Amid a quarter-life crisis in my early 20s, I was looking for a bit of direction when I finished my shift at The Victoria Advocate and sat down in a booth at a local restaurant. I picked up a six-month-old copy of the paper, dated June 10, 2019, which contained a story I wrote on the Texas Water Safari, billed as the world's toughest canoe race.

The idea of doing the Safari sparked something inside me, and after I finished my fried fish I got on Facebook to look for Erin Magee, a veteran solo paddler whom I quoted in the story, and sent her a direct message: “Hi Ms. Magee, do you know where I should start looking to rent or buy a cheap boat to train for the Safari?” She called me later that evening. “If you want to do the Safari, you're going to need a Bugge boat,” she told me.

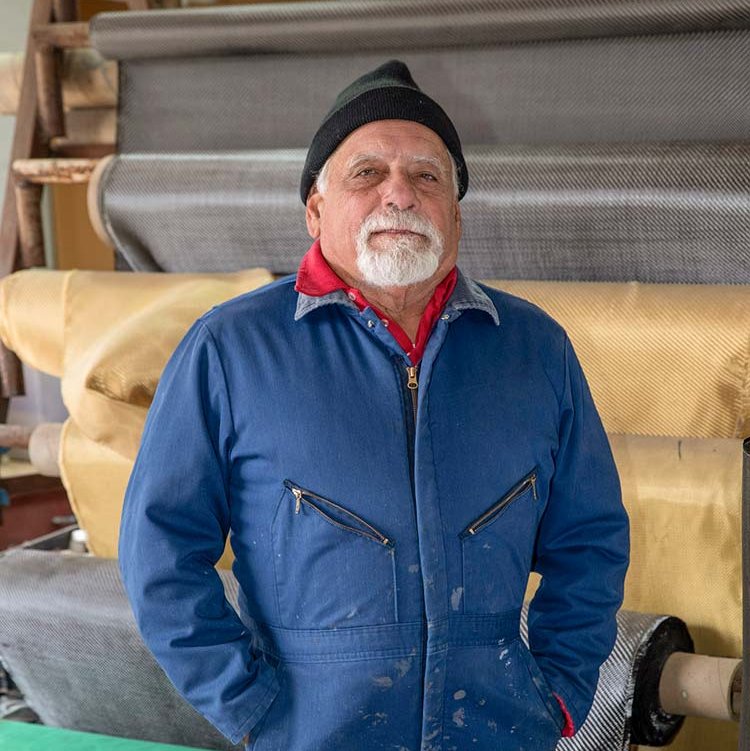

“Boogie?” I asked. “Sounds like fun.” Named for John Bugge, a 45-time Safari finisher who builds rental boats for the race at his workshop in Luling, Bugge boats are known for their durability. Bugge has a reputation for making prospective customers throw boats to the ground and drag them across concrete to prove their hardiness.

I drove out to see him that weekend, and he directed me to an 18-foot-long, sleek and angular boat with enclosed bulkheads on the bow and stern. The “cockpit” contained a seat raised on adjustable metal bars and a rudder with pedals for steering. The matte black color of Kevlar made it look almost tactical.

On its maiden voyage, the boat was like a shark among mackerel as I glided across Lady Bird Lake, swiftly passing graceless kayaks and paddleboards. My friend, paddler Aaron Fides, joined me on that first outing. He dubbed the canoe “the Batmobile,” and the name stuck.

During COVID, I took it out on a socially distanced date or two to impress men with my slick ride. Who needs a Mercedes when you have a 40-pound hunk of carbon, Kevlar and resin? “Nice kayak!” one told me. I couldn't hold back the disdain in my voice as I informed him, “It's a canoe.”

Pride runs deep for those who've been indoctrinated into the cult of the Safari. Since the race began in 1963, countless legends have been told about Safari paddlers, the boats they race and the people who make them. As racers experimented with new designs that would give them a competitive edge, so grew a cottage industry of boat builders along the San Marcos River. They tailored the boats specifically to handle the rocks, rapids, stringers and sweepers of the upper San Marcos River, and a distinct new style of boat emerged: the Safari boat, or, as I like to call it, the Texas Canoe.

Franken-Boats

The Texas Water Safari is, at its heart, an unlimited race, meaning that all teams race for overall position in the 260-mile paddle from San Marcos to Seadrift. Although awards are granted to teams in sub-classes like solo, tandem and aluminum, paddlers in the unlimited class can make their way to the finish line in Seadrift using any boat they please, so long as it is propelled by human muscle power only.

