The South Texas thornscrub moves in whispers. A flick of a spotted tail, a shimmer of fur melting into mesquite shadows — and then nothing. For most Texans, the ocelot is more myth than mammal, so rare that fewer than a hundred remain in the United States. These elusive cats live deep in the brush country of South Texas, where the hum of traffic and the thunder of tropical storms serve as constant threats to survival.

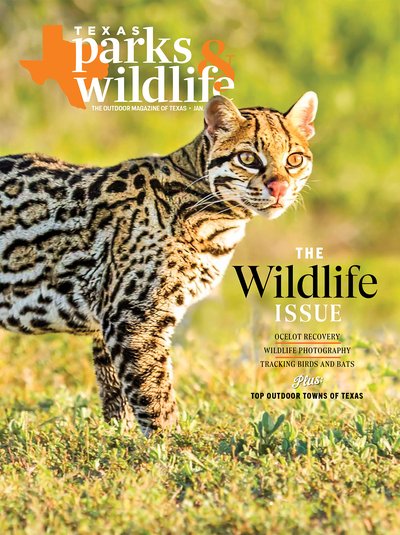

Ocelots' pattered fur helps them blend into the South Texas brush.

Ben Masters | Fin and Fur Films

Ocelots' pattered fur helps them blend into the South Texas brush.

Ben Masters | Fin and Fur Films

At the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Center of Texas A&M University-Kingsville, a new facility is underway to keep these wildcats from disappearing from Texas altogether. The $20 million facility will occupy nearly 30,000 square feet and is designed to serve as both a breeding program and a rewilding center. It aims to do something no project in Texas has managed: grow a population of ocelots resilient enough to withstand the highways, hurricanes and shrinking habitat that have pushed the animals to the edge of regional extinction.

“Because they’re concentrated on the coast, they’re vulnerable,” says David Hewitt, director of wildlife research for the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute. “A major hurricane, wildfire or a disease outbreak could wipe out a large portion of the population. In fact, a wildfire came dangerously close a couple of years ago, and it only stopped because the wind shifted. So, all of our eggs are basically in one basket.”

The immediate goal for recovery is to establish another ocelot population inland, farther from the coast, to reduce the risk that a single disaster could eliminate them and to provide much-needed genetic diversity.

Scientists collect measurements from wild ocelots.

Ben Masters | Fin and Fur Films

Scientists collect measurements from wild ocelots.

Ben Masters | Fin and Fur Films

Ocelots have excellent eyesight.

Ben Masters | Fin and Fur Films

Ocelots have excellent eyesight.

Ben Masters | Fin and Fur Films

Collecting data from ocelots is essential to conservation of the species.

Collecting data from ocelots is essential to conservation of the species.

A Struggle for Survival

For decades, ocelot populations in Texas have been stuck in a holding pattern: tiny, isolated groups clinging to coastal thornscrub, their numbers and genetic diversity dwindling.

Historical records show ocelots once roamed widely across South Texas, the southern Edwards Plateau and the coastal plain (ranging southward into South America), but as humans have reshaped the environment, less than 5 percent of the ocelot’s natural habitat remains in the state. Without cover, ocelots cannot hunt or hide; without protected corridors, they cannot find mates. Over time, their range contracted until only the current small populations were left. Roads were built through remaining habitat, and in the last 20 years, nearly half of all recorded ocelot deaths in Texas were caused by vehicle collisions.

Two Texas populations remain — one at Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge and one on private land.

“In Texas, ocelots are listed as endangered and now occupy only a fraction of their historical range,” says Daniel Kunz, technical biologist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “This project offers a way forward by boosting population numbers, improving genetic diversity and working with landowners to expand suitable habitat, all of which are essential steps toward the long-term recovery of this species in the United States.”

In recent decades, the Texas Department of Transportation has built 15 wildlife underpasses near Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge to reduce road deaths. Even so, the populations remain isolated, small and genetically vulnerable. Conservationists have found that small, fragmented populations are particularly susceptible to inbreeding, which can reduce fertility and increase disease. Without new genetic input, these populations face long-term decline.

In the face of worsening conditions for survival, an ambitious, restorative model for ocelot recovery is necessary.

This new effort aims to establish a new ocelot population in Texas and to increase the total number to at least 200 Texas animals for a period of 10 years — one benchmark needed to take it off the endangered species list.

Why Ocelots Matter

As to why the restoration of Texas ocelots truly matters, project partners emphasize both ecological and cultural reasons.

“Ecologically, ocelots help balance ecosystems. These populations are all interwoven, and if you start pulling pieces of that out, the community just becomes less stable, less resilient,” Hewitt says.

These small cats (they weigh between 15 and 35 pounds) are a keystone species. As apex predators that feed on rodents, rabbits, birds and reptiles, they help regulate prey populations, maintaining balance in the thornscrub ecosystem. They share prey with bobcats and coyotes but use different habitats, especially dense brush, which reduces competition. Hewitt says that the disappearance of ocelots would destabilize that balance in ways we don’t fully understand.

Ocelots matter not just to the ecosystem but also to local culture and land management practices. In South Texas, communities celebrate ocelots with festivals, and spotting one in the wild is a once-in-a-lifetime experience, making these rare cats a beloved part of the region’s natural heritage.

