A potentially devastating threat to wildlife and livestock is slowly making its way toward Texas: a small, red-eyed fly called the New World screwworm.

“The larvae of this fly feed on living tissue from warm-blooded animals,” says Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Big Game Program Director Kory Gann.

The flies look for wounds, as well as mucous membranes, to lay their eggs, and the resulting infestation is known as myosis. Infestations can become severe, and can cause death when left untreated. “A New World screwworm infestation can have significant impacts on livestock and wildlife health,” says Gann.

The destruction caused by New World screwworms is nothing new; prior to the 1980s, these flies were common pests across the United States. Thanks to innovative scientists (many of them working in Texas), the flies were eradicated from the country using a method called the sterile insect technique. The flies are now threatening to make a comeback in the U.S., slowly moving north across Mexico. While it will be no easy feat, Texas Parks and Wildlife officials and partners are optimistic we can fight this pest again.

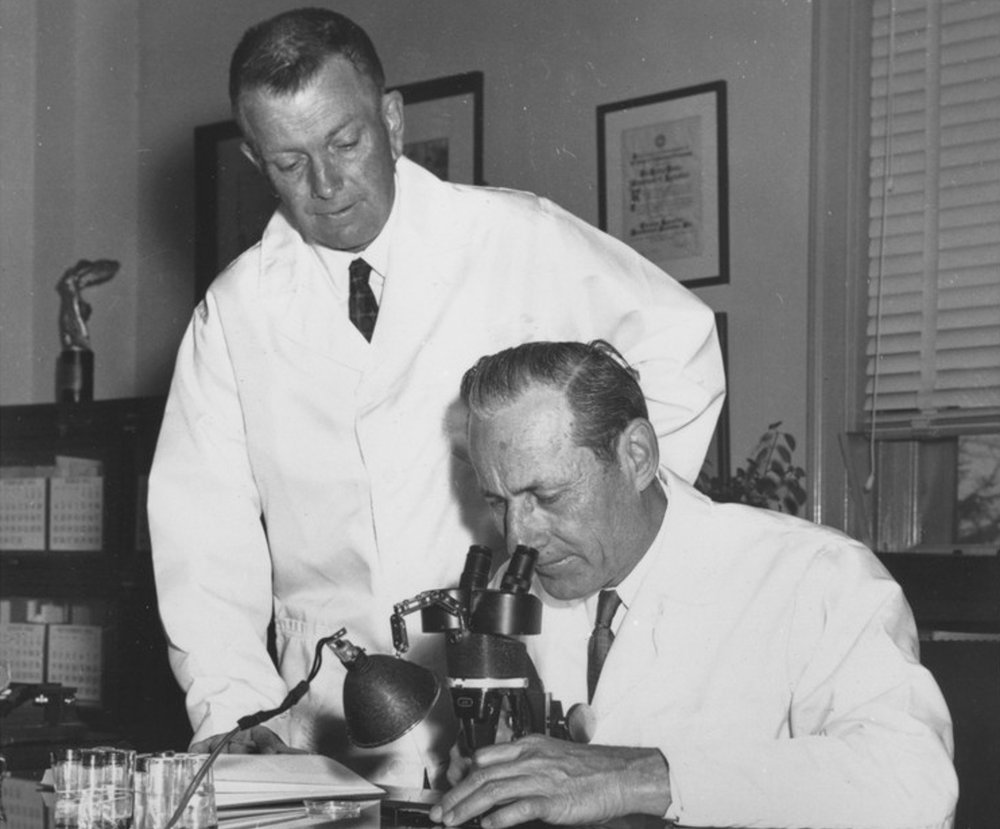

Edward F. Knipling (seated) and Raymond C. Bushland in the laboratory.

USDA National Agricultural Library

Edward F. Knipling (seated) and Raymond C. Bushland in the laboratory.

