I was dozing in the back of my 4Runner at the Judge Roy Bean Visitor Center in Langtry when my phone buzzed.

To the east, the rising sun threw long shadows across the empty gravel parking lot and the tawny Trans-Pecos badlands. Langtry was never much of a metropolis, but Judge Bean, who ran the local saloon, managed to bring the town some renown as “the Law West of the Pecos.”

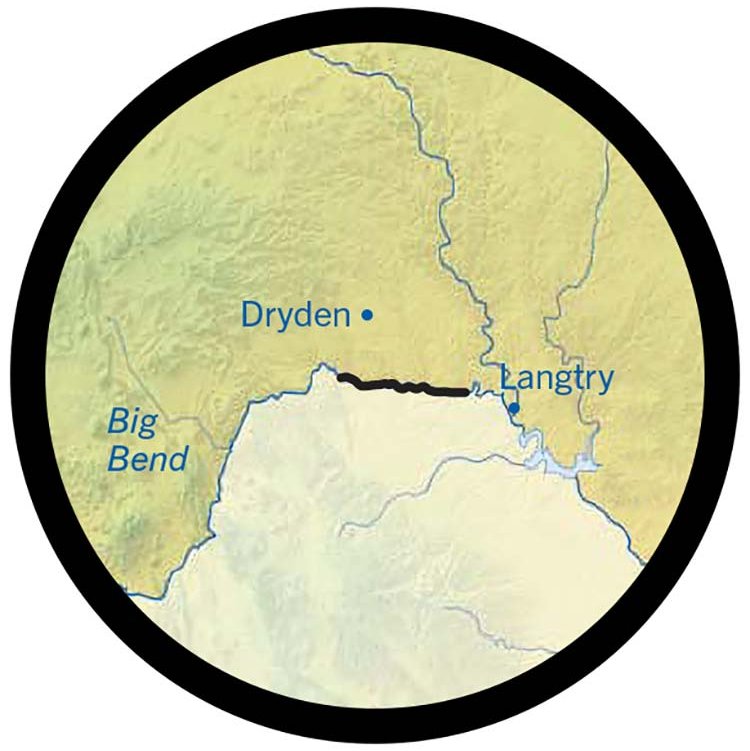

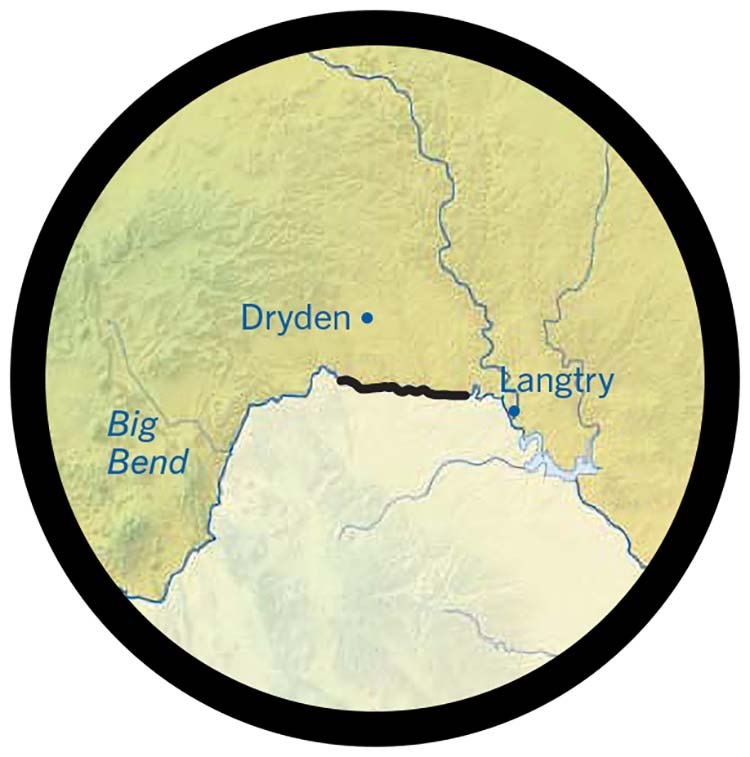

After shaking out my bedroll, I poured my coffee and studied the mountains of Mexico in the distance. Somewhere unseen beyond the plateau ran the Langtry Reach, a lonely sweep of river amid the rough canyons carved by the Rio Grande above Lake Amistad, fed by underground springs about 100 miles east of Big Bend National Park.

With reports last year that sections of the river in Big Bend had run dry, I reached out to veteran West Texas outfitter Charlie Angell, owner of Angell Expeditions. He observed sadly that drought conditions were limiting trips inside the park, but thanks to those springs, we could get on the water of this lower section.

