The American Crown Jewels of long-distance hiking, the Appalachian Trail, Pacific Crest Trail and Continental Divide Trail, each stretch over 2,000 miles and cross multiple state lines. Although Texas is the largest state in the contiguous United States, it has never been a destination for “thru-hiking,” the sport of long-distance trekking from end-to-end on a single, continuous trail. Our lack of public land makes it difficult to create such a route.

For decades, the closest thing we had was the Lone Star Hiking Trail, deep in the Pineywoods. This joint project of the U.S. Forest Service, the Lone Star Chapter of the Sierra Club and the Boy Scouts of America was constructed in the 1960s and ‘70s. Today, it covers 96 miles of East Texas within the Sam Houston National Forest.

In 2011, the 130-mile Northeast Texas Trail took the crown of Texas’ longest trail. It runs through 19 small towns — from Farmersville, outside Dallas, to New Boston, just outside Texarkana. Unlike the Lone Star trail, which offers a traditional backcountry hiking experience, the NETT takes hikers from town to town and includes trailheads in town centers. Hikers, bikers and horseback riders can travel a few dozen miles on the trail and then stay in a hotel or grab a bite to eat in any one of the towns along the route.

Since then, many more trail projects have broken ground on innovative thoroughfares that will connect Texans — both logistically, as routes for commuters, and metaphorically, as shared spaces in the outdoors.

In this guide to the state’s regional trails projects, we’ve included trails that have upwards of 50 miles and connect major population centers. These trail projects are in varied states of completion. Some are just a skip and a hop from welcoming their first users. Others have many years and miles of hard work ahead. All are ambitious projects offering exciting possibilities to trail-loving Texans.

