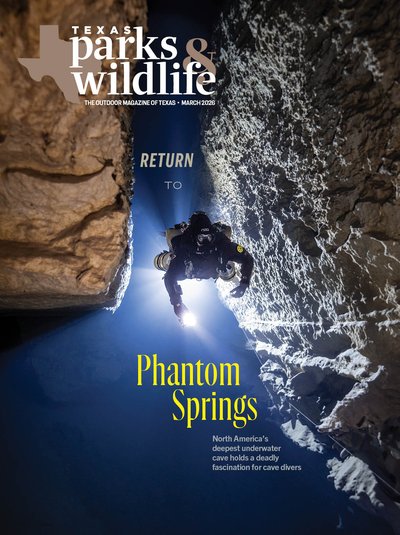

Andrew Pitkin faces the dark, damp walls inside Phantom Springs Cave. He’s half submerged, and silent, in a crystalline pool. Underwater lights make the water’s surface glow aquamarine, like a magic portal. On the other side lies the deepest underwater cave in North America.

Andrew Pitkin prepares to dive at Phantom Springs.

Andrew Pitkin prepares to dive at Phantom Springs.

The spring that fills the cave, part of the same large system that feeds the pool at Balmorhea State Park, is an anomaly in West Texas, where the surrounding Chihuahuan Desert stretches for hundreds of miles in each direction.

The Chihuahuan Desert is an unlikely place for a watery cave.

The Chihuahuan Desert is an unlikely place for a watery cave.

Pitkin has been here before. As one of the world’s premier cave divers, he’s one of a handful of people qualified to venture into the deepest reaches, where explorers have yet to find a bottom. On this visit, in December 2024, he’s not setting out to break records or make new discoveries. It’s his first trip back to Phantom Springs Cave since a deadly tragedy unfolded here a year earlier.

After cave diving for over 30 years, Pitkin has grown used to pushing physical and technical limits in unforgiving environments, but never before had he tested his emotional limits to this degree.

A pediatric anesthesiologist by trade, he knows how to shut off that part of himself when the time comes. “In my job, I see a lot of death all the time …” Pitkin said in the weeks leading up to his return. “But I don’t know how this is going to affect me when I’m actually there.”

Pitkin hardly questioned whether he would return to Phantom Springs. It was merely a matter of when. For people like him, the call of exploration can’t go unanswered. Propelled by the desire “to know what’s around the next corner,” Pitkin says he plans to continue exploring the cave as far as he possibly can. The risks, of which there are many in the hazardous pursuit of cave diving, are calculated like any other measurement tracked on the gauges and computers he dives with.

As his return to Phantom Springs drew near, his less rational instincts had whispered that there must be something evil about the cave, after all that it had taken.

Now, the day has come. Pitkin finds himself surprisingly calm. “It’s really hard to be mad at it in any emotional way when it’s just so beautiful. It’s got no animus or anything. It’s just a water-filled hole in the ground.”

Pitkin takes a breath, and plunges into the deep.

The gated entrance to Phantom Springs Cave.

The gated entrance to Phantom Springs Cave.

The year before, the orange glow of sunrise was fading away as Pitkin and his dive partner, Brett Hemphill, hauled loads of diving equipment through a corroded iron gate into Phantom Springs Cave. The narrow entrance to the cave yawned open as a beehive in the limestone cliff above buzzed steadily louder.

