"IF I HANDED YOU THE OLDEST KNOWN BOOK in North America, what would you do with it?” Asks Carolyn Boyd, the foremost expert on the rock art of the Lower Pecos canyonlands and an anthropology professor. Sitting in her Texas State University office, she explains that these “books” are Pecos River-style pictographs painted on limestone canvases thousands of years ago by nomadic hunter-gatherers.

“These are the first books written in North America,” says Boyd. “You would want to treat them reverently, preserve them and know what they say, what information they hold. The information in these ancient manuscripts is part of the human story. What we are learning from them is truly rewriting the history of our continent.”

Boyd and her colleagues at the Shumla Archaeological Research and Education Center in Comstock have upended long-held beliefs that the visual narratives of Lower Pecos rock imagery are incomprehensible.

Founded by Boyd in 1998, Shumla is dedicated to documenting, protecting and raising awareness of Lower Pecos rock art through research, preservation and education. In recent years, the Shumla team, including Boyd and science director Karen Steelman, has unlocked the secrets of Pecos River rock art using advanced technologies such as high-resolution GigaPan photography, digital microscopy, X-ray fluorescence and 3-D modelling.

Steelman has dated Pecos River murals up to 5,500 years old — older than Egypt’s first pyramids. Radiocarbon dating techniques perfected at Shumla have revealed that Pecos River-style rock art was produced continuously for more than 4,000 years.

“These are the oldest securely dated pictographs and the longest enduring art tradition with complex narratives in the Americas,” says Boyd.

Boyd changed the course of Lower Pecos rock art and Mesoamerican research by cracking the code of the Pecos River pictographs. She was the first to identify striking parallels between Pecos River-style art and other Native American iconography, including the visual narratives of surviving Aztec codices and the iconography and sacred stories of contemporary Huichols, an Indigenous people of central-northwest Mexico.

“It’s mind-blowing that living Indigenous people today can read thousands-of-years-old rock art,” says Boyd, recalling the time she brought a Huichol shaman to the White Shaman site. “When he saw the mural, he wept and said, ‘They are all here, all of my ancestors, all of my grandfathers.’

“We look at the murals as just two-dimensional pictures, but that’s not the way Indigenous people look at these images,” she adds. “They are living, breathing and sentient. The paintings weren’t produced so much for you to see as it was for those spirits to look out on creation — and to look upon you.”

Boyd’s journey from muralist and painter to archeologist began in 1989 when she visited the Lower Pecos and saw the White Shaman mural. “It immediately spoke to me as being a well-planned composition created by an individual, not a random collection of images,” she recalls. “I knew I was looking at a masterpiece that was thousands of years old.”

Seeing the White Shaman was her Rosetta Stone experience, opening a path to understanding the belief systems and cosmology of the people of the Pecos.

I, too, am eager to see the White Shaman mural. It’s the centerpiece of the White Shaman Preserve, managed by the Witte Museum in San Antonio, which offers public tours during the fall, winter and spring. Another must-see site is the Fate Bell rock shelter, also accessible by public tours, at nearby Seminole Canyon State Park and Historic Site.

Seminole Canyon: The Hidden Gem

DRIVING WEST of Del Rio along U.S. Highway 90, I roll past drought-depleted Amistad Reservoir and enter the Lower Pecos canyonlands. Though harsh and arid, this land sustains diverse life and conceals a painted landscape. More than 350 known pictograph sites lie within a 60-mile radius of the confluence of the Pecos River and Rio Grande.

Hundreds of archeological sites were inundated by Amistad Reservoir in the late 1960s, and most of the surviving murals lie on private land. Today, Shumla, the Witte Museum, Texas State University, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, the National Park Service and private landowners collaborate to protect the rock art, still threatened by erosion, humidity, floods and vandalism. The cultural resources of the Lower Pecos Archaeological District are so significant, the region was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2021.

“There’s no other area in North America and Mesoamerica with such an incredible, intense concentration of pictographic rock art,” says Harry Shafer, a 60-year veteran of Lower Pecos archeology. “It’s the nature of the landscape — there are canyons upon canyons with protected canvases they could paint on.”

Seminole Canyon State Park and Historic Site, 40 miles northwest of Del Rio, is a sanctuary for rock art lovers. “This park is a hidden gem. Most people stumble upon it on their way to Big Bend,” says Superintendent Craig Howell.