Paso del Norte

Maegan Lanham

Maegan Lanham

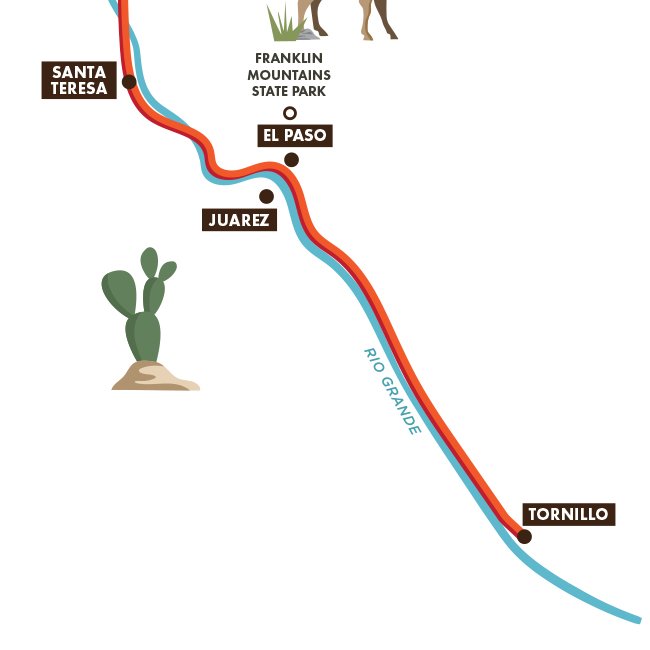

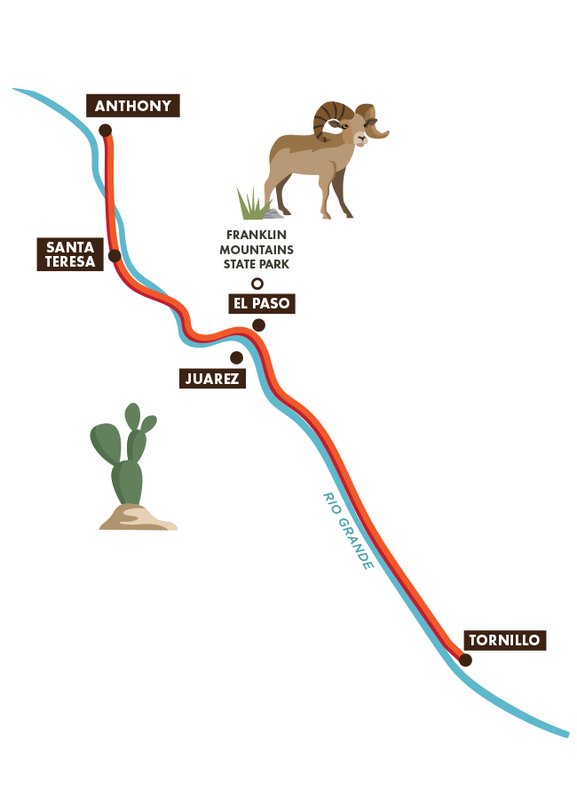

At the far western tip of Texas, this 75-mile corridor will extend from Tornillo at the southern end up to the town of Anthony, following the course of the Rio Grande. The trail will run through downtown El Paso and past the Franklin Mountains for a mix of urban and natural views as users walk, run, cycle or otherwise enjoy nature along the path.

The trail is a joint project of the Paso del Norte Health Foundation, the City of El Paso and El Paso Water. According to the foundation, 20 miles of the trail have been completed so far, including the 11-mile Rio Grande River Park Trail located in the Upper Valley neighborhood on the north side of town and the 7-mile Playa Drain Trail in Mission Valley, which runs from Ascarate Park to Capistrano Park. Another 28 miles have been funded.

Courtesy Paso Del Norte Health Foundation

Courtesy Paso Del Norte Health Foundation

Playa Drain Trail in El Paso, part of the Paso del Norte Trail.

Maegan Lanham

Playa Drain Trail in El Paso, part of the Paso del Norte Trail.

Maegan Lanham

The Final Verdict:

The Paso Del Norte will provide greatly needed hike-and-bike connectivity between suburbs in greater El Paso. Many of the trail miles will be new construction projects, making the path to completion more difficult. Much remains unclear about the precise route and progress of uncompleted trail segments, meaning El Pasoans might be waiting several years to see this entire trail come to life.

Great Springs Project

Aerial view of Austin's Barton Springs.

Rob Greebon Photography

Aerial view of Austin's Barton Springs.

Rob Greebon Photography

The Interstate 35 corridor between Austin and San Antonio is one of the fastest-growing regions in the nation. The metro region is currently home to approximately 5.2 million people. That number is expected to grow to more than 8 million by 2050. As new development expands to meet growing demand, open land is growing scarce.

Violet Crown Trail in Austin.

Sonja Sommerfeld

Violet Crown Trail in Austin.

Sonja Sommerfeld

The growing pressure to conserve lands was the catalyst behind the Great Springs Project, says project CEO Garry Merritt. In fact, the trail isn’t even the primary aim of the Austin-based nonprofit; it’s the preservation of 50,000 acres of open space. Much of land is within the recharge zone for the Edwards Aquifer, and preventing further development will help replenish this primary source of water for dozens of cities, in addition to protecting habitat for species like the endangered golden-cheeked warbler.