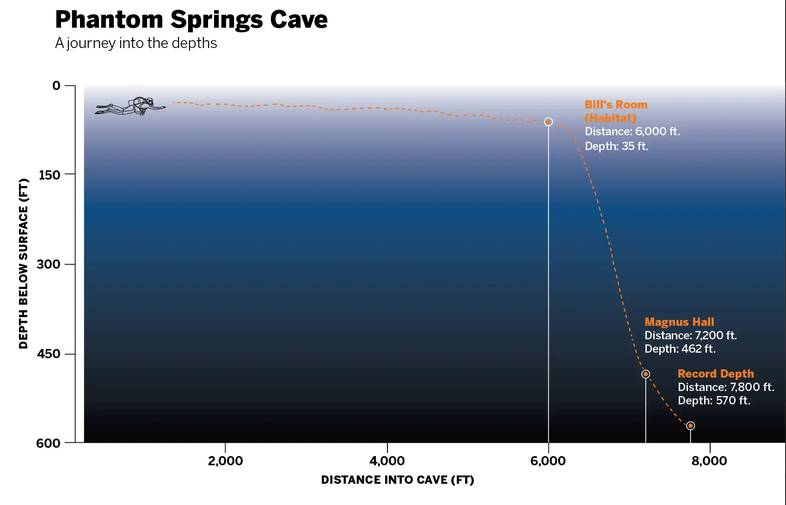

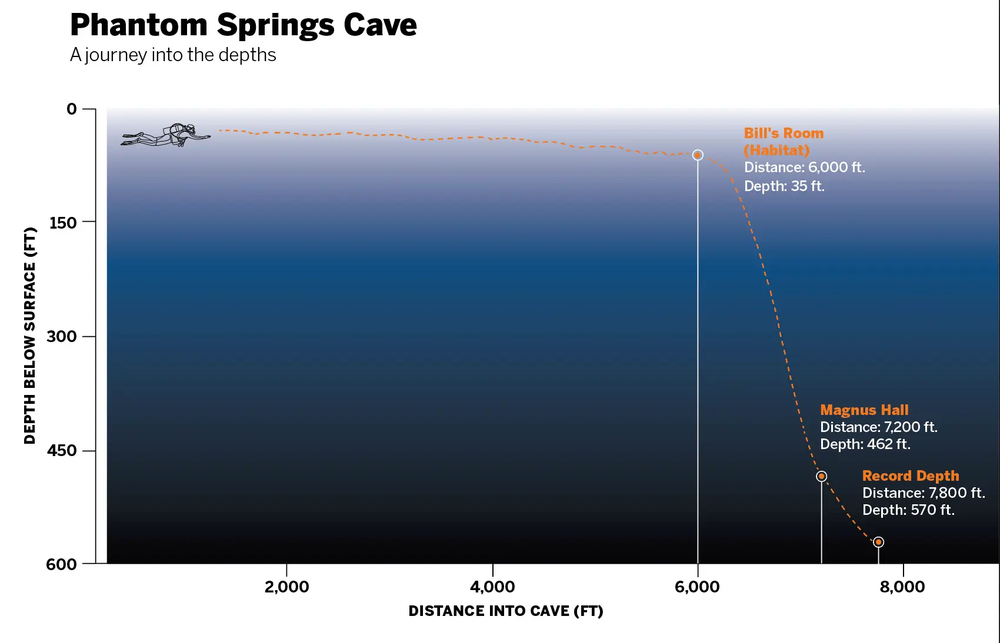

This pair of world-class divers from Florida set a North American cave diving depth record here in 2013, when they ventured 462 feet below the water’s surface. Ten years later, on this cool October morning in 2023, they tested gauges, lights and hoses with a soldierly discipline that masked their excitement as they prepared to push their physical and technical limits in an attempt to reach a new record of 600 feet.

Once inside, the two men equipped themselves in full dry suits and advanced scuba gear before stepping into the water, which remains between 75 and 77 degrees Fahrenheit all year. At 10:45 a.m., they sank beneath the surface. Members of their support crew watched as their lights faded into the darkness.

They had a long, perilous and ambitious journey ahead. On that morning, Hemphill and Pitkin were in for a dive that would easily surpass eight hours, if everything went according to plan. With the use of closed-circuit rebreathers, they could stay underwater for hours without carrying dozens of gas cylinders into the cave.

Cave diving, a combination of scuba diving and spelunking, is extraordinarily dangerous for several reasons. It's often compared to spacewalking because of the hostility of both environments and its rigorous demands on the body. In cave diving, there’s no direct access to the surface. Equipment can fail. Silt-outs can reduce visibility to zero in seconds. Disorientation in the labyrinthine tunnels can be fatal. In the pitch-black darkness, headlamps or flashlights provide the only source of light.

Once inside the cave, Hemphill and Pitkin navigated a short, maze-like section of interconnected passageways. Just a few minutes into their dive, they reached the cave’s main artery, a wide, river-like channel. To the left, a strong current beckoned like a siren’s song toward the less-explored “downstream” section of the cave. On that day, they turned right, into the current, to continue their exploration upstream.