The park packs a lot of rock art viewing and adventure opportunities into 2,172 acres. The Fate Bell rock shelter, named for the first Anglo landowner Fayette “Fate” Bell, is the Louvre of the Lower Pecos. More than 500 feet wide, the cavernous shelter harbors a remarkable array of pictographs.

Seminole Canyon's Fate Bell rock shelter has protected and preserved ancient rock imagery.

Maegan Lanham

Seminole Canyon's Fate Bell rock shelter has protected and preserved ancient rock imagery.

Maegan Lanham

Seminole Canyon pictographs.

Maegan Lanham

Seminole Canyon pictographs.

Maegan Lanham

I join volunteer guide Lance Hildreth for a 10 a.m. tour into Seminole Canyon. As we descend 250 feet along a steep trail to the canyon floor, Hildreth points out the abundant lechuguilla, sotol, yucca and other useful plants that sustained the people of the Pecos for millennia.

Entering the Fate Bell Annex rock shelter, we see our first pictographs in the Pecos River style, one of the oldest of the region's five rock art styles, and the most elaborate. Other styles include Red Linear, Bold Line Geometric, Red Monochrome and Historic. Painted in polychrome hues of black, red, yellow and white, Pecos River-style images include human-like anthropomorphs, animal-like zoomorphs and enigmatic figures that pique our imaginations.

We climb to the Fate Bell rock shelter. Deep bedrock mortars and limestone rubble from earth ovens are tangible signs of long-term human habitation. Rock piles and shallow pits from an era when Fate Bell was a pay-to-dig site for relic hunting scar the shelter floor. Fortunately, swaths of rock art remain mostly unscathed. The highlight is a vivid Pecos River tableau: a winged, antlered deity encircled by smaller figures in a counterclockwise procession. To my modern eyes, the elongated, rectangular anthropomorphs, with stubby legs and outstretched arms, have both an abstract and numinous allure.

“This rock art panel is really the best of the best,” says Hildreth. “These beautiful pictographs represent a belief system of an ancient people. When you hear the term hunter-gatherer, it evokes a very simple and primitive people. If you spend time looking at their pictographs, you realize they were complex, deep thinkers. They were very amazing people.”

In the Presence of the White Shaman

Hikers climb steps to the White Shaman alcove.

Aimee Spana | The Witte

Hikers climb steps to the White Shaman alcove.

Aimee Spana | The Witte

A group trek led by Aimee Spana brings curious viewers to see the White Shaman mural.

Aimee Spana / TheWitte

A group trek led by Aimee Spana brings curious viewers to see the White Shaman mural.

Aimee Spana / TheWitte

The White Shaman mural is tucked away in an alcove-like rock shelter perched high on a cliff in a side canyon overlooking the Pecos River. Much smaller and more intimate than Fate Bell, this was a sacred ceremonial site rather than a habitation.

Despite its fame today, the White Shaman wasn’t documented until 1958. San Antonio photographer Jim Zintgraff helped preserve the White Shaman and coined its evocative name. He and archeologist Solveig Turpin co-founded the Rock Art Foundation in 1991 to protect Lower Pecos rock art sites, especially the White Shaman. In 2017, the foundation transferred the White Shaman Preserve to the Witte Museum.

I join an early-morning tour group, led by Aimee Spana, director of the White Shaman Preserve, and we caravan into the 400-acre preserve.

Spana shows us samples of crushed minerals the ancient ones may have used to create the paint – manganese for black, hematite-rich ochre for red, limonite for yellow and gypsum for white.

“All the minerals are locally sourced in this region,” says Spana. The ancient artists added water and animal fat from deer and other animals. Because oil and water don’t mix well, the paint makers also added yucca juice, a soapy, sudsy emulsifier, producing a durable, natural oil paint.

Creating paint for hundreds of murals was a communal sacrifice. The use of calorie-rich animal fat, a precious dietary resource in this harsh environment, underscored how important the murals were to these ancient peoples. Mural making required another communal effort: The artists constructed ladders and scaffolds from plant materials such as sotol stalks to paint figures high up on shelter walls and ceilings.

