Chronic wasting disease tops the list of things that keep Alan Cain up at night.

“I don’t want to see the disease have a significant impact on hunting,” says Cain, White-Tailed Deer Program leader for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD). “CWD is out there on the landscape — we don’t know where it will pop up next. We’re trying to stay on top of CWD as best we can in order to try to limit its impact.”

There’s been a lot of talk in hunting circles about CWD. Across the internet and in chat forums, good and bad information abounds. The deer disease has become the subject of conspiracy theories, and hot debate erupts frequently about the overall spread of the disease and how to mitigate its effects.

Cain says he doesn’t worry so much about how hunting will be affected this season; his concerns are focused on the future.

“Once CWD starts to become more prevalent, you have to worry about impacts not only on deer themselves, but on hunting, hunters and the broader culture at large,” he says. “We need hunters to fund wildlife conservation and to manage the deer populations. We also [want] to maintain the hunting heritage in the state. How will CWD ultimately affect all of that?”

What is CWD?

CWD, or chronic wasting disease, is a malady that affects deer species, including native and exotic species found in Texas. That list includes not only white-tailed deer but also elk, mule deer, sika deer and red deer.

An infected animal slowly develops a host of clinical signs, which include listlessness, stumbling, increased drinking and urination, and progressive weight loss or wasting (hence the name).

Because of the neurological damage caused by the disease, infected animals lose the ability to care for themselves and, with enough time, will ultimately die from the disease.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention classifies it as a prion disease. According to the CDC, prion diseases (also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies or TSEs) are a “family of rare progressive neurodegenerative disorders that affect both humans and animals.”

To understand prion diseases, you need to start from the beginning. The word “prion” is an amalgamation of the words “protein” and “infection”

and comes from the longer form “proteinaceous infectious particle.”