Now, Angell's assistant, guide Tony Drewry, a talented photographer and volunteer firefighter I have known for years, was texting me the coordinates for our rendezvous, warning that Angell was impatient for the two-hour drive to the put-in.

“I've been guiding on this river for 18 years,” Angell says. “Before that, I spent seven years playing and paddling it privately. I've never seen it this low. It's horrid. The drought we're in is greater than the drought of 1200 A.D. that drove the Anasazi out of their cliff dwellings.”

Extreme drought led to the Rio Grande running dry in recent years.

Photo by Sonja Sommerfeld.

Extreme drought led to the Rio Grande running dry in recent years.

Photo by Sonja Sommerfeld.

Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention. Worried about his evaporating income, Angell had come to learn about an underground river beneath Sanderson County, which kept the water volume in these canyonlands on average four to five times higher than in the park. Angell arranged access with local landowners, and for the past two years has been leading occasional canoe trips down this drought-resistant descent.

By noon, we had reached the put-in and started strapping all manner of gear into the canoes. After a quick lunch of cheese and cold cuts, we stepped into the current and said goodbye to civilization. Over the next 55 river miles, we would not see another human being on the Langtry Reach, a portion of the Rio Grande protected since 1978 under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, a law safeguarding the river's value as a natural, cultural and recreational resource.

Being a fall trip, the afternoon was overcast but still warm, and the cool water was seriously refreshing. In addition to Angell, Drewry and a third guide, our crew included history podcaster and entrepreneur Brandon Seale of San Antonio, who was joined by two college classmates who had flown in from out of state. In his own canoe rode Patrick Black, a client of Angell's. Black, a former National Geographic security consultant, shared tales of working archeological sites in Latin America. I shared my boat with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department photographer Chase Fountain. Before too long, Seale and his buddies — and later Fountain and I — all swamped our boats, a sharp reminder that even gentlest of rapids can be pushy when you're handling a fully loaded canoe.

Fully loaded canoes can be hard to manage in swift water.

Fully loaded canoes can be hard to manage in swift water.

By the end of this first day, having forged a path through 16 miles of the Rio Grande, a murky green ribbon punctuated by deep pools and gravel bars, we were mostly just happy to have survived. One thing that made an impression was the abundant carrizo cane. Also called border bamboo, this invasive plant can grow as tall as 30 feet and persists the length of the river despite widespread control efforts. It's associated with loss of biodiversity, among other problems. Running headlong into the reeds occasionally rained spiders down upon us.

As night fell, so did the temperatures. I fell asleep with the Milky Way shining overhead, reflecting on what Angell had said earlier. “I can see a day when this is the only trip we do,” he told me. “Too many people are taking too much water. I don't see another solution.”

The paddling crew at the put-in for the Rio Grande's Langtry Reach; a paddler navigates a weir; Charlie Angell leads the way down the river; the Langtry Reach, downstream from Big Bend, is floatable even in dry times.

Chase Fountain

The paddling crew at the put-in for the Rio Grande's Langtry Reach; a paddler navigates a weir; Charlie Angell leads the way down the river; the Langtry Reach, downstream from Big Bend, is floatable even in dry times.

Chase Fountain

The paddling crew at the put-in for the Rio Grande's Langtry Reach; a paddler navigates a weir; Charlie Angell leads the way down the river; the Langtry Reach, downstream from Big Bend, is floatable even in dry times.

Chase Fountain

The paddling crew at the put-in for the Rio Grande's Langtry Reach; a paddler navigates a weir; Charlie Angell leads the way down the river; the Langtry Reach, downstream from Big Bend, is floatable even in dry times.

Chase Fountain

The paddling crew at the put-in for the Rio Grande's Langtry Reach; a paddler navigates a weir; Charlie Angell leads the way down the river; the Langtry Reach, downstream from Big Bend, is floatable even in dry times.

Big River

It's a long way from the headwaters of the Rio Grande to the Langtry Reach as the river makes its way to the Gulf. Starting 1,900 miles upstream from the ocean in southern Colorado, the drainage is unique in North America as perhaps the only waterway that crosses from the Pacific side of the Continental Divide to the Atlantic. Along its path, the Rio Grande finds its way to New Mexico, where the steep canyons outside Taos are a tourist attraction in their own right, with anglers chasing trout and rafting operations running trips in spring. Yet, since the completion in 1916 of Elephant Butte Dam outside the town of Truth or Consequences, 125 miles north of El Paso, much of that water stopped flowing to Texas.

Canoes navigate a rocky section.

Chase Fountain

Canoes navigate a rocky section.

Chase Fountain

I have visited many of those points to the north, taking time in the San Juan Mountains to contemplate my own relationship to the great river. Moreover, I have traveled to the river mouth at Boca Chica on the Texas coast, and reported on the seasons when sandbars were exposed as flows dropped, blocking the outflow of the Rio Grande. I have also worked my way along the river as it passes through Big Bend, paddling Santa Elena, Marsical and Boquillas canyons at various times over the past decade. I spent nearly a week on the Pecos River, and canoed the Devils River too. Every visit brings new surprises.