A Safari boat usually has a rudder; the longer your boat, the more you'll need one to navigate narrow gaps between boulders where the current flows. These boats allow paddlers to use either single- or double-blade paddles; most competitive teams carry both, using the nimble single blades in the more technical first 60 miles of the race and switching to double blades as the river gets wider and deeper.

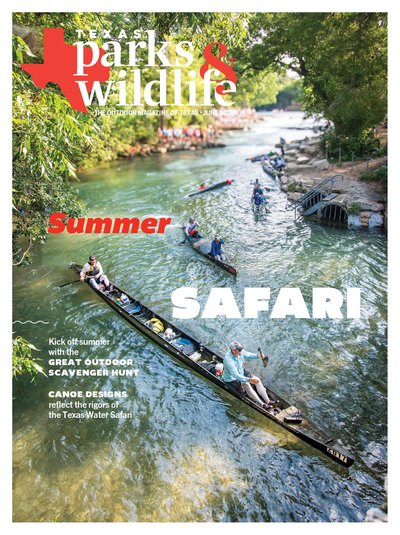

Texas Water Safari competitors set off from Spring Lake in San Marcos.

Texas Water Safari competitors set off from Spring Lake in San Marcos.

Safari team The Cowboys paddle their six-person canoe through a rapid outside Luling.

Erich Schlegel

Safari team The Cowboys paddle their six-person canoe through a rapid outside Luling.

Erich Schlegel

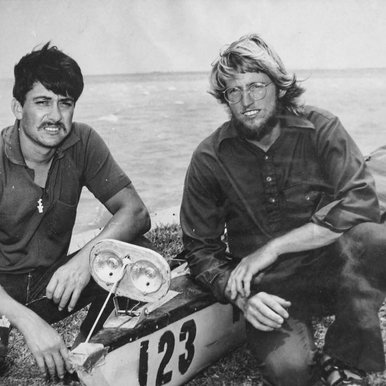

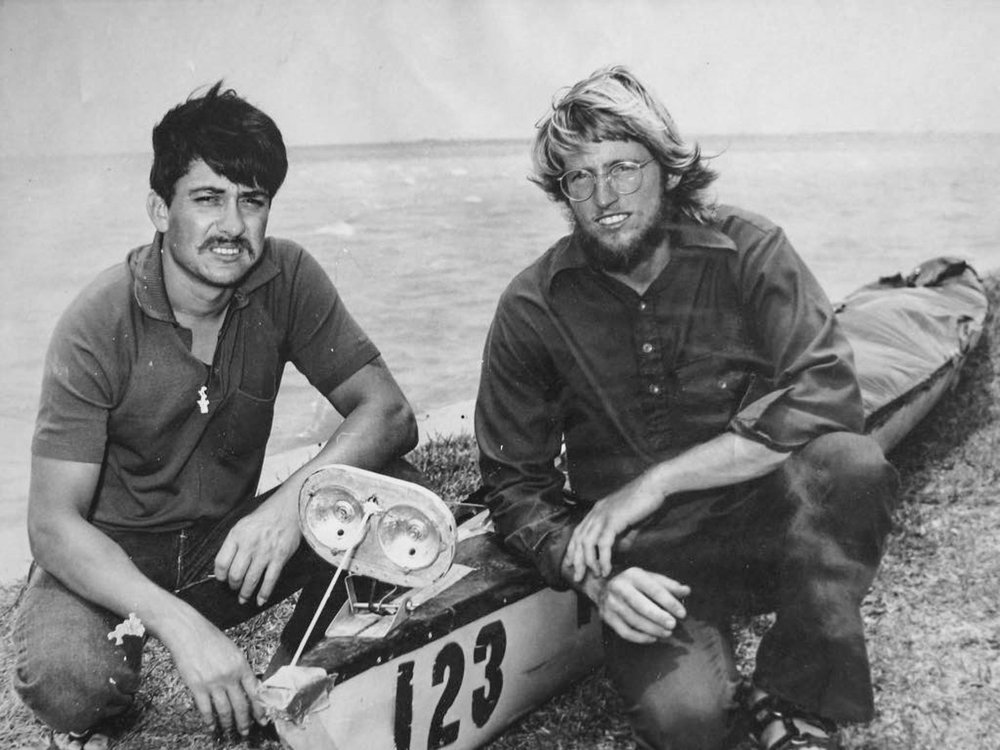

Tom Goynes and Pat Oxshear shook up the Water Safari when they won in a Sawyer Saber.

