elusive.

Captive breeding efforts have resulted in this snake becoming common in the pet trade, with breeders providing locality- or pattern-specific captive-born offspring at prices well below that of a tank of gas. As a result, collection pressure for this species is negligible. Most hobbyists just want to see one in the wild; the photographers among them place great value on in situ photographs of snakes, without manipulation or staging.

Other species commonly encountered on roadcuts in the Trans-Pecos include the beautiful and graceful Trans-Pecos rat snake, the rock rattlesnake, the Trans-Pecos copperhead (yes, a copperhead that lives in the desert) and various species of nocturnal snakes. Texas banded geckoes, centipedes, millipedes and tarantulas are also commonly encountered.

In addition to information, camaraderie and herping opportunities, Herpathon 2014 is also a fundraising effort, with all proceeds going to TPWD’s Reptile and Amphibian Research and Conservation Fund. This fund is used to support citizen science and survey efforts for rare snakes in other parts of the state.

For more information, visit www.snakedays.com.

Related stories

iNaturalist Lets Citizen Scientists Aid Conservation

Keep Texas Wild: S-S-Snakes Alive! (PDF)

See more wildlife articles on TP&W magazine's Texas wildlife page