USDA National Agricultural Library

A Texas Innovation

To understand what lies ahead when it comes to the New World screwworm, it’s helpful to take a look into the past — specifically, at the sterile insect technique. The foundation for the technique was invented in 1928 at the University of Texas at Austin, by scientist Herman J. Muller. Muller used a dentist’s X-ray machine to expose male fruit flies to radiation, which rendered them sexually sterile.

At the time that Muller learned to sterilize fruit flies, New World screwworm was ravaging livestock across the country. Muller’s work inspired entomologists Raymond C. Bushland, a South Dakotan working for the USDA in Texas, and Edward F. Knipling, a native of Port Lavaca and screwworm expert.

For Knipling, the fight against screwworm was personal; as a child, he had the unfortunate job of picking screwworm maggots out of the wounds of livestock. In adulthood, he dedicated his career to stopping them.

As he was brainstorming methods to combat the pest, one fact stood out to Knipling: Male screwworm flies mate up to a dozen times, but females mate once, and then never again. As he mulled over this behavior, Knipling came up with what some scientists would later call “the single most original thought in the 20th century.”

Knipling’s idea was as follows: He and collaborators would irradiate 5- to 6-day-old screwworm pupae with gamma radiation. When the pupae grew up, the resulting adults would be sexually sterile. Then, the researchers could release large numbers of these sterile flies into the environment by dropping them out of planes. As the sterile males mated with wild female flies, the sterile flies would use up the females’ one shot at mating, preventing the females from producing any offspring. Because fly generations are quite short, the whole population could be eradicated quickly given enough sterile flies.

As with many scientific advancements, Bushland and Knipling’s efforts were met with ridicule. But results proved they had merit. Experiments on the Caribbean island of Curaçao and Sanibel Island off the coast of Florida showed that the introduction of sterile flies could effectively wipe out the screwworm population of an entire island.

The researchers, with the help of organizations across the country, scaled up their approach, opening sterile fly breeding facilities to produce millions of flies each week. By 1966, the screwworm fly was fully eradicated in the United States. Knipling and Bushland’s work has since informed eradication efforts for other insect species, and remains a proud achievement of Texas science. Today, researchers continue their work at the Knipling-Bushland U.S. Livestock Insects Research Laboratory in Kerrville. “It’s pretty neat that all this stuff initiated here in Texas,” says Gann.

Knipling (fourth from left) and colleagues inspect pupae trays on a conveyor belt at a sterile fly facility in Mission.

USDA-National Agricultural Library

Knipling (fourth from left) and colleagues inspect pupae trays on a conveyor belt at a sterile fly facility in Mission.

USDA-National Agricultural Library

A Look Into the Future

In mid-September, a detection of the New World screwworm occurred 70 miles from the U.S. border in the state of Nuevo Leon, Mexico. The screwworm is slowly moving north, and it's hard to predict when it might arrive in Texas.

As the flies approach, TPWD and partners are working hard to get ready. When we eradicated screwworms the first time, facilities in the U.S. and Mexico bred hundreds of millions of sterile flies for release. “For a variety of reasons they were either shut down, or given back to Mexico; some of them burned down,” says Gann. “We currently only have one facility in operation — in Panama.”

The Panama facility, called COPEG, currently produces around 100 million flies a week; more fly facilities are needed for successful eradication. In June, USDA officials announced plans to modify an existing building at Moore Air Force Base near Mission into a new sterile fly facility that can produce 300 million flies a week. And in August, the USDA provided funds to convert a fruit fly breeding facility in Metapa, Mexico, into a sterile New World screwworm breeding facility.

As the U.S. readies itself for the New World screwworm, TPWD asks Texans to please report any suspected sightings of screwworm larvae to their local TPWD biologist. “TPWD will continue to train our wildlife biologists, game wardens and state park staff across Texas on New World screwworm background, sampling procedures and submission of suspected New World screwworm larva for identification,” says Gann. “We’ll keep working alongside our partner agencies on a response to a potential New World screwworm infestation in Texas and continue to be a resource for landowners, ranch managers and hunters across the state.”

For more information about the New World screwworm and TPWD's response, please visit: tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/diseases/screwworm/