Courtesy Tom Goynes

Tom Goynes and Pat Oxshear shook up the Water Safari when they won in a Sawyer Saber.

Courtesy Tom Goynes

When Tom Goynes raced his first Safari in 1967, most paddlers were using two-person sculls. They used two oars each and faced upstream, frequently looking over their shoulders to navigate between boulders and around tree stumps. To do so successfully, most scullers had to have good vision. Goynes wore glasses, and he constantly squinted to make out shapes in the periphery.

“To see where I was going, I had to turn around like an owl,” he says.

Sculls dominated the race until 1971, when Goynes and Pat Oxshear won the race in a Sawyer Saber, a 24-foot-long, 30-inch-wide boat manufactured by Michigan-based Sawyer Canoes.

The Saber was the beginning of a Texas boat-building renaissance, in which Safari paddlers decided to throw out the rules like a snake in the boat.

Goynes bought the Shady Grove Campground along the San Marcos River in 1979 and opened a canoe livery on the property, which became ground zero for this golden age. There, he, Oxshear and Jim Trimble designed a three-person canoe by cutting one Sawyer Saber in half and then inserting the middle section of a second Saber. In 1980, they used that boat to become the first three-man team to win. That began a 20-year saga, in which boats grew longer and faster and added more paddlers, culminating in a 50-foot-long, nine-person boat. The Safari's governing board had enough of that tomfoolery by 2006, when they set a cap of six paddlers per boat.

Since the creation of the Saber, racers have all but abandoned row-style boats, with the last Safari-winning scull crossing the finish line in 1979. And, as multiperson boats grew longer, so, too, did solo boats. With the 21 feet of Sawyer Saber left over from the three-person monstrosity, Trimble assembled a solo canoe raced by Peter Derrick in 1980, earning it the moniker the “Derrick Doll.” It was the first long solo boat raced in the Safari, inspiring many such boats to follow.

I'll Know One When I C-1

Around the time Goynes and friends started playing Dr. Frankenstein with canoes, paddling organizations across the country began to standardize boats for competition.

The C-1, a one-person, competition-class canoe, emerged from this era. It's got skinny, tapered ends and signature wide wings at the midpoint. While a C-1 looks much like a kayak, it has a larger volume and rides higher. My Batmobile has a C-1 hull with the unorthodox addition of a rudder and pedals to steer.

The boat's wings provide what's called primary stability, meaning that the boat feels stable, rather than wobbly, when you're paddling in still water. However, the design compromises secondary stability — the ability of a boat to recover from near-tips. If the wing dips below the waterline, there's no coming back. You're going swimming.

Steve Landick, a Midwest paddler, created his own record-shattering solo boat for his first Safari in 1984. The boat bucked convention of the C-1 and instead sported a long and slender design. But that boat was too tippy. He could hardly turn around to keep an eye on the competition — much less keep himself upright many hours into the grueling race. He went back to the drawing board and came up with the Landick II, which is skinny at the front with a wide back end curved like a bowl, providing secondary stability.

The Landick II inspired Mike and Jack Spencer of Martindale to build the Eagle, another long, skinny canoe, and, later, the Extreme and Extreme Pro, which for years were the go-to boats for fast solo paddlers.

More recently, paddlers have started to opt for surf skis — long, narrow, ruddered sit-on-top kayaks designed for speed and riding waves. For years, Safari paddlers wouldn't have dreamed of using this type of boat because it has no room to store food and water. But a 2013 rule change allowed support crews to provide food and water at designated checkpoints and opened new options for racers.

In 2023, two brothers, Tommy and Jonathan Yonley, won the Texas Water Safari in a surf ski, the Stellar Double Elite Low. Although it sacrifices stability, it's specifically designed for paddling in the open ocean, a feature that's made it increasingly desirable to handle the rough bay crossing that comes at the end of the Safari. It's light, too, easing the difficulty of the Safari's infamous portages.

As changing weather patterns make race conditions harder year after year, such boats may become standard for Safari paddlers of the future.

