Kristin Dyer took deep breaths through her respirator as she picked her way down the rocky slope into Bracken Cave. If it weren’t for the heavy-duty mask covering her eyes, mouth and nose, Dyer would be overwhelmed by the toxic stew of ammonia from guano produced by millions of bats. As she and other researchers entered Bracken Cave in early October 2025, they wore several other pieces of protective gear: hiking boots, thick, long pants and nitrile gloves.

“Just the walk down to the cave is pretty treacherous,” Dyer says. “There’s a bunch of large stones that you could twist your ankle on. Every time you go down, you get cacti stuck in your legs. There are thistles, snakes, skunks and raccoons.”

Dyer, a Ph.D. student in the Becker Lab at the University of Oklahoma, planned this dirty job with the goal of attaching tiny devices to the backs of a few Mexican free-tailed bats living in this Central Texas cave, the world’s largest bat colony. These devices will help them track the bats’ movements and see if there’s any connection between the 15 million bats at Bracken and those at Selman Cave, a cave in northwestern Oklahoma that houses the Becker Lab’s primary research colony.

The devices may also help solve some of the last great mysteries of mammal migration — where these bats migrate in Mexico and how they get there. To help solve these mysteries, Dyer and other researchers have turned to an emerging network of tracking technologies called Motus. Thanks to Motus’ growing network of receiver towers, researchers can gather data from signals sent by tiny, network-compatible transmitters like the ones Dyer attached to bats at Bracken.

Not only is this network unlocking new data about bat movement, it’s also providing vital data on the movements of other small migrating creatures like birds and even monarchs. The automated radio telemetry stations form an invisible web that captures the movements of these flying creatures, revealing migration secrets that have eluded scientists for generations.

Texas, positioned along the Central Flyway and bordering the Gulf of Mexico, occupies a critical position in North American migration routes. Each spring and fall, billions of birds, bats and insects funnel through the state, making it essential territory for understanding continental migration patterns. The deployment of Motus stations across Texas began in earnest within the past few years, and the network has been growing since then as researchers recognize its potential.

Researchers use nets and small cotton bags to grab bats and bring them out of a cave near Childress to tag them.

Maegan Lanham

Researchers use nets and small cotton bags to grab bats and bring them out of a cave near Childress to tag them.

Maegan Lanham

A bat with a Motus transmitter.

Krysta Demere

A bat with a Motus transmitter.

Krysta Demere

Bats fly out of a cave for their evening feed.

Maegan Lanham

Bats fly out of a cave for their evening feed.

Maegan Lanham

A Growing Network

Motus, named for the Latin word for movement, is an international research community organized under the nonprofit Birds Canada. In the decade-plus since the Motus Wildlife Tracking System launched in 2014, the platform has emerged as a leader in global wildlife tracking. It grows stronger and more informative as new stations join its global network of stationary, inexpensive radio receivers that can pick up signals from any animals tagged with compatible tracking transmitters. So far, the network includes more than 2,150 active stations in 34 countries, primarily North America.

Establishing a viable, informative network of receivers is mostly a numbers game; receivers in the Motus network can pick up signals only from animals that pass within a roughly 10-mile range. That means there are still gaps, especially in places like Texas, where there are 67 stations spread over around 268,500 square miles.

In recent years, the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory has established 15 towers on the Texas coast from High Island, near the Louisiana border, south to Rockport in hopes of creating a virtual radio telemetry zone along the coast that migrating birds will fly through on their way north and south.

“In the last three years since I first really started to pay attention to this, our coverage map has changed pretty substantially,” says Tania Homayoun, ornithologist at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

A Motus tracking station in the Sierra Diablo Wildlife Management Area.

Maegan Lanham

A Motus tracking station in the Sierra Diablo Wildlife Management Area.

Maegan Lanham

To begin filling in the gaps, TPWD in 2024 began to install its own stations as part of the Texas Motus Project, a collaboration between TPWD, Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, American Bird Conservancy, Bat Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy, Dixon Water Foundation and other organizations. So far, this project has yielded a collection of 18 Motus stations, mostly at state parks and wildlife management areas.

As part of the project, Homayoun oversaw the installation of four Motus stations in East Texas in 2025 in collaboration with American Bird Conservancy.

In addition to the four Homayoun installed in East Texas, 13 stations have been installed in West Texas and the Panhandle as part of a partnership between TPWD and Bird Conservancy of the Rockies to track grassland birds.

Grassland birds are some of the most endangered birds in North America. Their populations have declined dramatically over the past several decades — more steeply than almost any other group of North American birds.

“West Texas is an important corridor for migratory grassland birds,” says Krysta Demere, a regional biologist for TPWD who oversaw the West Texas Motus collaboration. “This is a way for us to kind of gain a broader understanding of what birds are doing during the winter and where our wintering birds are actually going during the breeding season.”