For about a mile, they swam, with the help of motorized diver propulsion vehicles, through large underwater passageways with crystal-clear water and jagged limestone walls the color of curdled milk. The journey formed a saw-tooth pattern as the main channel repeatedly dipped and then rose again, never dropping below a relatively modest depth of 60 feet. “It’s a spectacularly beautiful cave,” Pitkin says, one of the most striking places he’s dived in 30 years of exploring underwater spaces around the world.

Preparing equipment for a dive.

Preparing equipment for a dive.

In the previous days, they’d implemented several safety measures to assist their potential record-breaking push. Six thousand feet into the cave, they reached the decompression chamber, a jellyfish-shaped, air-filled balloon, that they’d installed earlier that week. This “habitat,” as divers call it, was located at a critical juncture within the cave, at a threshold before it quickly plummets to uncharted depths. Inside the habitat, they could rest, eat, talk and communicate with a support crew at the surface via wired communications lines. Later, they planned to spend several hours inside waiting out a lengthy decompression stop.

Past the habitat, at the far end of the chamber, they saw a ledge where the passage steeply plunges.

That’s where they were headed.

The "habitat" is a decompression chamber where divers can rest and communicate with support crew.

The "habitat" is a decompression chamber where divers can rest and communicate with support crew.

Hemphill and Pitkin's fascination with Phantom Springs came about in the early 2010s. Hemphill was president of the Florida cave exploration organization Karst Underwater Research (KUR) when Tom Iliffe, a National Geographic Explorer and professor of marine biology at Texas A&M University at Galveston, contacted him about an intriguing West Texas cave he’d read about in Texas Caver magazine. Phantom Springs looked like a biological treasure trove, and Iliffe, who studies cave-adapted organisms, wanted to put a team together to explore.

“I wanted people who were the best explorers,” Iliffe recalls. So he called Hemphill, whom he’d met on a research trip years before. “Is this something that you guys might be interested in?” Iliffe asked. “He says, ‘Hell yeah,’ you know? And he says, ‘Let me bring out a crew.’”

As usual, Hemphill wanted Pitkin as his diving partner for the trip.

Brett Hemphill and Andrew Pitkin

Courtesy Brett Hemphill Family

Brett Hemphill and Andrew Pitkin

Courtesy Brett Hemphill Family

Pitkin and Hemphill had met shortly after Pitkin moved to Florida in 2007 through the state’s insular cave diving community. Pitkin describes his dive partner as an extrovert who knew hundreds of people. “I'm kind of the opposite. I'm much more introverted.” Their different personalities complemented each other during long, technical dives.

Pitkin’s bookish, soft-spoken demeanor belies an intense meticulousness. A pediatric anesthesiologist by day, he spends his off time not only exploring caves, but overseeing related electronics work and research.

Hemphill, who had an encyclopedic knowledge of Florida’s caves, was as well known for his charm as his cave diving prowess. He filled his hours outside caves singing and playing music. Sometimes, his flamboyance gave way to recklessness. “‘Brett’ and ‘very careful’ don’t really belong in the same sentence,” says fellow KUR member Jason Richards.

Before an expedition in Florida, Hemphill jumped into a pond with nothing but the clothes on his back to wrangle a 3-foot alligator from inside the cave entrance. In another instance, he free-dove into a Mexican cenote with only a flashlight to investigate the new cave. Hemphill undoubtedly possessed some of the swagger typical of adventurers of his caliber, but colleagues say it never came at the cost of extreme care and attention while on a serious dive.

Fred Stratton, chairman of the National Speleological Society’s Cave Diving Section, says Pitkin and Hemphill’s extensive explorations of underwater passages have placed them in a league with few others.

“Of the people who are qualified to do that, and have explored to those depths, I say you’re looking at just a few dozen people capable of doing that in the world,” he says.

Once they moved past the habitat, Hemphill and Pitkin continued their descent.

Hemphill led the way, laying thin nylon line to mark their passage. Pitkin followed 15 feet behind, adjusting the line as they went. During their descent, they entered Magnus Hall, the 60-foot-tall, 100-foot-long chamber where they’d set the cave’s previous depth record. They continued, passing 472 feet of depth, the standing North American cave diving record set by a team of divers in Missouri two years earlier. They’d celebrate later. With an unspoken acknowledgement of the accomplishment, they kept a laser focus on their dive.