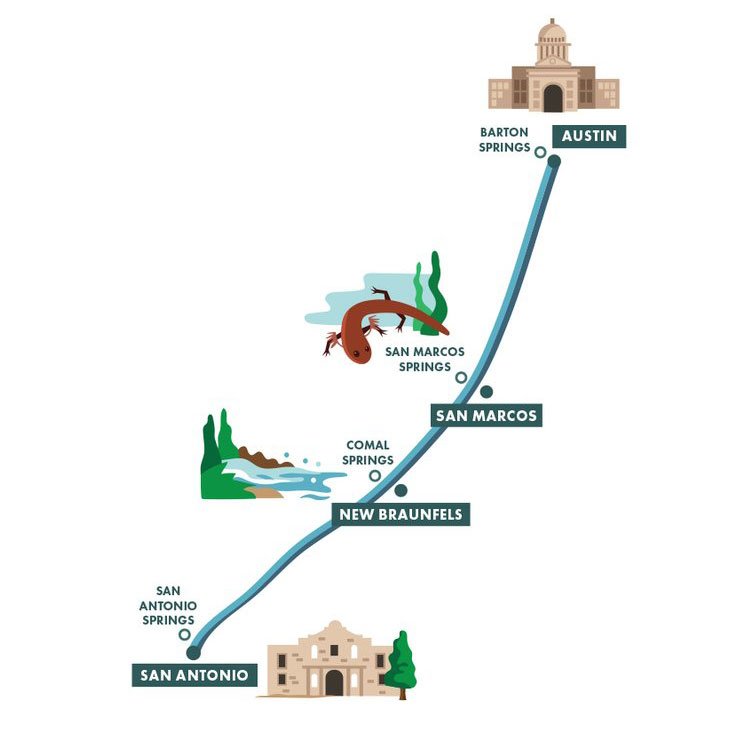

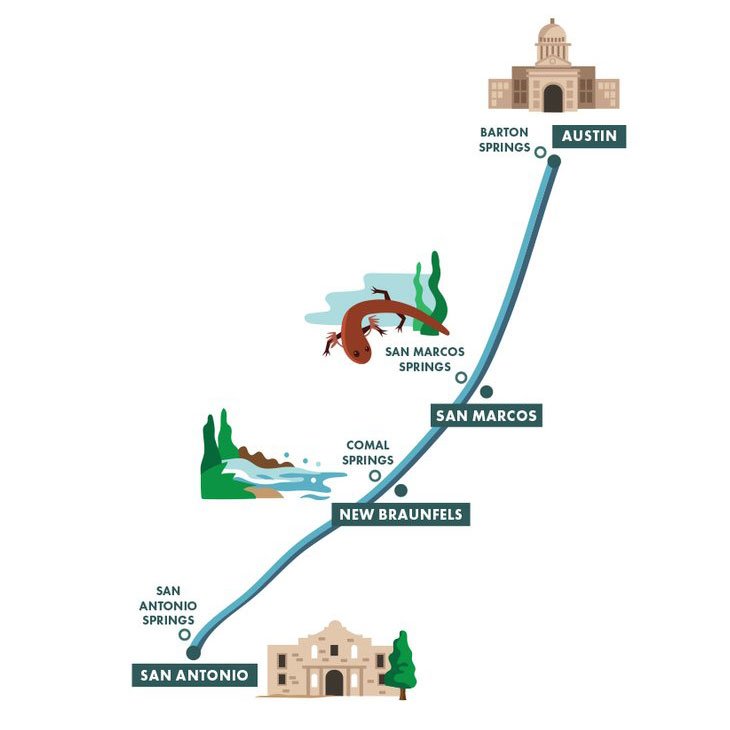

The project’s trail will extend for about 100 miles — from Barton Springs in the capital city to San Antonio Springs, the source of the Alamo city’s San Antonio River, connecting San Marcos Springs and New Braunfels’ Comal Springs along the way. Portions of the trail corridor are already complete, including much of the Hill Country Conservancy’s Violet Crown Trail in Austin, the Howard W. Peak Greenway System in San Antonio, New Braunfels’ Dry Comal Creek trails and San Marcos’ Purgatory Creek trails. The primary task of the Great Springs Project will be to connect these existing trails into one long route through land acquisitions and easements.

The Final Verdict:

It’s a tall order to link together a long-distance trail in this densely populated area, making this a costly, complicated project. The organization is currently conducting an 18-month study to identify all possible trail routes and has held firm to its goal of completion in 2036, in time for the Texas bicentennial. Although completion of the trail is more than a decade out, the Great Springs Project has gone about preparing for its final vision in a high-profile and organized manner, which has paid off in its ability to secure grant funding and public support. It may be a while, but there’s a strong probability that hikers’ patience will pay off with a beautiful and useful corridor to get around Central Texas.

xTx

Mountain bikers at Big Bend Ranch, which lies along the xTx route.

Earl Nottingham

Mountain bikers at Big Bend Ranch, which lies along the xTx route.