Texas Motus Project's Fab Four

Conservation actions that protect the Fab Four grassland birds also benefit other species.

Baird’s sparrow

Andrew | StockAdobe.com

Baird’s sparrow

Andrew | StockAdobe.com

Chestnut-collared longspur

Rachel Dolokoffopper | StockAdobe.com

Chestnut-collared longspur

Rachel Dolokoffopper | StockAdobe.com

Sprague’s pipit

McGowan Macaulay Library

Sprague’s pipit

McGowan Macaulay Library

Thick-billed longspur

John Carlson | USFWS

Thick-billed longspur

John Carlson | USFWS

The Texas Motus Project is concentrating mostly on tracking migratory species that are listed as species of greatest conservation need. This list includes grassland birds known as the Fab Four: Baird’s sparrows, whose clear, tinkling song is one of the defining sounds of the Great Plains; Sprague’s pipits, which deliver their waterfall-like song while flying high in the sky; thick-billed longspurs, which reside in the shortgrass prairies at the center of the North American continent; and chestnut-collared longspurs, which sport a striking facial pattern of black, white and buff framed by a rich chestnut nape.

“All of these birds have important wintering grounds in West Texas that we just don’t know a lot about,” Demere says, adding that she hopes Motus will provide some answers.

Although a bird-focused conservation group helped install the West Texas stations, Demere says the Motus towers will also benefit other species and conservation groups.

Researchers such as the Becker Lab in Oklahoma have already used the Texas Motus Project to track movements of Mexican free-tailed bats.

Established in September 2024, the Motus station at Big Bend’s Black Gap Wildlife Management Area has detected three Mexican free-tailed bats tagged in Oklahoma’s Selman Cave, two Sprague’s pipits tagged in Montana, a Wilson’s phalarope tagged in California and, in October 2025, a bat tagged at Bracken Cave — a continental convergence of species that might have otherwise gone unnoticed.

In addition, TPWD bat biologist Samantha Leivers and Bat Conservation International have placed 225 radio transmitters on cave myotis, a "mouse-eared" species of bat that can be found in cave colonies in places like Old Tunnel State Park.

Leivers is using Motus to learn more about how the cave myotis is being affected by white-nose syndrome, a devastating fungal disease striking bats across the country.

“We still don't know a lot about where that bat migrates to and from,” Leivers says. “This effort is hopefully going to provide Texas Parks and Wildlife with more information on how we can monitor this species, especially in the wake of this fungal disease.”