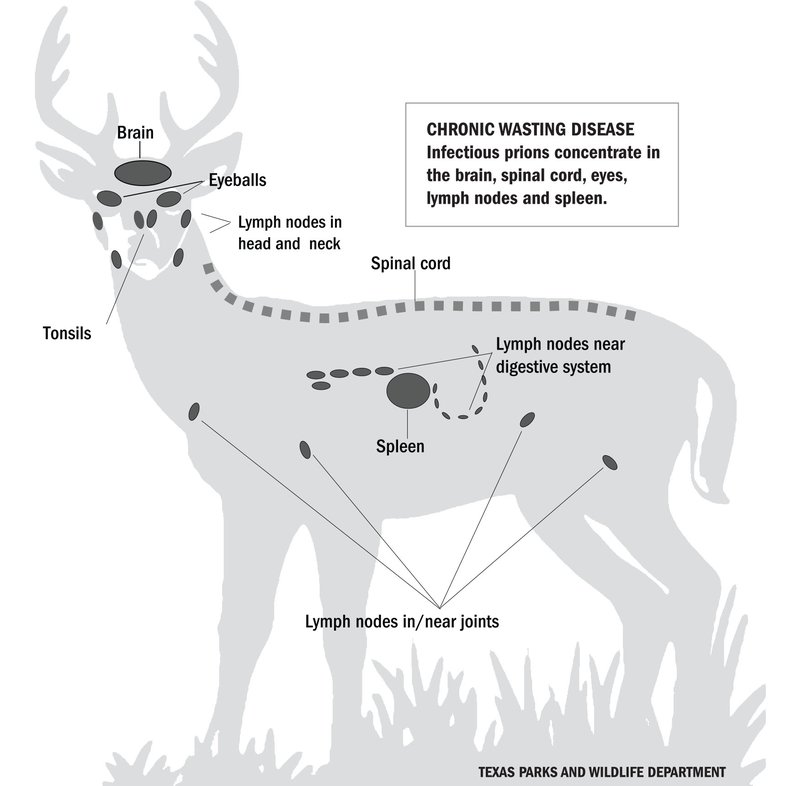

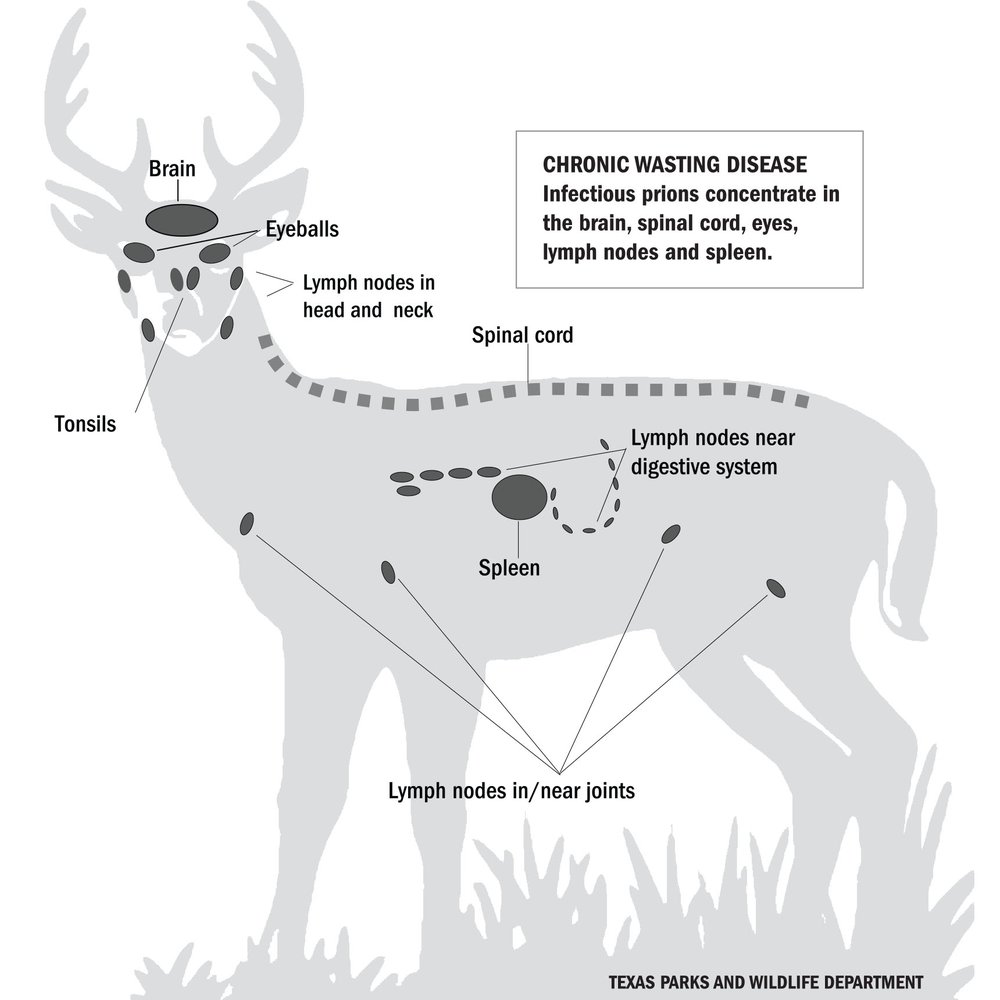

CWD affects certain types of proteins (prions) commonly found in the brain, causing them to "fold" abnormally.

The clinical signs of the resulting brain damage slowly materialize in the host animals. That’s what makes this disease difficult to catch in its early stages.

The prions can propagate and transmit their misfolded configurations to other proteins. Unlike a bacteria or virus, proteins are transmitted at the molecular level.

Furthermore, because prions are highly resistant to degradation, they can last for a long time in the soil, water or other affected surfaces (such as brush or forage). CWD also spreads between animals through contact with contaminated body fluids and tissue.

“It’s always fatal once an animal develops the disease,” says David Hewitt of Texas A&M University-Kingsville, a nationally recognized CWD expert. “There’s never been an animal that’s recovered.”

Since it can take over a year for an infected animal to show clinical signs, it can be difficult to find and respond to CWD.

“It’s not like anthrax or blue tongue or some of those diseases where you find a bunch of dead deer, and it’s obvious what the answer is,” Hewitt says. “With those types of diseases, getting mobilized and getting something done is easy. With CWD, it’s playing out over decades. Since there’s no obvious daily impact, it’s slowly gaining a foothold in deer populations.”

The effects on deer herds can be devastating. Western states, where CWD was first discovered, have seen some significant declines in their deer populations.

Like Cain, Hewitt’s also concerned about the impact on the state’s hunting heritage and the value for those who take pride in harvesting their own venison for the table.

“If CWD takes away the food value of wildlife and from hunting, it’s going to have an impact,” he says. “If nothing else, just the hassle of harvesting an animal, getting it tested and finding out it’s positive, and then having to dispose of the meat after you’ve gone through all that effort will have a negative impact on hunting.”

Tainted meat?

PRION DISEASES include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or mad cow disease), and the sheep and goat disease scrapie. Some prion diseases can spread to humans who consume the meat of the infected animal.

There have been no reported cases of CWD infection in people. The CDC says that some animal studies suggest CWD poses a risk to certain types of non-human primates, like monkeys, that eat meat from CWD-infected animals or come in contact with brain or body fluids from infected deer or elk.

