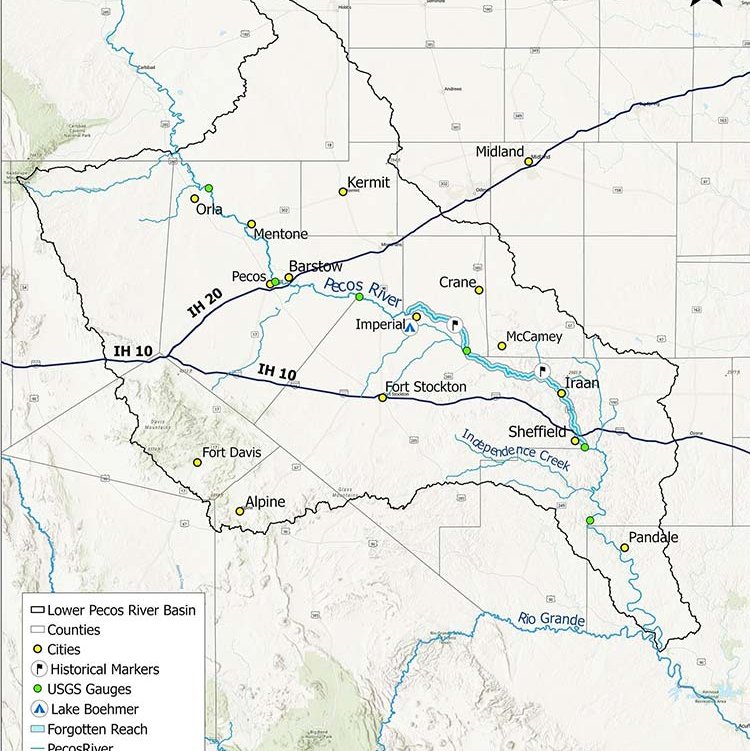

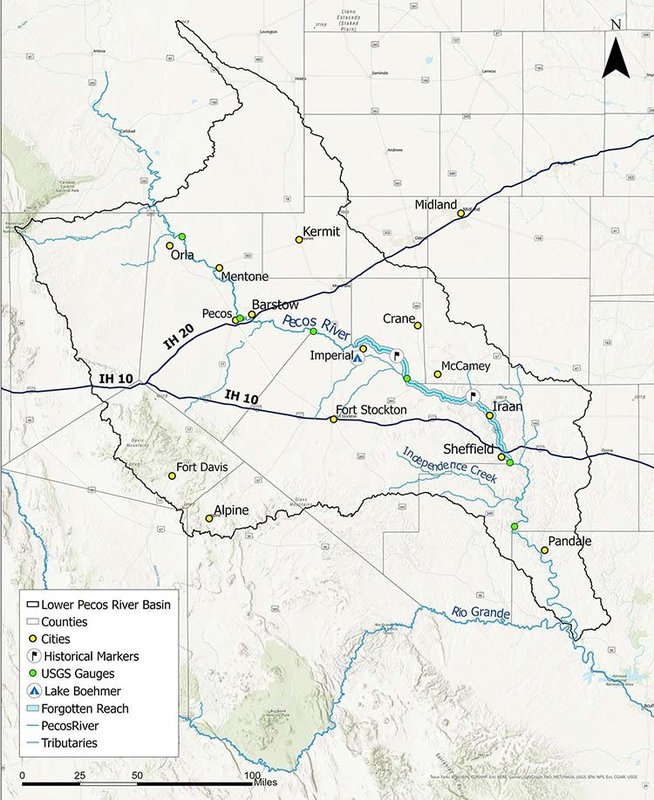

Historically, the Pecos River was a formidable presence all up and down its nearly 1,000-mile traverse.

Along the lower Pecos, near its confluence with the Rio Grande, dramatic, impassable cliffs flank its edges. Along the rest of its length in Texas, steep banks, quicksand and unpredictable currents funneled travelers through one of few passes like Horsehead Crossing, near the modern town of Girvin.

The current was deceptively swift. In fact, the legend of Pecos Bill begins when, as an infant, he was lost as his parents attempted to cross the river. Lore has it that Bill, unlike the many real people who have lost their lives to the wild river, was picked up by a pack of coyotes who raised him as their own.

As the Pecos crosses under Interstate 10 near Sheffield, it undergoes a dramatic change. Independence Creek and other streams provide a surge of spring-fed water, and the river courses between high canyon walls past ancient pictographs.

Above Interstate 10, however, the Pecos faces great challenges. Human interventions such as irrigation, impoundment, livestock grazing and overpumping of groundwater have drastically changed the appearance of the river. The surrounding watershed is contained largely within one of the country's busiest oil-producing regions. The climate is hot and dry, with average rainfall of 10 inches a year, and increasingly common drought has taken a further toll.

In the stretch from Imperial to Sheffield, communities are now doing their best to give this so-called Forgotten Reach the respect it deserves.

Helping Hands

The Friends of the Pecos River is one player in a collective effort to restore the river to a healthier state. The nonprofit focuses specifically on the Forgotten Reach of the river.

“The Pecos River is very complex. The landowner culture, the geology, the land uses and the issues all change as you go down the river,” says Christy Muse, executive director of Friends of the Pecos.

