Should roasted minnows, grilled cranes and charred beefsteak replace turkey and dressing on our Thanksgiving tables?

Four centuries ago, a ragtag group of European settlers who barely escaped starvation celebrated their survival with a feast of gratitude to God, gathering with Indigenous inhabitants to share the bounty of the land. The story might sound familiar, but this was 1598, not 1621— and they were feasting on the banks of the Rio Grande, not Massachusetts Bay.

Many scholars believe that America’s actual first Thanksgiving took place near San Elizario, Texas, on April 30, 1598. “It was a party,” says Kimberly Sumano-Ortega, a historian at the University of Texas at El Paso. Ortega specializes in El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (the Royal Road of the Interior), the major Spanish thoroughfare that connected Mexico City and Santa Fe, N.M., for 300 years.

The route was just a patchwork of Native American trails in January 1598, when Captain Don Juan de Oñate set off traveling north from Santa Barbara in southern Chihuahua. A few conquistadors had made the journey before, but nothing like Oñate’s expedition: 400 men (130 with their wives and children), 83 ox-drawn wagons, and a massive herd of 7,000 livestock that stretched three miles long and three miles wide. They weren’t exploring, they were colonizing — and their destination was 700 miles away in San Juan Pueblo, 20 miles north of today’s Santa Fe.

By early March, they entered the unforgiving wilds of the Chihuahuan Desert. The expedition’s historian, Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá, later wrote about the ordeal. “We journeyed on and on until it seemed that we would never find our way out of these unpeopled regions, traversing vast and solitary plains … we suffered terribly from the burning sands.” Thorny thickets ripped their clothing, and their shoes slowly wore away. When food supplies gave out, they were forced to scavenge for edible roots and weeds. After six weeks in the desert, their water ran out, too. They plodded on for four days, man and beast alike slowly going mad with thirst. Many didn’t make it.

But on the fifth day, salvation appeared: the Rio Grande. “The gaunt horses approached the rolling stream and plunged headlong into it,” writes Villagrá. “Our men, consumed by the burning thirst, their tongues swollen and their throats parched, threw themselves into the water.” They camped near present-day San Elizario, just east of El Paso, “the Elysian fields of happiness,” he adds. “Joyfully we tarried ‘neath the pleasant shade of the wide spreading trees which grew along the riverbanks … where [we could] rest our tired, aching bodies.”

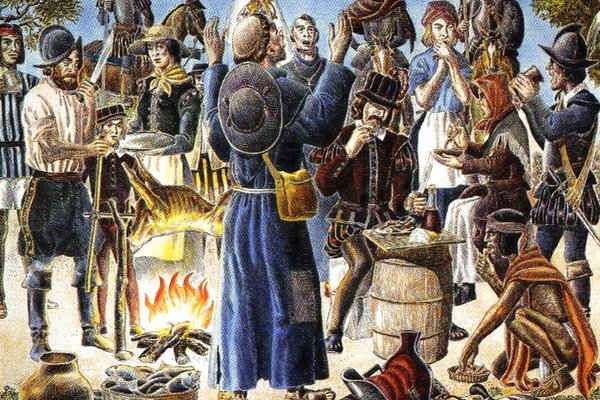

Ten days later, on April 30, the beleaguered colonists had recovered. Now it was time to celebrate. Villagrá recalls the day: “We built a great bonfire and roasted the meat and fish, and then all sat down to a repast the like of which we had never enjoyed before.” They would have certainly butchered cattle from the herd, cooking quarters of beef over open flames and coals — carne asada. Offal likely went into soups like menudo, and bones were boiled for broth. They may have also slaughtered sheep, goats or pigs, animals commonly brought on Spanish expeditions.

For fish, the Rio Grande provided all they could eat. Villagrá relates how local Indigenous people helped with the feast: “Four Indians guided them to the river and brought back a great quantity of freshly caught fish, a gesture of peace and friendship.” In 1598, the river supported an abundant variety of aquatic life, likely catfish along with silvery minnows, red shiners and longnose gar. The people Villagrá encountered were the Manso, a peaceful, semi-settled people who welcomed the hungry strangers. “Manso were very similar to Pueblo people,” says Ortega. “They would have pit houses with fire pits inside.”

What other foods from the fertile river valley might have appeared on the Thanksgiving table? Waterfowl were plentiful in the area; an earlier explorer had noted that the Manso ate cranes, ducks and geese. Primarily foragers, the Manso ate “whatever was available,” Ortega says. “I mean anything. Turtles, cactus, deer, rabbit and probably snakes.” But they also cultivated corn, beans and squash in tiny fields along the river, she adds. It’s also possible that our favorite Thanksgiving poultry made an appearance. “The Manso would have been raising turkeys, and [the Europeans] would have taken them.”

Villagrá’s “peace and friendship” impression is quite plausible. “Indigenous people are very supportive, and first encounters were usually kind,” says Ortega. The Spanish were just passing through, after all, and the Manso were happy to help them on their way. “They all knew it was going to be a very fast encounter. So if it was a temporary party, why not enjoy it? Let’s have fun — and then we’ll stay, and you keep on going.”

And they did have fun. First, the day began with Oñate planting a cross by the water and formally claiming “all the kingdoms” of New Mexico for Spain. “The Captain … held thanksgiving Mass, gave thanks for safe passage, and celebrated,” writes Villagrá. According to the official military report, “There was a sermon, great religious and secular solemnity, a ceremonial [gun] salute and much rejoicing, and in the afternoon, a comedy.” A comedy? Villagrá says the play dramatized the “great reception” given to the Spanish Franciscans by the Native people. “It was like a model to show the Indigenous how to behave,” explains Ortega. Villagrá also recounts “pleasing festivals; splendid men on horseback … a gallant squadron.” Music and dancing almost certainly ensued.

It was a day of feasting and friendship, and for the Spanish, more proof that God was guiding them. The expedition soon continued on into New Mexico’s mountains, officially establishing the Camino Real and opening the American Southwest for colonization. Four centuries later, the Texas Legislature recognized the 1598 celebration as the First Thanksgiving in America (Massachusetts declined to respond).

So if you’re craving steak and catfish this Thanksgiving, or carne asada and menudo, go ahead — you’re in good historical company. Light a bonfire and put on a comedic play. And keep the turkey and dressing, too (and certainly the pumpkin pie). In the great state of Texas, we have room for all kinds of foods and all kinds of people at our cherished Thanksgiving table. We’ll save you a seat.