Earl Nottingham

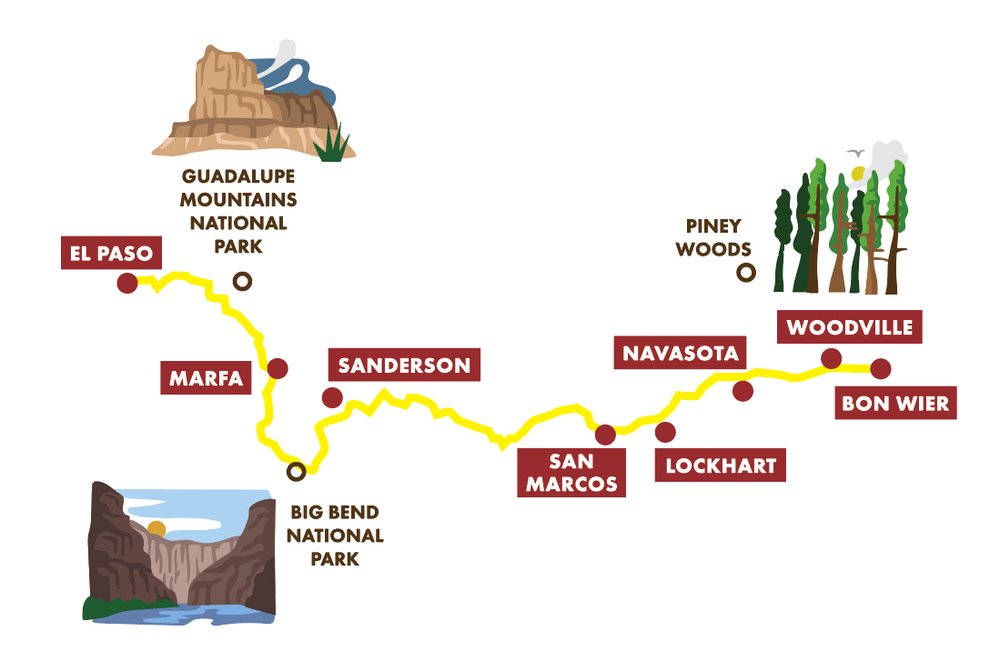

The xTx has billed itself as Texas’ answer to the thru-hiking corridors of other states. The current draft route of the xTx has the trail running for 1,550 miles across the horizontal midline of the state. It runs east to west, beginning in the little town of Bon Wier on the Louisiana border and stretching all the way to El Paso.

Trail founder Charlie Gandy says his vision for the xTx was inspired by the Arizona Trail, which runs for 800 miles through desert and pine forest. That route was forged by Dale Shewalter in the 1980s by identifying existing trails and figuring out what feasible connectors could link them together. A good chunk of the land through which the Arizona Trail passes is privately owned — 18 percent, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

The xTx faces an even greater challenge when it comes to linking together trail segments. More than 50 percent of land in Arizona is publicly owned, as opposed to less than 10 percent in Texas. To get around that problem, the initial xTx route relies heavily upon paved and gravel roads, where users will share space with vehicles.

Hikers check out an East Texas section of the xTx.

Chase Fountain

Hikers check out an East Texas section of the xTx.

Chase Fountain

The Final Verdict:

The trail receives high marks for ambition because of its massive scale, and, compared with many of the trails on this list, you’ll be able to hike the xTx relatively soon. Gandy is planning to hike the full 1,550-mile route in early 2026 and will officially “open” the trail by publishing a final route later in the year. However, even the finished version will feature few of the trail amenities that both urban and backcountry hikers expect, including signage, toilets and public campsites. Most importantly, much of the trail will lack the backcountry wilderness experience that people imagine when they think of thru-hiking. But by prioritizing speed over amenities, Gandy hopes to gather momentum for the project and then make changes to the route, including the addition of easements that will redirect the route away from traffic and adjustments that will bring the trail past private campgrounds.

Listen to an episode on the xTx trail on our podcast, Better Outside.

The Loop

Biking the Trinity Skyline Trail in Dallas.

Maegan Lanham

Biking the Trinity Skyline Trail in Dallas.

Maegan Lanham

Dallas is known for its sports teams, business culture and the State Fair. Now, the North Texas city is in the process of remaking itself as a haven for green spaces and transportation through multiple long-distance trail projects, which we’ve lumped together in this segment.

The Loop Dallas aims to use existing trails and new trails to link together a 50-mile route encircling downtown and connecting to destinations like White Rock Lake and the Trinity River Audubon Center.

Many of these existing trails have been around for years, like the popular 3.5-mile Katy Trail in the Highland Park neighborhood. Of the 11 new trail miles, nine are either under construction or about to break ground. The final two-mile stretch, part of the Trinity Forest Spine Trail, is currently in the planning stage and is slated for completion by 2028.

In addition to The Loop, several trails spearheaded by the North Central Texas Council of Governments will help transform the Metroplex into a hub for alternative transportation. Current projects include the 60-mile DFW Discovery Trail, which will connect Dallas to Fort Worth and is slated for completion next year, and the Cotton Belt Trail, a 50-mile trail that will stretch from downtown Fort Worth to Plano. Trail builders are carrying out these projects by using innovative practices such as use of active rail corridors. By constructing within active corridors, especially those created by Dallas Area Rapid Transit, these trail projects have gained access to more route options.