In 15 years of diving together, their underwater communication had become instinctual.

“I didn’t need to signal him or anything for him to know how I was feeling or what I was thinking underwater,” Pitkin says. “I could look at him and I could tell what his state of mind was just by how he was moving and how he was acting. I could tell whether he was comfortable or whether he was anxious.”

When Hemphill tied off the line at 570 feet of depth, setting a new record, Pitkin knew it was time to turn the dive around and head back toward the habitat. Beyond the end of the line, the two could see that the cave continued its slow descent into the abyss. Pitkin heard Hemphill shout a muffled cry through his mouthpiece: “Andy, we did it!”

At that distance below the surface, their bodies were under tremendous pressure — more than 16 times the atmospheric pressure experienced at sea level. In this extreme environment, there wasn’t a moment to waste. They started their ascent. As they progressed, Pitkin began taking survey notes — distance, bearings, incline.

Pitkin’s hands were shaking as he took notes on his diving slate. His heart rate was 150 beats per minute. “It’s a stressful environment, and there’s a lot of emotional stress down there,” Pitkin says. The shaking may have been stress, or it may have been the result of high-pressure neurological syndrome (HPNS), a condition that can cause tremors, dizziness, drowsiness, cognitive impairment and, in some severe cases, seizures — one of the many potential hazards of diving at such extreme depths.

Eventually the two made their way back into Magnus Hall.

As Pitkin began surveying uncharted areas of the room, he saw Hemphill’s light shining in his peripheral vision, “pretty stationary over to my left, you know, just hanging out there like he would typically do.”

Pitkin moved to the top of the chamber to survey one final section of Magnus Hall. When he finished and looked for Hemphill, his diving partner was gone. That wasn’t unusual — Hemphill often ventured off on his own while Pitkin was absorbed in measurements.

He covered his light. In the pitch-black darkness, Hemphill’s light should’ve shined like a beacon.

Nothing.

Bill Tucker and his crew were early explorers of Phantom Springs.

Courtesy Bill Tucker

Bill Tucker and his crew were early explorers of Phantom Springs.

Courtesy Bill Tucker

Phantom Springs has been attracting and challenging divers for decades. In the 1950s, a team of three amateur scuba divers traveled to Balmorhea to test their new Aqua-Lungs, the first commercial market scuba gear. While there, “we heard about this underground river which comes out of the side of a small hill,” James Thompson, one of the divers, told the El Paso Herald Post in a 1957 article about the expedition. The trio was able to venture at least 900 feet into the cave.

The cave could be a perilous place. That same year, two swimmers perished in the cave. Later, in 1983, two inexperienced young divers snuck into the cave and lost their way in the maze of passages near the entrance. They were unable to find their way out before exhausting their air supplies.

When Bill Tucker, now a longtime diver and gear expert, first visited the cave in 1976, he was essentially an amateur. He and five similarly underexperienced friends set about exploring the cave with double air tanks and reels to hold heavy nylon line.

“We really didn’t know what we were looking for,” Tucker recalls.

Over a long weekend in West Texas, Tucker and his friends acquired a respect for the cave bordering on fear. As they explored the labyrinth of passages near the entrance, they realized it would be easy to lose their way. At one point, Tucker looked down at the reel he’d wound with 1,000 feet of line. It was empty.

“I don’t recall ever feeling that small before,” Tucker wrote in an expedition report. “I don’t think that I have ever seen anything as beautiful as the daylight shining through the azure-blue water at the cave exit.”

But if Tucker was frightened of the cave, he was equally in awe of its massive passages and clear water. Nearly 20 years later, he finally planned his return. Tucker connected with Dean Hendrickson, a biologist and curator at the University of Texas' Memorial Museum in Austin, and together, they acquired a permit to conduct a biological survey of Phantom Springs Cave.

In the time since his first visit to Phantom Springs, Tucker obtained experience and formal cave diving certifications that prepared him for deeper exploration. For this new expedition, in 1995, he’d be joined by a similarly credentialed team to help collect biological specimens, create maps and surveys, measure water flow, install pumps and continue exploration of the cave.

