Rattlesnake bites, pistols drawn, screaming women and blood-covered trips to the courthouse — all just another day for a Texas game warden in the 1960s. My father, Raymond Urban, worked six decades as a Texas lawman, and it all started out west in the rugged Guadalupe Mountains.

West Texas was a long way from West, Texas, the Czech-American community where Urban grew up. After serving in the U.S. Marine Corps, he was hired as a game warden trainee with $305 monthly pay. “I was very excited,” says Urban, who began training immediately alongside wildlife biologists, counting and reporting deer feces. “This did very little for me,” he recalls.

The fresh-faced rookie soon saw some action, arresting his first deer poacher while training with a game warden in Albany, about half an hour northeast of Abilene. Far more memorable was the night he first faced the barrel of a gun. “I’ll never forget it,” he says. On his first shift working the lead position, he was driving the game warden’s pickup when they spotted a suspicious campsite. They rolled up, headlights off, then sprang the trap. “I sped up and slid into this camp area, jerked my headlamps on and bailed out of the pickup,” says Urban. “Dead silence.” He saw no one. Then his partner’s voice boomed out: “Drop the gun! Dammit, drop the gun!”

A man in the shadows was pointing a pistol right at Urban. Urban drew his revolver, yelling, “Game warden! Drop the gun!” The man complied, his hands shaking. “He was scared to death.” A Dallas city slicker on his first hunting trip, he was guarding his buddies’ campsite and assumed the wardens were gun-toting bad guys. “Kennedy had been shot in Dallas a few days earlier, and he said he had that on his mind,” says Urban. “He probably remembers that day as well as I do.”

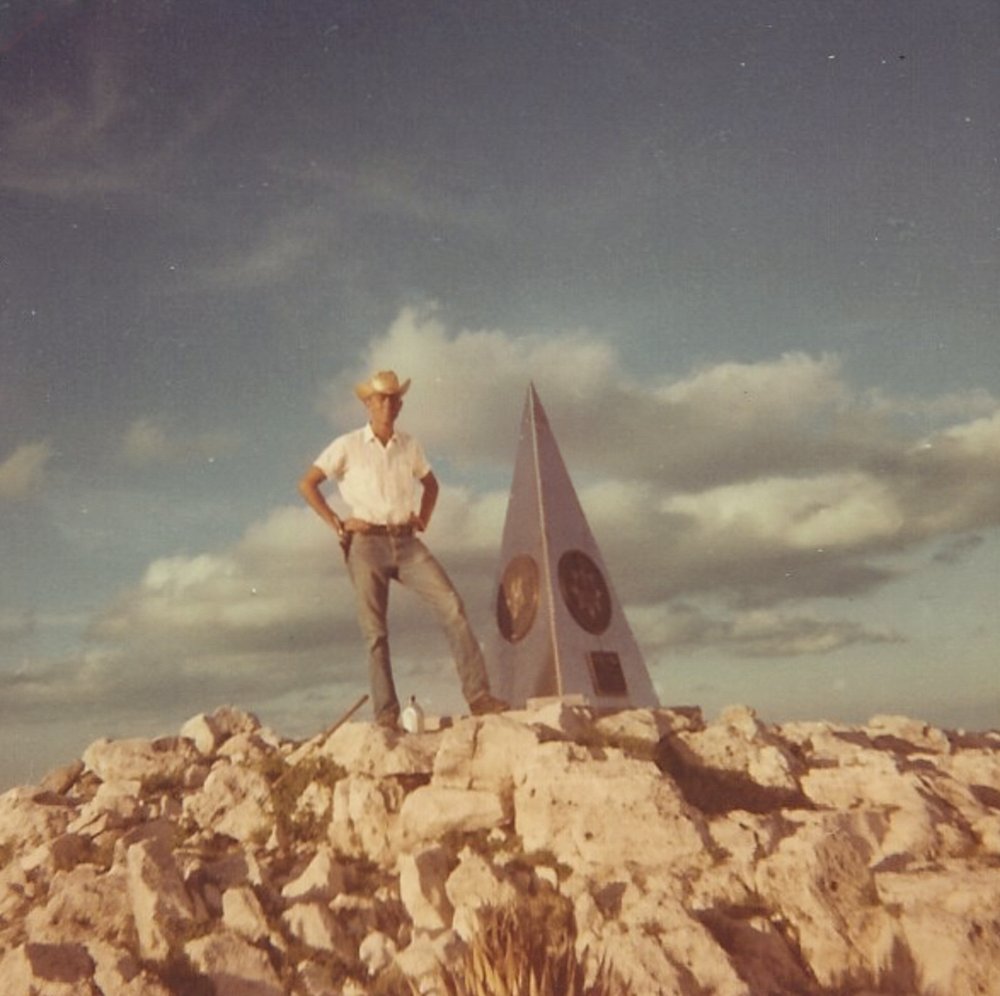

After graduating from game warden school at Texas A&M, Urban received his assignment: McKittrick Canyon in the Guadalupe Mountains. “It was a different kind of country than where I had been raised, with big, big ranches.” He lived at Ship on the Desert, a 1940s modernist-style rock house built by Wallace Pratt. Pratt had recently donated the home and 5,600 acres to the National Park Service, a major catalyst for Guadalupe Mountains National Park’s establishment in 1972.