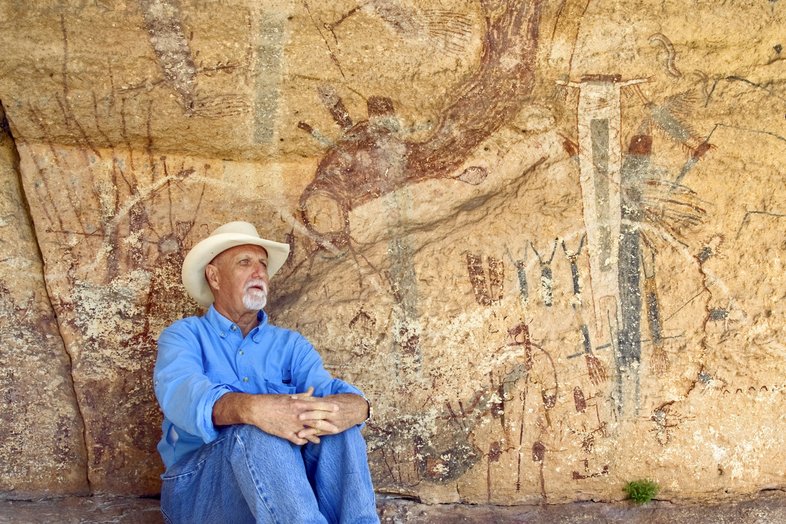

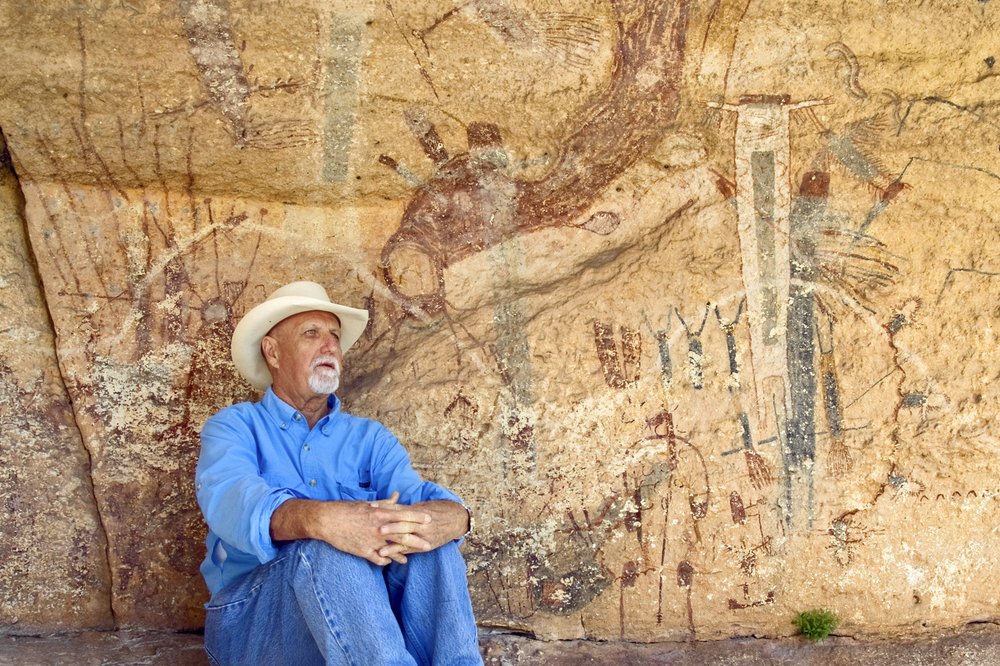

Harry Shafer is a 60-year veteran of Lower Pecos archeology.

Aimee Spana / TheWitte

Harry Shafer is a 60-year veteran of Lower Pecos archeology.

Aimee Spana / TheWitte

Using digital microscopy to study paint layers, Shumla researchers discovered that the painters applied the colors in a specific order. First came black (associated with primordial darkness before creation), then red (the horizon’s fiery hue before sunrise), then yellow (the birth of the sun) and finally white (sunlight at the brightest time of the day). These four colors of the palette were used over and over in Pecos River-style murals in that deliberate, painstaking order for thousands of years.

The trail winds along flat upland terrain, past earth ovens and through thickets of thorny, desert-adapted plants. We reach the edge of the canyon and begin our descent, zigzagging down a steep trail that drops the equivalent of 100 flights of stairs. To reach the White Shaman, we clamber up limestone steps, holding onto iron chains as we ascend.