Gaston Jones sands the hull of a C-1 racing canoe; boat builder Jack Spencer's tool bench; Spencer mixes resin to patch a boat; a Landick II gets a coat of epoxy.

Erich Schlegel

Gaston Jones sands the hull of a C-1 racing canoe; boat builder Jack Spencer's tool bench; Spencer mixes resin to patch a boat; a Landick II gets a coat of epoxy.

Erich Schlegel

Gaston Jones sands the hull of a C-1 racing canoe; boat builder Jack Spencer's tool bench; Spencer mixes resin to patch a boat; a Landick II gets a coat of epoxy.

Maegan Lanham

Gaston Jones sands the hull of a C-1 racing canoe; boat builder Jack Spencer's tool bench; Spencer mixes resin to patch a boat; a Landick II gets a coat of epoxy.

Maegan Lanham

Gaston Jones sands the hull of a C-1 racing canoe; boat builder Jack Spencer's tool bench; Spencer mixes resin to patch a boat; a Landick II gets a coat of epoxy.

A Landick II nears the final stages of completion.

Maegan Lanham

A Landick II nears the final stages of completion.

Maegan Lanham

Canoe Craftsmen

At Martindale's Shady Grove Campground, canoes lay scattered across the grass like tombstones, memorials to the Safari's 60-year history. I walked up to the rusted sheet metal warehouse that serves as the headquarters of Spencer Canoes. Inside, I found Jack Spencer stirring a can full of resin and cracking open a Shiner.

“Nobody else makes boats for the Water Safari. It's really a local thing — and not that many people do it,” says Spencer, a five-time Safari finisher who considers himself retired from the world's toughest canoe race. He's one of only a handful of locals, including Bugge, Fred Mynar and Jay Daniel, who carry on the Safari's boat building legacy. “These other makers, they make stuff for the ocean, the lakes; might be stiff, but it's really not made to glide over stones.”

Unlike manufactured canoes and kayaks, Safari boats have been tailored to the specific conditions of Texas rivers. They must endure shallow, rocky waters; collisions with branches and sawed-off tree trunks; even the occasional brush with an alligator or 300-pound gar.

Mike Spencer, Jack's brother, became the first of the two siblings to build his own boat in the mid-1980s. Together, they improved upon their craft and learned the technical and labor-intensive process of creating wood-strip models, making epoxy molds and placing layers upon layers of carbon fiber and Kevlar like papier-mâché. In 1988, the Spencer family bought Goynes' campground and canoe business and have remained an essential part of the Safari community ever since.

When I paid Jack a visit in mid-February, he was in the middle of his busy season as paddlers locked in their plans for the upcoming June race. In his workshop, sitting across half a dozen sawhorses, was a four-person boat. It's one of only about 300 total boats he's made in his lifetime. Bugge has made even fewer, under four dozen, but he's proud of the fact that practically all are still in commission. In fact, he's resurrected a few over the years after they've flown off the back of vehicles barreling down the highway (one was even torn to shreds in a tornado that hit Martindale in 2022).

“There's a lot of caring that goes into making them to where they last as long as most people last,” Bugge says. “I'm not saying that they'll be done at 50 years, but I won't be in them.”

Boat builder and Safari legend John Bugge.

Photo by Maegan Lanham

Boat builder and Safari legend John Bugge.

Photo by Maegan Lanham

Gaston Jones and Jeff Glock work on a racing canoe in Glock's shed.

Erich Schlegel

Gaston Jones and Jeff Glock work on a racing canoe in Glock's shed.

Erich Schlegel

These boats are built to outlive the current generation of Safari paddlers; but what about the next? Some families, like the Mynars of Martindale, have passed down boat building skills to the next generation; there is no clear successor to Spencer or Bugge.

Spencer wants to find and train an apprentice who could someday buy his business. But sometimes he wonders “why bother?” when the Safari's future looks bleak. Flow in the San Marcos River seems to get lower year after year. The longer this trend holds up, the less useful boats become, and the more racers ought to invest in a good pair of hiking boots.

“I'm not sure the San Marcos River is ever really going to recover,” Spencer laments. “I hope the Safari survives it.” But as river flow drops, the number of new Safari paddlers remains strong. In 2019, a record 176 boats started the race at the Meadows Center. Last year, in spite of low water levels, 159 boats started the race. Among that crowd of paddlers, perhaps a future boat builder is waiting to carry the weight of the Safari in their cracked and calloused hands.