A neighborhood section of the Loop in Dallas.

The Loop Dallas FB

A neighborhood section of the Loop in Dallas.

The Loop Dallas FB

The DFW Discovery Trail will link Dallas and Fort Worth.

Maegan Lanham

The DFW Discovery Trail will link Dallas and Fort Worth.

Maegan Lanham

The Final Verdict:

Within the last two decades, Dallas has rapidly turned itself into a haven for hiking, biking and other trail-oriented activities through a multitude of projects. Not only are these trails large in scope, but some of them are also in advanced stages of completion. Another two decades from now, there will likely be hundreds of miles of interconnected trails in the Metroplex for recreation and commuting.

CARACARA TRAILS

The Westrail Walking Trail in Brownsville.

Courtesy City of Brownsville

The Westrail Walking Trail in Brownsville.

Courtesy City of Brownsville

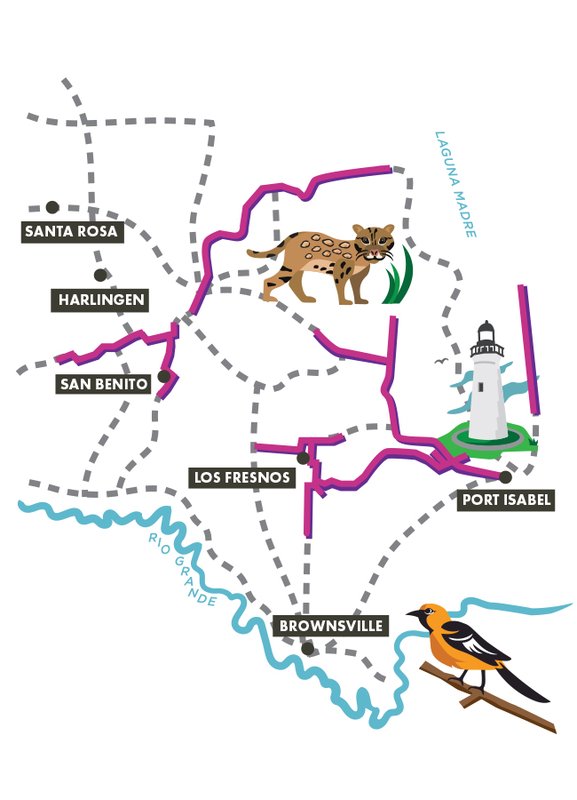

Rio Grande Valley officials and recreation advocates are envisioning a 428-mile network of multiuse and paddling trails spread across Cameron County in the southernmost tip of the state. The trail is a rails-to-trails project, meaning it’s utilizing land from out-of-commission rail corridors, and also aims to make use of the region’s extensive network of irrigation canals and drainage canals as trail corridors.

The Valley Baptist Legacy Foundation, the University of Texas School of Public Health and numerous city and municipal partners are working together to bring this vision to life as part of their “Active Plan” — a blueprint for creating a culture of health, wellness and physical activity in the Rio Grande Valley. Their mission is to use the trails to showcase the diverse ecology of the region — from beaches and wetlands to brush — and the region’s rich cultural sites to inspire physical activity among residents and to spur a regionwide “active tourism” economy.

The Final Verdict:

This highly ambitious project calls for the highest mileage of new trail construction of any on this list. Ground has been broken on some of that new construction, and some portions have been completed, such as the Historic Battlefield Trail in Brownsville. The project is in its first phase, which includes six “catalyst projects,” covering 57.5 miles of multiuse trails and on-road bicycle routes and 18 miles of paddling trails. However, the Caracara Trails have a long way to go until the final vision is realized. It will take a long time to link together these six catalyst projects. Not only does the project not have an estimated completion date at this point, but the draft trails plan hasn’t been updated in nearly a decade. Marisa Amaya, special project manager of the Caracara Trails, expects the plan to be updated later this year.

Belden Trail in Brownsville.

Cat Groth

Belden Trail in Brownsville.

Cat Groth

Hiking on the Los Fresnos Hike and Bike Trail.

Maegan Lanham

Hiking on the Los Fresnos Hike and Bike Trail.

Maegan Lanham