These studies raise concerns that there may also be a risk to people. Since 1997, the World Health Organization has recommended that it is important to keep the agents of all known prion diseases from entering the human food chain.

Dr. Hunter Reed, a TPWD veterinarian, says it’s best to operate (at least for now) with some level of concern.

“Since the jury is still out on the zoonotic aspect of CWD, most agencies operate out of an abundance of caution,” he says. “If you test your harvest and get a positive result back, it is recommended not to consume it. We still don't have concrete evidence that suggests CWD has potential to cross over into humans. It hasn't happened so far. We just want to be careful.”

A History of Infection

WHILE THE BEGINNING of chronic wasting disease is hard to ascertain, patient zero was first discovered in a government-run captive mule deer research herd in northern Colorado in 1967. While initially classified correctly as a wasting disease, CWD later received a more specific diagnosis as a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy disease.

In 1981, CWD was first discovered in the wild. In the ensuing 40 years, the disease has spread slowly throughout the country. As of August 2023, it’s been recorded in 31 states and four Canadian provinces. CWD has been discovered in moose in the Nordic countries of Finland, Sweden and Norway, as well as in a small number of cases in South Korea.

Some scientists believe that that CWD may be more widespread, but due to the slow progression of the disease and lack of standardized surveillance processes, it can be difficult to detect.

Texas Cases

THE FIRST CWD-positive result in Texas was discovered in a free-ranging mule deer herd located in the Hueco Mountains of far West Texas in 2012. In 2015, the first white-tailed deer tested positive for CWD in a captive breeding facility in Medina County during routine disease monitoring.

Since then, the department has documented more than 500 CWD-infected animals throughout the state. Of those, around 100, about 20 percent of the infected animals, are free ranging. The other 80 percent come from breeder deer or breeder release sites. Breeder deer are raised under controlled conditions and behind high fences to typically influence the animal’s phenotype for large antlers.

Deer breeders are under more robust CWD surveillance requirements due to the greater transmission risks associated with these operations. More than 50 CWD-positive results have occurred in 10 breeding facilities so far this year.

“From what we’ve seen in the Trans-Pecos and Panhandle, where you have truly free-ranging CWD-positive deer, the disease really hasn’t expanded in range too much,” Reed says. “But in the other parts of the state where we’ve seen recent detections [Hunt, Kaufman and Kimble counties], those free-ranging positives are all in relation to captive breeding facilities that had positive detections and those who received deer from those captive facilities.”

Reed says there are puzzling instances, such as a May positive test result in Bexar County, where the disease’s origin can’t yet be determined.

The Game Plan

TO MITIGATE the effects of CWD, TPWD has instituted mandatory testing and carcass movement restrictions in zones where CWD has been detected and has launched a robust educational campaign that increases awareness of the disease for hunters and the general public. While there’s little hope for eradicating CWD, much can be done to limit the further spread of the disease.

“Right now, we’re finding CWD in more and more areas,” says Ryan Schoeneberg with TPWD’s Big Game Program. “We have to be aggressive in our actions and reactions to the disease.”

Schoeneberg points out that while only 500 positive results in a state with more than 5 million wild deer can seem insignificant, it’s not.

“We don’t want to be like some states that have it so bad that it’s a flip of the coin as to whether a harvested deer tests positive for CWD or not,” Schoeneberg warns. “We want to develop strategies that will help us slow the spread of the disease until the science catches up.”

To that end, the agency has been working with interested stakeholders through the state’s Chronic Wasting Disease Management Plan. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission adopted one of the first monitoring zones and carcass movement restrictions in August 2016 following detections of CWD.

Since then, as new cases of CWD were discovered, TPWD has required further mandatory testing and restrictions on live deer and carcass movements with additional containment and surveillance zones.

In 2023 alone, TPWD has established 10 new CWD surveillance zones following detections in captive breeding facilities in addition to a containment and surveillance zone for Bexar County following a CWD detection in a free-ranging deer.

Hunters who harvest deer or other susceptible species in those zones are required to bring their animal to a check station within 48 hours. When a CWD case is found in a captive herd, TPWD will work with the owner to create a herd plan that mitigates the risk of transmission.

Regardless of a detection in a captive or free-ranging context, further education and outreach will be key to mitigating the future spread of CWD.

“One of the key things we have to do is talk to people everywhere,” says Cain. “There’s a lack of awareness about the disease. People may have heard of CWD, but they really don’t know much about it. We want to educate the public about what the disease is and how serious it is. We also want people to know that we’re a credible source of information.”

TPWD and its partners will continue to work together to advance the science regarding CWD and contain the disease from further spread.