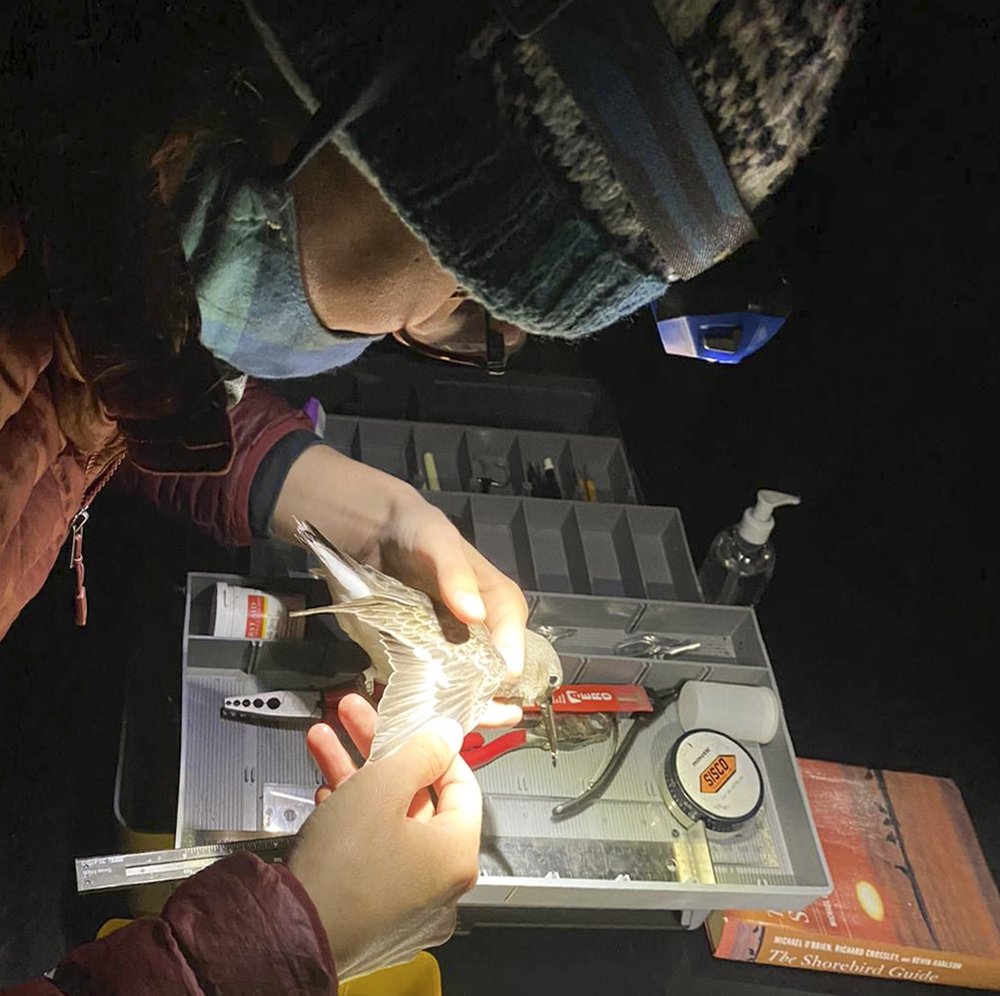

A researcher attaches a tracker and collects data.

Yoursif Attia Motus

A researcher attaches a tracker and collects data.

Yoursif Attia Motus

Tiny Trackers

The first instances of remote animal tracking technology go back to the 1950s, when scientists built radio transmitters small enough to be attached to rabbits, and then later birds. The technology was limited by both the size of animal it could track and the range. If you’ve ever driven far enough for your favorite radio station to slowly turn to static, than you understand the limited range of radio waves. To track the movement of an animal, scientists would have to follow the animal along its route to stay in range. In one early use of this technology, in 1965, a researcher followed a transmitter-equipped gray-cheeked thrush by following behind it in a plane for over 400 miles.

Over the last half century, technological innovations have made tracking technology smaller and more efficient. Some radio transmitters used today, including the smallest Motus tags, weigh as little as 0.15 grams. To put that into perspective, a dollar bill, a paper clip and a single spaghetti noodle all weigh about one gram.

Daniel Becker, a professor at the University of Oklahoma who leads the lab where Dyer works, says these innovations have made it possible to study small creatures like the Mexican free-tailed bat.

Even with advancements in radio telemetry, there are still engineering limitations as trackers get smaller and smaller. Chief among these is battery life. The smaller the device, the smaller the battery that can fit inside the device.

Researchers attach the trackers with temporary methods like glue or sutures that degrade over time. Usually, the transmitter will fall off after about six months, giving the trackers enough time to transmit crucial data over the course of a single migration season.

Motus tracking is helping researchers learn about the migration patterns of birds such as the lesser yellowlegs, which breeds in the forests of Alaska and Canada and spends the winter on the U.S. Gulf Coast or in South America.

Melody Lytle

Motus tracking is helping researchers learn about the migration patterns of birds such as the lesser yellowlegs, which breeds in the forests of Alaska and Canada and spends the winter on the U.S. Gulf Coast or in South America.

Melody Lytle

Why It Matters

On the Motus website, researchers can select an individual tagged animal and see where it’s been based off data collected by the receivers in the Motus network.

The importance of Motus is exemplified by the story of one lesser yellowlegs, a medium-sized shorebird that migrates from its breeding grounds of the boreal forests of Alaska and Canada to spend the winter on the U.S. Gulf Coast or South America. This bird passed by the Alazan Bayou station in East Texas and pinged 19 different stations on its way south, forming a line that zigs and zags east and west rather than straight down.

“Sometimes we have these ideas about their movement like, ‘Oh, they move in this straight line,’ and when you look at what they're actually doing, it’s a lot more complicated than that,” says Homayoun. “It opens up as many new questions as it’s giving us answers, and we’re questioning what we always assumed.”

With this kind of data about individual bird behavior, biologists are getting answers about where the animals are spending time and for how long. However, the why of it all remains to be investigated. Perhaps a bird or bat is staying in one spot because there’s more food available there, or maybe that location has better breeding habitat, or it could be one of a million other reasons. If a bird goes zigs and zags on its way south, maybe it’s tracing natural, historic migration paths, or it could be that human environmental changes have interrupted what was once a more linear route.

With Motus, conservation planners can get a better idea of which parcels are being used heavily during migration and focus limited resources there.

“These kinds of questions and answers affect the research we need to do next and help us understand what habitat interventions will have the most positive impact on the species,” Homayoun says. “Maybe we focus on preserving habitat in a certain place for one species, and perhaps another could greatly benefit from asking people to change behaviors that affect the species.”

But perhaps even more than concrete data, Homayoun is excited about the potential of Motus to provide impactful stories about individual birds to the general public. “Humans respond to stories. We are so responsive to a narrative, and this kind of research gives us a protagonist,” Homayoun says. “So I think that’s a really powerful conservation tool that comes out of this. A spreadsheet is great, but that's not what's going to win us hearts and minds.”