“The White Shaman is a sacred space,” says Spana as we enter the alcove. “It’s like walking into someone’s church. Please spend the first few minutes in silence and pay homage to the ancestors who painted it.”

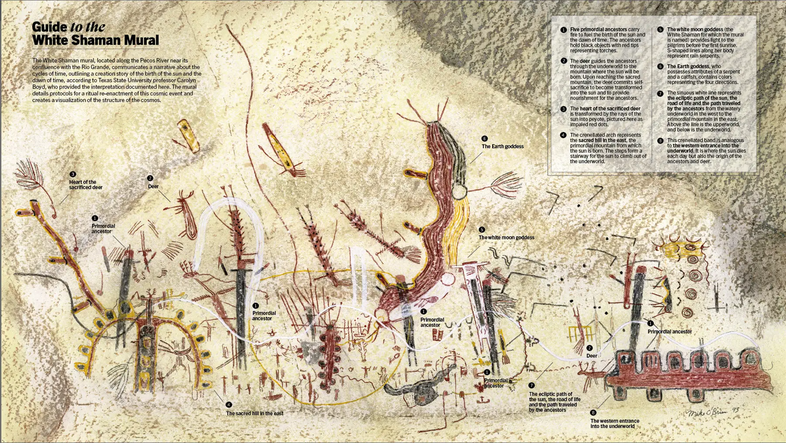

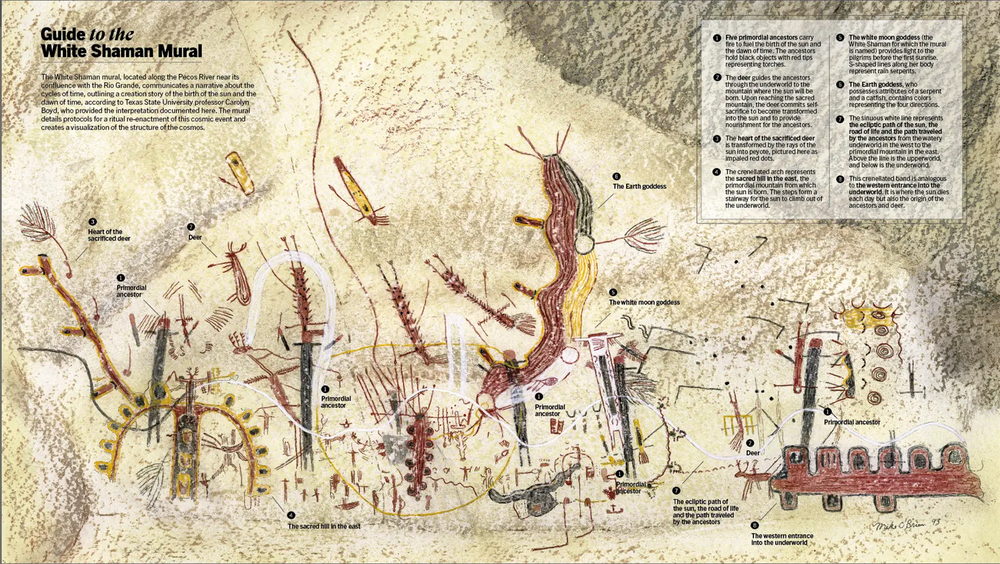

The White Shaman, a deity and not a shaman at all, faces west, catching the sun’s last rays. While small (26 feet long and 13 feet high), the mural is infinitely complex, comprising six zoomorphs, 69 enigmatic figures and 42 anthropomorphs, some antlered, some headless and some impaled with darts and spears.

TPWD

TPWD

It’s a creation story. Spana explains: “This composition is an interwoven narrative depicting the beginning of time, the birth of the sun, and the cosmology of the people of the Pecos.”

While some rock art enthusiasts prefer to “let the mystery be,” believing the murals are unreadable, Carolyn Boyd thinks otherwise. In her seminal book, The White Shaman Mural, she explains White Shaman iconography as an ancient precursor to the beliefs systems of Mesoamerica civilizations and the contemporary Huichol. “Prehistoric art is not beyond explanation,” she also observes in her first book, Rock Art of the Lower Pecos. “Images from the past contain a vast corpus of data … that can enrich our understanding of human lifeways in prehistory.”

I linger in the alcove while the tour group descends into the canyon. Removing my lens of logic and science, I gaze at the faceless figures and deities, and they look back at me, for all the world to see.