To wit, wildlife sightings along the Langtry Reach were frequent and fun. Among the birds we spotted were solitary sandpipers, belted kingfishers, eastern phoebes (acrobatically picking insects out of the air), an immature golden eagle and a kettle of vultures wheeling beneath the bright blue sky. Both teal and grebes cruised in the current. Mammals included white-tailed deer, exotic aoudad sheep, gray foxes and porcupines. As we approached the high walls of the Herradura, a Spanish word that translates to “horseshoe” (and also a popular tequila brand), a herd of feral hogs swam across from Mexico and crashed through the carrizo. Encountering these wild creatures served as a reminder that across such an arid landscape the river is as much an important ecological resource as an economic one.

In 2024, the challenges faced along the Texas Rio Grande made headlines. “How Do You Paddle a Disappearing River?” asked an article in The New York Times that looked at recreation and conservation on the river; the Big Bend Sentinel in Marfa followed with an account from one of its staffers, a part-time river guide named Sam Karas, who appeared in photos dragging her canoe over the rocks. “A day on the river is always a beautiful day,” Karas told the Sentinel, “but while it's hot outside it can be pretty miserable to drag the boats around. So wait for nicer weather or deeper water if you can.”

After I returned home from the trip, I made a few calls of my own. In particular, I reached out to Raymond Skiles, a retired wildlife biologist who spent three decades with the National Park Service, mostly at Big Bend. Skiles' social media posts showing mud puddles and dry river beds in the park made it impossible to ignore the fact that this 21st century drought remains extreme.

“Absolutely, it's not normal,” Skiles told me. “The episode last year was episode three. The first time I saw this phenomenon of the river being so low was in 2013. And that's not just my impression, that's what the data says. We've had monitoring on the river since 1900.”

Complicating matters is that historically the United States has counted on Mexico to help boost instream flows via the Rio Conchos, which comes down from the Sierra Madre Occidental and joins the Rio Grande near Presidio. Despite long-term agreements between the two nations, Mexico is behind on its obligations by an estimated 1.75 million acre-feet of water. This April, Mexico agreed to deliver more water to help pay off its debt, and has so far delivered roughly 500,000 acre-feet, with another 420,000 acre-feet promised by October 2025, roughly half its obligation. Like the Texas side of the river, Mexico is experiencing extreme drought that makes meeting the treaty's goals almost impossible in this shared basin.

“The Rio Conchos is going through what we did to the Rio Grande,” Skiles explained, referring to how dams and allocations have depleted rivers on both sides of the border. “It's the death knell.”

For Skiles, the matter is deeply personal. His grandfather ran cattle along the Rio Grande between Dryden and Big Bend.

In the 1930s and '40s, around the time the national park came into being, the old-timers were taking river trips in wooden boats. In the 1980s, he added, inflatable rafts were widely employed to handle the rapids of Santa Elena Canyon. In recent years, canoes and kayaks have navigated the depleted river. “I find it astonishing that the National Park Service and the outfitters continue to put attention on the river when there's no longer any water,” he says. “So I wanted to take pictures for posterity.”

The paddlers make camp along the riverbank.

The paddlers make camp along the riverbank.

Uncertain Future

After a couple of days on the water, our nine-man expedition found the stoke in their stroke. With more springs percolating through unseen limestone formations bolstering the current, not to mention lighter loads thanks to the food and drink we'd consumed, we were moving quickly. Nobody forgot the soakings of the first day, but we now came into the turns with speed to maneuver through the corners like slalom skiers taking the gates, staying off the walls and — for the most part — out of the reeds. We shot out of a horseshoe bend beneath the sharp eye of what appeared to be a peregrine falcon, and found our final camp on a rocky beach.

Of course, all the good feelings were offset by the unspoken dread that if Angell and others turn out to be on the money, paddlers must prepare themselves to say goodbye to one more river. Barring a radical shift in regional weather, most modeling shows hotter, drier systems across the entire Southwest, including Big Bend, which means Texas may soon see the day when the Rio Grande no longer reaches the sea. Just the same, surrounded by sunburned comrades, our spirits buoyed by adventure, I found that hope remained within reach.

Paddlers break out the instruments for some campsite entertainment.

Paddlers break out the instruments for some campsite entertainment.

“That treaty made the Rio Grande the boundary,” Angell says. “This was before they really understood the water rights, and it said the river shall remain open for the purpose of recreation, enjoyment and commerce. From the very start, we agreed to be good neighbors.”

Night falls at camp along the river.

Chase Fountain

Night falls at camp along the river.

Chase Fountain