“While we lived at San Pedro Springs Park ... as my brother and I started to school we walked under one of the park trees and saw an immense wild animal spread out on a big limb, staring at us and showing his fangs. We didn’t know what it was, but we did know it wasn’t safe to let a thing like that run wild in our neighborhood. We yelled for Father to come with his gun... It required two shots at close range to end the animal, which proved to be one of the largest jaguars ever seen anywhere in Southwest Texas.”

— San Antonio Express-News, April 18, 1922

The Texas jaguar story quoted above was told by prominent San Antonian Gustave Duerler, when recalling his childhood in the 1860s. San Pedro Springs Park is now near downtown San Antonio, but the area was on the edge of the vast Texas wilderness at the time. Jaguars, black bears, wolves, bison and ocelots all roamed the Hill Country.

Because of their reclusive habits, jaguars were rarely seen, but stories like Duerler’s are not uncommon. Jaguars have lived in Texas since the Pleistocene, and, with the exception of the Great Plains, there are historical records of the big cats across most of the state. Famous artist and naturalist John James Audubon visited the Republic of Texas in 1836 and commented about jaguars:

“This species is known to exist in Texas, and in a few localities is not very rare, although it is far from being abundant throughout the state.” He continued, “In a conversation with General [Sam] Houston at Washington City, he informed us that he had found the jaguar ... abundantly on the headwaters of some of the eastern tributaries of the Rio Grande, the Guadalupe, etc.” Houston also claimed to have seen one “east of the San Jacinto River.”

The last jaguar in Texas was documented as recently as 1948. On April 25, the Corpus Christi Caller-Times ran an article titled “Tough Customer: 121-Pound Jaguar Killed on Farm Near Kingsville.” The author boasted, “South Texas has everything, even jaguars! But there is one less jaguar in this area now, after Richard Cuevas, worker on the Bob Ferguson dairy farm near Kingsville, killed one of the big cats.”

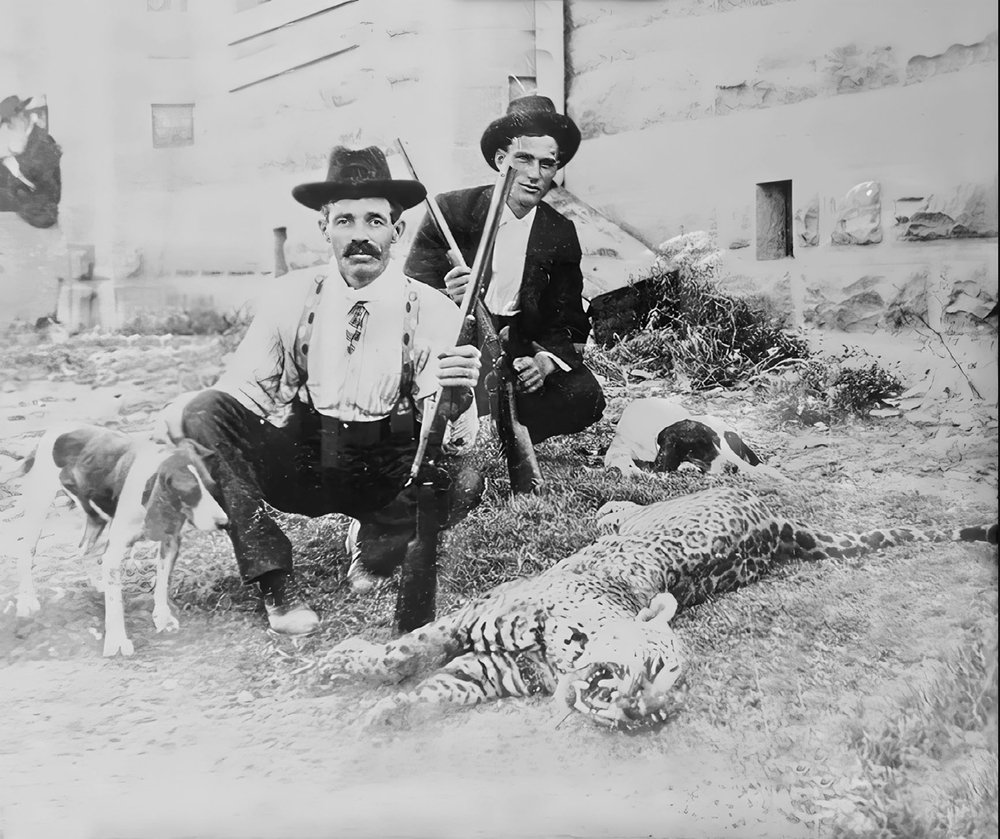

An image of a small girl sitting on the abdomen of the prostrate jaguar was included with the story. Pioneering King Ranch biologist Valgene Lehmann, who took the photo, also did an autopsy on the animal. The Kingsville jaguar was a small male. All native jaguars had been driven south by settlers, so most of the 20th-century cats documented in Texas were likely young males from Mexico in search of territory.

Biologists estimate that almost 5,000 jaguars live in Mexico today, and over the past decade three males have even been seen on camera traps in southern Arizona. None of this Mexican population has crossed back into Texas, so we have to rely on old hunting photos and newspaper stories to learn more about these impressive cats. I’ve scanned thousands of newspaper archives and discovered reports of at least a dozen native jaguar sightings.

The 1903 Goldthwaite cat is likely the most well-known native jaguar because of its prominence in Vernon Bailey’s 1905 Biological Survey of Texas. The harrowing story of Homer Brown’s hunt is legendary among hunters and historians. This is an excerpt from Brown’s letter to Julia Kemp about the incident:

“In regard to the jaguar, we killed him Thursday night, September 3… Henry Morris came to go hunting with me that night. We three took supper at my home and then started for the mountains 3 miles southwest of Center City, where we started the jaguar just at dark. We ran him about 3 miles and treed him in a small Spanish oak. I shot him in the body with a Colt .45. He fell out of the tree and the hounds ran him about half a mile and bayed him. I stayed with him while Morris went to Center City after guns and ammunition. In about an hour and a half, he came back and brought several men with him. So then the fight commenced. We had to ride into the shinnery and drive him out, and we got him killed just at 12 o’clock that night. We commenced the fight with ten hounds, but when we got him killed there were three dogs with him, and one of them wounded. ... It got hold of Bill Morris’s horse and bit it so bad it died from the wounds.”

While it’s hard to say how embellished this story is, we do have concrete records of the cat. The Goldthwaite jaguar skull is currently housed in an archive at the Smithsonian Institution.

Six years later, another jaguar was killed in London, Texas, north of Junction near the Llano River. Two young boys exploring with their dog stumbled into the big cat hiding in a cave. After getting into some trouble, they retreated and called in armed adults. The story reads like an early 20th-century children’s adventure. This is from one of the boys’ son’s retelling in the Junction Eagle:

“Pa and Charley were scared to death. They had never seen a jaguar and didn’t even know what it was they were seeing. They just decided they’d better run for their own lives and try to get help as fast as their legs could carry them.”

More recent encounters include the 1946 jaguar that was tracked down by ranch hands on the San Jose Ranch near McAllen. Today, it’s almost impossible that a jaguar could cross into that part of the Rio Grande Valley because of agricultural and urban development. There isn’t a clear path for jaguars to return to Texas anymore, and they are considered long-extirpated.

We may not see them in our forests anymore, but it’s essential that they live on in our collective memory. Texas was once home to an abundance of megafauna, and old hunting stories like these give us a glimpse of how truly wild our state was.