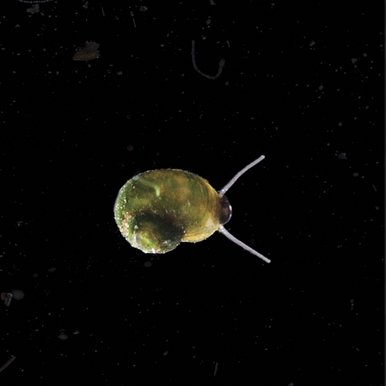

When Hendrickson arrived at the cave, he observed a thriving and diverse ecosystem living in the ciénega at Phantom Springs and further into the cave itself. Softshell turtles swam deep into the cave, beyond reach of the sun’s rays. Catfish prowled the silty floor. Small organisms like snails and aquatic invertebrates made their home in roots dangling from the chamber roof.

The collaboration between Tucker and Hendrickson resulted in the discovery of at least five previously unknown, cave-adapted species at Phantom Springs: two isopods, a snail, a silverfish and a spider. Several of the species, including the tiny, translucent Phantom Springs snail, only half a millimeter in diameter, are endemic to the cave, meaning they are found nowhere else.

Cave Dwellers

Researchers have discovered at least five previously unknown cave-adapted species in Phantom Springs.

Phantom Springsnail - Pyrgulopsis texana

Phantom Springsnail - Pyrgulopsis texana

Isopod - Lirceolus cocytus

Isopod - Lirceolus cocytus

Silverfish - Texoreddellia capitesquameo

Silverfish - Texoreddellia capitesquameo

Spider - Eidmannella tuckeri

Spider - Eidmannella tuckeri

“Every day we were pushing further and seeing things nobody had ever seen, and that was a great feeling,” Tucker recalled.

In the coming years, Tucker would accumulate more than 100 dives at the cave and become its most prolific explorer. Each trip took the Tucker team deeper into the cave.

In the less-explored, downstream section, the underground river pulled them into a long, deep darkness that could go all the way to Balmorhea. “It’s kind of a spooky feeling, like you’re being pulled into the bowels of the earth,” Tucker says. To return to the surface, Tucker and his fellow explorers had to pull their way out, gripping onto the limestone hand-over-hand like rock climbers to fight the flow. In the other direction, Tucker made it more than a mile upstream, to the room that would later house the habitat, before reaching his limit.

By the time Hemphill first set foot in the cave in December 2012, dive technology had advanced considerably, making that trip into the bowels of the earth more possible for divers. Closed-circuit rebreathers, which allow divers to reuse the air already in their lungs by filtering out or “scrubbing” carbon dioxide with substrates like soda lime, became commercially available in the mid-’90s but weren’t adopted for mainstream use by recreational divers until the early 2010s. This technology greatly extends the time divers can spend underwater and enabled the KUR team to reach new depths within Phantom Springs.

During that first trip, they pushed exploration of the cave to 237 feet of depth. They returned the following year, in 2013, prepared to undertake a much more serious level of diving. In that trip, they reached 462 feet beneath the surface, securing Phantom Springs’ title as the deepest underwater cave in North America.

This success turned out to be a double-edged sword. For too long, the explorers had teetered at the edge of the Bureau of Reclamation’s capacity for risk. After KUR set the new record at Phantom Springs, the potential for disaster, and liability, became too high for the comfort of the agency, which controlled access to the cave for several years. The Bureau of Reclamation withdrew the divers’ permit to explore.

Ultimately, the Bureau of Reclamation determined that control of the cave was no longer part of the agency’s mission and transferred ownership back to the previous landowner.

Hemphill never lost his desire to return to Phantom Springs. His determination to further explore the cave led him to a birthday party in Tilden, Texas, in spring of 2023. Buck Hamilton, who owns Phantom Springs, was hesitant to grant permission, so Hemphill flew out to Texas to plead his case.

Hemphill’s warm personality earned him an invitation to stay for a barbecue lunch, the birthday celebration for one of Hamilton’s grandchildren. As they sat on the back porch overlooking the cows and mesquite trees, Hemphill regaled the family with stories about Phantom Springs and his adventures in caves around the world. A few days later, when Hemphill boarded his flight home to Florida, he carried a signed agreement permitting KUR’s return to Phantom Springs.

In the decade since Hemphill and Pitkin's last trip to the cave, the depth record had been surpassed by a team exploring Roaring River Cave in Missouri. That project, which established a depth record of 472 feet, came to an abrupt halt in October 2022 after the death of explorer Eric Hahn.