“Ocelots are super charismatic, and they’ve become an iconic species in South Texas,” Hewitt says. “Down in the Rio Grande Valley, a lot of towns have festivals dedicated to them. So there’s cultural value in maintaining ocelots.”

At the Ocelot Conservation Festival hosted each year by the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, visitors gather around the zoo’s two resident ocelots, one of the few opportunities in Texas where the public can see the cats

up close.

Finally, helping to recover ocelots in Texas would benefit landowners too. Not only will landowners have the privilege of hosting a rare species on their property, their conservation-minded actions may also contribute to decisions about the legal status of the species.

Young ocelots reach adult size when they are 8-10 months old.

Art Wolfe

Young ocelots reach adult size when they are 8-10 months old.

Art Wolfe

Ocelots are adept at climbing trees.

Rolf Nussbaumer

Ocelots are adept at climbing trees.

Rolf Nussbaumer

Project “Recover Texas Ocelots”

The ocelot Conservation Facility in Kingsville will be stocked initially with females from zoos and wildlife institutions across the country. Using assisted reproductive technologies, these cats will be bred with DNA collected from wild Texas males to produce cats with favorable traits for their intended habitat.

Researchers are hoping that mixing the Texan genetic stock with zoo females will bolster genetic health in the population.

Zoos across the U.S. have been breeding ocelots for decades with the goal of maintaining a protected population of the endangered cats. They have employed a variety of techniques to maximize the genetic diversity of the captive populations, and as a result, zoo ocelots today are a genetic mix that reflects the diversity found throughout their ancestral range in Latin America. Zoos have paired animals to reproduce naturally and applied assisted reproduction technologies, such as artificial insemination, to produce new cats. Impregnating captive ocelots with wild sperm, however, has never occurred.

“Animals adapt to their native environments,” Hewitt says. “Ocelots in Brazil, for example, live in rainforests with different food sources and seasonal cycles. They don’t experience droughts or the extreme temperature swings that Texas ocelots do. Texas ocelots may have developed local adaptations that help them survive here. We don’t know exactly what those adaptations are, but the fact that they persist in South Texas suggests they exist. By including Texas genetics in the breeding program, we’re hedging our bets to ensure released ocelots can handle the harsh local environment.”

The Kingsville facility will include a main research building with surgery and exam rooms, offices and space for public outreach, alongside 16 enclosures and four quarter-acre rewilding pens designed to prepare young ocelots for life in the wild.

There, kittens will undergo behavioral preparation, learning hunting and survival skills before release. According to program guidelines, released ocelots must have at least 75 percent ancestry from Leopardus pardalis pardalis, the subspecies native to Texas, Mexico and Central America.

The Kingsville facility is expected to be completed in 2026, but it will likely take years to produce ocelots ready to be released into the wild.

The first cats bred in Kingsville will be released onto the East Foundation’s San Antonio Viejo Ranch, a large ranch in Jim Hogg and Starr counties that's an oasis of the kind of landscape ocelots once thrived in across South Texas. “As land stewards, we support wildlife conservation and want to recover the ocelot,” says James Powell, communications director for the East Foundation. “Since we also are operating a cattle ranching enterprise, we also need to be sure that our ranches can continue working in coordination with ocelot reintroduction and conservation activities.”

With 95 percent of Texas privately owned, ocelots cannot recover without landowner support. In the past, ranchers worried that hosting an endangered species might lead to restrictions. To encourage private support of the species’ recovery, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officially approved a Programmatic Safe Harbor Agreement in March 2024 for ocelot reintroduction on private lands. Participating ranchers can continue with normal ranch operations while allowing ocelot dispersal, occasional monitoring and veterinary access if needed.

“Texans should know that ocelots still survive here largely because of the dedication of private landowners with a deep love for their lands,” Kunz says. Other major partners in the project include the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute and the Cincinnati Zoo.

The new facility will include a main research building with surgery and exam rooms, offices and space for public outreach, 16 enclosures and four quarter-acre rewilding pens.

The new facility will include a main research building with surgery and exam rooms, offices and space for public outreach, 16 enclosures and four quarter-acre rewilding pens.

Threats and Challenges

Despite recent momentum in conservation efforts, ocelots face steep odds. Even with greater numbers, ocelots will face risks from vehicle collisions, predation, competition and environmental conditions at any location in the wild. Researchers can and will do their best to set released cats up for success, but the reality is that the ocelots’ historic habitat no longer exists.

To improve their chances, every released ocelot will be fitted with a tracking collar. Biologists will follow their movements, monitor survival and provide veterinary care when possible. Each data point helps refine the reintroduction plan, giving the species a better chance.

The Future of the Ocelot

The Kingsville facility marks a turning point for Texas’ secretive wildcat. Conservationists are no longer just protecting fragments of habitat — they are attempting to restore what was lost. Success would mean inland ocelots reclaiming parts of their historical range, thriving beyond the shadow of extinction. Failure could be final: Texas could lose one of its most iconic native species. With so few ocelots left, the margin for error is thin.

Those interested in following the reintroduction process or supporting conservation efforts can visit RecoverTexasOcelots.org, where updates and donation links will be posted.

For now, the thornscrub holds its breath. Biologists set camera traps. Ranchers check for paw prints. And in Kingsville, the foundations rise for enclosures that may one day hold the first members of a program designed to give Texas’ most elusive wildcats a fighting chance.