The Friends of the Pecos isn't alone. Julie Lewey is the Lower Pecos and Devils River program director for The Nature Conservancy and leader of the informal Pecos Partners, a growing group of landowners and conservation practitioners who care about the future of the Lower Pecos. Together, these groups are developing a wide body of research that will inform future conservation efforts.

Their goals? Improved water quality and quantity, increased land stewardship and community involvement, better access for outdoor recreation and enhanced educational opportunities through schools.

In the past, the Pecos River flowing through Texas was wide and shallow, stretching 65 to 100 feet from bank to bank and up to 10 feet deep, according to early travelers.

Beginning in the late 1800s, settlers occupying the Chihuahuan Desert established irrigation lines in the flatter, shallower section of river north of Sheffield. Later, in 1936, completion of the Red Bluff Reservoir at the Texas-New Mexico border led to regulation of streamflow. By the mid-1980s, more than 400,000 acres in the valley were devoted to growing crops like cotton, alfalfa, grain sorghums and cantaloupes. Irrigation of those crops uses over 80 percent of the groundwater resources of the Pecos valley. In addition to decreased streamflow, water quality has been declining, too, with the river characterized by high salinity levels and algae blooms.

By the turn of the 21st century, the river in the Forgotten Reach had arrived at its current state: a narrow and shallow trickle, except during heavy thunderstorms when it roars back to life with a cry of vengeance.

A new park in Iraan provides an outlet for river recreation.

A new park in Iraan provides an outlet for river recreation.

A Park for the People

In the past, residents along the Forgotten Reach visited the river through private access points and road crossings, but they had few places to come together around the river. Meandering through rugged hills, the Pecos was not central to the heart of their communities.

In 2017, Mickey Jack Perry, a Pecos County commissioner, began work to solve this problem. He and his construction foreman, Dimas Gonzalez, set about converting a riverside piece of county-owned land in Iraan into something the public could come together around. Over the past several years, they've spent countless hours working to clear brush, install park infrastructure such as picnic tables, a pavilion and bathrooms, planting native species and making other improvements across the park's 50-or-so acres.

“I have a lifelong love of water,” Perry says. “It just killed me that it was right there the whole time, just out of reach. Now, we've given [the community] a place to go do something outside.”

The Iraan Pecos River Park is now a popular local destination for swimming, fishing and kayaking.

In 2024, Pecos County received financial assistance to further improve the park from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department via the Habitat and Angler Access Program (HAAP). This grant program supports community partners who aim to restore and enhance freshwater fish habitats and improve access to public waterways in Texas.

With the river's diminished flows, only a few species of fish can survive in this stretch of the Pecos. The Gulf killifish is one of those few — although the Pecos River is more than 500 miles away from the fish's native habitat in the shallow, saltwater marshes of the Texas coast. The fish was likely introduced as a baitfish and has since made its home in the river. Local anglers have found enjoyment with this little fish, and it's quickly become a favorite.

Gaby Tamez, a TPWD watershed biologist, is the HAAP project lead for the Iraan Pecos River Park. Eventually, Tamez would love to see more native species of fish like Rio Grande cichlids stocked into the river to further increase angling opportunities.

“Iraan is like a world unto its own,” she says. “It has its own unique ecology, history and characteristics. It's beautifully perfect in its own way.”

She says the Iraan Pecos River Park is especially precious because outdoor opportunities in the region are rare.

“Recreation allows people to discover the benefits of the outdoors, and the best way to cultivate that appreciation is in their own communities,” she says. “If we can help build curiosity and get people in that stewardship mindset, then they'll form a love of conservation that they'll then take the next level on their own.”

Students from the local high school participate in water and soil testing.

Maegan Lanham

Students from the local high school participate in water and soil testing.

Maegan Lanham

Students from the local high school participate in water and soil testing.

Stream Team

In addition to recreation, conservationists recognize the importance of investing in the future of rural communities through education. In fact, Ira Yates, the founder of Friends of the Pecos, says it's central to his organization's mission.

Ira Yates is founder of the Friends of the Pecos River.

Ira Yates is founder of the Friends of the Pecos River.

“The other things are big-picture, high-level dreams, but the real pleasure comes in watching the students come out to the river,” he says.

His group's education coordinator, Patina Crowder, worked as a science teacher in Iraan-Sheffield schools for nearly 20 years.

“The way it runs around town and behind the hills, you don't see it, except for a little tiny spot where you cross the river on the highway,” Crowder says. “Since the development of the park, awareness has just skyrocketed.”

Crowder conducts aquatic science activities with students at the Iraan Sheffield School, training them to perform water testing as part of the Texas State University's Texas Stream Team program. Through the program, community scientists learn to monitor water and environmental quality across Texas' waterways. Although the high school students she works with weren't initially interested in the outdoor classroom setting, over time, they've grown more excited about the work as they've recognized its importance as real scientific research.

Crowder's hope is that some of these students will stay in the community and go on to become future leaders, whether in conservation or another field.

“If kids can realize the relevance of the science and its value to a river, then science becomes interesting. It becomes a process that you can apply over any kind of career field, whether its nursing or construction or anything else.”

Crowder, Tamez, Perry and others know the process will take time. Each student, each angler, each bird-watcher and kayaker gives them hope. Piece by piece, through recreation, education and stewardship, this stretch of the Pecos might just move from forgotten to treasured.