Scuba divers follow a nylon guide cord in Phantom Springs Cave.

Scuba divers follow a nylon guide cord in Phantom Springs Cave.

Upon noticing Hemphill's light was missing, Pitkin didn’t immediately panic.

Odd, he thought, but perhaps his friend had already turned back toward the habitat. He headed that direction to look for him. As he swam through the passages away from Magnus Hall, he noticed something that troubled him: the water was pristine. Too pristine.

As divers ascend, decreasing pressure forces them to release expanding gases. When the bubbles hit the ceiling, they dislodge silt that rains down from above. “Sometimes, and in Phantom in particular, (the silt) can be very severe,” Pitkin says. The silt can dramatically reduce visibility. “That’s the point when I started getting definitely worried.”

Pitkin backtracked into the deeper chambers. As he rounded a corner before re-entering Magnus Hall, a massive wave of silt washed over him, reducing visibility from 60 feet to six inches.

Pitkin quickly grabbed hold of the line. In a silt-out, the nylon cord that divers use to chart their course becomes a lifeline. If they lose sight of it, they’ll likely never find it again. “I just stopped there and thought, ‘Well, what the hell am I going to do now?’” Pitkin says.

He knew Hemphill must have been the source of the silt-out in Magnus Hall. He could imagine Hemphill entangled in the line, disoriented from the silt or trapped in a narrow channel between two cave walls. There was no shortage of possible scenarios.

“What I was pretty sure of was that descending into a very large room with that kind of visibility was just pointless,” says Pitkin, who was already pushing the limits of his dive.

With near-zero visibility, venturing back into Magnus Hall would have been a risk both to Hemphill and himself. If escape was possible, Pitkin had to trust his friend would find it. After diving with Hemphill for so many years, Pitkin had seen Hemphill dig himself out of any number of life-threatening situations. “He always fixes it. You know, he’s so capable. He was so capable.”

If his friend had perished, there would be no way to safely recover his body without help and necessary equipment.

Out of options, he turned back toward the habitat.

It was a slow trip. To avoid decompression sickness, a serious condition caused by the accumulation of nitrogen in the body at extreme pressures, divers must make long stops at multiple points as they return to the surface. Decompression sickness can cause dizziness, weakness, confusion, fatigue, numbness, tingling and, in severe cases, paralysis and death. Pitkin was deeply familiar with the symptoms. In the 1990s, he ran a hyperbaric facility at England’s Institute of Naval Medicine, where he treated and researched the illness.

As he approached a decompression stop at 160 feet, his back started to hurt. Not the familiar ache of carrying 40 pounds of equipment for hours. Something different. His skin started to tingle.

Then, a pins-and-needles feeling extended all the way down to his feet, indicating a potentially life-threatening problem. If he lost use of his legs, Pitkin would never escape Phantom Springs.

“At that point the only thing I could do was go deeper.”

Deep in the cave, and alone, Pitkin assessed his situation. The pins-and-needles feeling he was experiencing receded after he retreated to 300 feet underwater. The injury surprised him. He’d used the correct mixture of gases. He’d taken his time descending into the cave. But, at this depth, the field is ripe for the unexpected.

Deep-sea “saturation” divers allow their bodies to acclimatize to conditions they’ll face on the ocean floor by spending time in a pressurized chamber pumped with gases that mimic the effects. Once they’re fully “saturated,” they live at depths of up to 1,000 feet to work on construction and infrastructure projects. They’ll often spend 28 days under these conditions, and at the end they undergo a single, long decompression.

Technical divers like Pitkin and Hemphill do the same thing, but much, much faster. They drop hundreds of feet in a matter of minutes and then return to the surface over the course of a few hours and multiple decompression stops.

The additional time Pitkin spent at extreme depths while looking for Hemphill had nearly doubled his required decompression time. Almost six hours after he began his initial ascent to the surface, Pitkin still hadn’t reached the habitat. As he waited on the line 20 feet below the decompression chamber, he saw two KUR members, Bob Beckner and Gary Donahue, swimming toward him. They’d ventured into the cave with snacks, water and other supplies, expecting to find Hemphill and Pitkin in the habitat, tired and hungry.