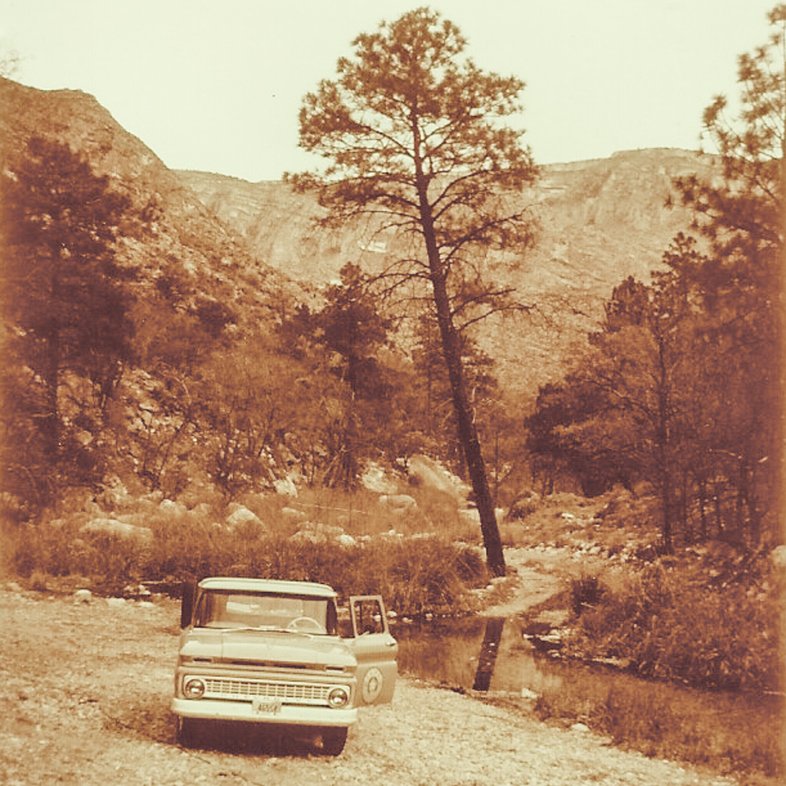

Game warden pickup in McKittrick Canyon.

Urban Family

Game warden pickup in McKittrick Canyon.

Urban Family

“As far as I know, I was the only game warden ever stationed up there in the mountains,” says Urban, who loved his remote outpost. “It was windy a lot of the time, usually nice and cool. People were few but wonderful.” Mule deer, antelope and porcupines lived in the mountains, and he often camped up high to survey elk. Working six or seven days a week, he patrolled 100 miles in every direction, visiting ranches spanning thousands of acres. Ranchers appreciated his presence and welcomed him warmly, providing gate keys and plenty of steak.

One particularly cold night, he stayed out late following a tip about New Mexico poachers. When a pickup with New Mexico plates appeared, he quickly pulled them over. “I was psyched up.” Two nervous men fidgeted in the cab. “Lo and behold, they had a deer in the back … as legal as it could be.” But a tarp beside it, thrown over something, looked highly suspect. Urban couldn’t be sure.

“I didn’t want to show that I was a novice game warden — which I was — so I thought, I’ll just reach under the tarp and feel. If it’s camping equipment or something, I won’t say anything. If it’s a deer, then I’ll arrest their ends.” He quietly slipped his hand beneath the tarp and felt something soft and warm. A fresh kill? “I squeezed it — and this girl screamed bloody murder.” He jumped back as the shriek rang out through the frigid West Texas air. “Two women were back there snuggling up keeping warm; they couldn’t all fit in the cab.” Embarrassed, he told them to get out of there. “That ended my night with no arrests.”

But usually he did find illegal game, and went out of his way to take the confiscated animals to St. Margaret’s Orphanage in El Paso. “They needed the meat,” he says. “The nuns were very thankful to get the deer and antelope. They ate every last part.” When a U.S. customs agent called with a 20-gallon tub of confiscated fish, Urban knew just what to do. “The orphans had a big fish fry that night.”

Urban was transferred to El Paso in 1965, but his patrol area didn’t change — and the poachers kept coming, like two men in a Cadillac with one deer in the trunk and another under the backseat. “They had pulled the seat out and put the deer inside, then set the seat on top of it.” But the animals hadn’t been field dressed, which was no good for the nuns. So Urban and the men went to work. “They didn’t know how to gut a deer, and I didn’t know a whole lot more. But we got it done. We all three got blood all over us.” Escorting them into the courthouse later, “I noticed a lot of people giving me dirty looks … then I realized it must have looked like I beat the living crap out of them.”

Yet he also got to be a hero. A distraught couple flagged him down on the highway: The man had been bitten by a rattlesnake, and El Paso’s hospital was 90 miles away. “I loaded them in the patrol car and drove wide-open to the hospital. The woman was extremely upset and kept yelling at me to go faster.” ER medics first treated the woman, whom they had to sedate before helping her snakebitten husband. “I agreed, because I had been listening to her rant all the way to the hospital.”

In 1967, Urban joined the Texas Highway Patrol. He served in an elite guard unit at San Antonio HemisFair ’68 for Texas Gov. John Connally, who was also shot during Kennedy’s assassination and wanted additional security. Urban worked for the Texas Department of Public Safety until 1996, then became a special deputy U.S. marshal until retiring in 2022. Now 86, Urban recounts his game warden days with enduring fondness for the people he knew and the wild West Texas landscape. “It was very rewarding,” he says. “I enjoyed every minute.”