As Beckner approached, Pitkin wrote an anguished message on his diving slate: “I lost Brett.”

Beckner and Donahue hadn’t brought the supplies necessary to dive deep enough to search for Hemphill. He wrote back to Pitkin that they would return to search for their friend.

Shortly after they left, Pitkin finally entered the habitat and made contact with the other KUR members via the wired communications lines. After alerting them to the situation, he sat in silence.

Normally, the habitat is a place of rest and celebration. Pitkin had downloaded movies to watch with Hemphill while they passed the hours in the habitat. Instead, Pitkin found himself alone, coming to terms with the fact that his friend likely wouldn’t resurface alive.

“I didn’t feel anything, any kind of sadness or sense of loss at that point,” Pitkin recalls. “I just felt completely numb.”

After five more hours of decompression, a difficult ascent still stood between him and the exit. After back-and-forth traffic of multiple divers, the chambers were badly silted. He followed the line blindly toward the exit, bumping into the walls and hardly able to tell up from down, until 800 feet from the entrance, where he hit clear water.

He emerged from the cave at 3 a.m. on October 5, 16 hours after the dive began.

Three days later, two KUR divers entered the cave to search for Hemphill and found his body at the bottom of Magnus Hall. Both of his rebreathers were still on and functional with gas remaining. An investigation of his death later determined that Hemphill likely suffered a heart attack, possibly induced by hostile conditions at depths where fewer than 100 recreational divers have ever been.

Hemphill and Pitkin shortly before departing on their last dive together at Phantom Springs.

Bob Becker

Hemphill and Pitkin shortly before departing on their last dive together at Phantom Springs.

Bob Becker

Phantom Lake, the cave's outer pool, is long gone, its waters having retreated into the cave. Only a small pool of water remains. Even so, some light-dependent organisms still cling to survival by the dim rays of sun that filter in through the narrow entrance. A bone-dry, rocky steam bed sits in the sunlight a few yards away, a reminder of the pristine ciénega that once was.

Inside the cave, there are scars, too.

During Pitkin’s visit in December 2024, his first time back to the cave since Hemphill’s death, Pitkin noticed that the tragedy had left a physical mark on the cave. “You can see where things have been dragged through the silt, undoubtedly related to the recovery,” Pitkin says.

The loss of Hemphill was a tragic blow for Pitkin. “He was my dive buddy,” Pitkin says. “I mean, we did so much together... we did all the big stuff together. It was a massive, massive impact.”

But back in the place where his friend had died, Pitkin wasn’t dissuaded from continuing his exploration in Phantom Springs Cave. Instead, his search for the bottom was renewed.

The cave could potentially descend much deeper — far past the limits of modern diving capabilities. Kevin Urbancyzk, a professor of geology at Sul Ross State University, says it’s possible, though unlikely, that the cave channel could remain swimmable for the entirety of its length. “If that flow path is that open at Phantom, there’s the possibility they could swim all the way to Van Horn,” where the water originates, more than 60 miles away.

If so, Pitkin and other divers would eventually reach a point where it would be too dangerous or too logistically difficult to go any deeper.

Currently, the KUR team is planning for a future dive at Phantom Springs in which they’ll attempt a depth of 700 feet. If they break their previous record, Pitkin says he’ll allow himself the celebration, and the mourning, he’s postponed since the loss of his friend.

Despite the risks, Pitkin wouldn’t call himself a thrill seeker. “(Hemphill and I) were both pretty risk-averse,” he says. The two went to great lengths to implement and improve safety procedures in their dives. But even with the utmost care and preparation, in some circumstances, like cardiac arrest, there’s simply nothing to be done.

Fred Stratton of the National Speleological Society says the world needs explorers like Pitkin and Hemphill to inspire and push boundaries.

“Some people say, ‘Oh, it’s selfish going to those depths’ … well, you could say that about anybody who did something that pushed the boundary,” Stratton says. “The Wright Brothers, Lindbergh trying to fly across the Atlantic, any number of people who took a calculated risk and advanced mankind.”

Pitkin isn’t in it for the glory. He does, however, revel in the experience of seeing places no one has been before. “All the mountains have been climbed,” Pitkin says. “We know exactly what’s on every inch of the moon, practically, but you don’t know what’s underground until you actually go there.”