In 1999, four skeletons of offshore drilling rigs were dragged across the Gulf of Mexico to create an artificial reef locally known as Big Red. One of dozens on the Texas coast, the reef provides habitat for fish and coral as well as a place for divers to explore the depths of the Gulf.

More than 20 years later, I’m tagging along to the reef with three South Texas sportsmen to learn the fusion of fishing and hunting called spearfishing.

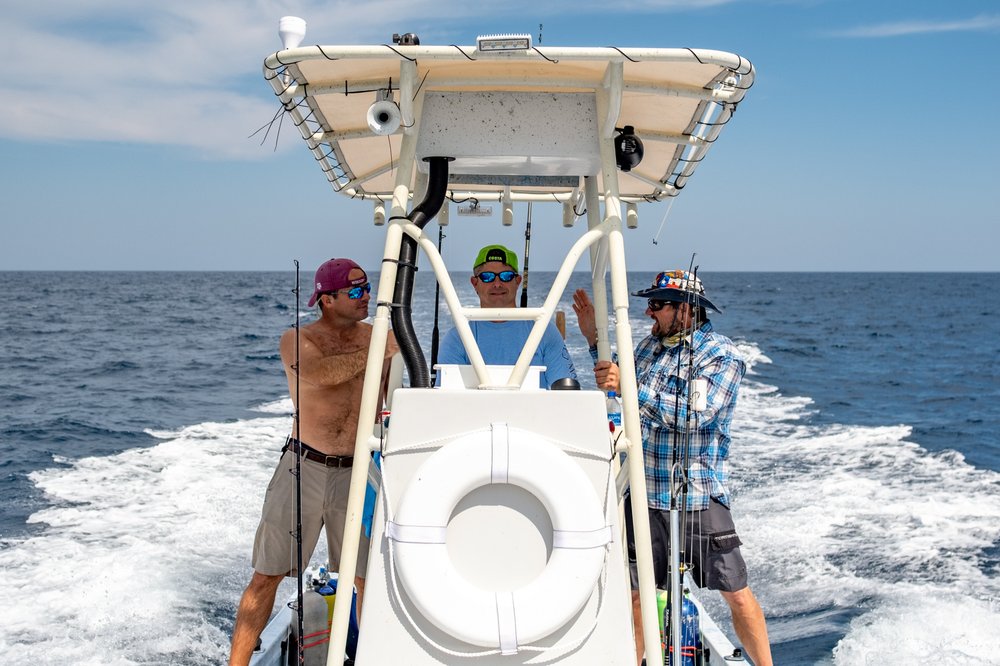

Sean Allison, a spearfisherman and scuba instructor with over 30 years of experience, stands next to veteran divers Andy Bennett and captain Matthew Downs as we cruise out of view of the Port Aransas Municipal Marina.

A hobbyist YouTuber, Sean records his dives with a GoPro and posts them to his channel, which contains dozens of videos. Most of his content is no-nonsense headcam footage, but he also has tutorials and informational videos about spearfishing in Texas saltwater.

Sean began his spearfishing career with a snorkel and a mask while stationed at Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor, where he acted as an operations specialist in the Navy.

“I still remember the excitement of potentially being able to shoot something underwater,” Sean says. “I love hunting and I love fishing ... how can it get any better than hunting fish?”

Some spearfishers choose to free-dive, holding their breath for minutes at a time. However, with the unpredictable nature of the Gulf of Mexico, it wasn’t long before Sean made the switch to scuba. While some purists believe an air tank takes the sport out of the equation, for other anglers spearfishing with scuba equipment is simply a way to stay safe.

INTO THE GULF

The Gulf of Mexico is less empty than one might expect. As brown-green coastal water gives way to beautiful blue teal, massive tankers and oil rigs dwarf our little boat. Halfway to Big Red, we approach a shrimp boat named King of the Sea.

“We always stop at these shrimp boats on our way out,” Sean says. “They have the freshest catch, and sometimes we can barter for it. If they aren’t interested, there are always fish trailing behind.”

An hour and a half of wind and ocean spray from Port Aransas, Andy cuts the throttle as we circle Big Red, officially known as the Matagorda Island-703 Reef. Our position exists solely in GPS coordinates; the depth sounder depicts a prismatic skeleton some 60 feet down.

The current and wind rock our boat. Having four full-sized humans in an area this small ensures all movements are deliberate and methodical.

Mooring the boat requires Matthew and Andy to descend to the uppermost part of the rig, tying a buoy to a length of chain. Andy and Matthew give the buoy a few yanks to indicate they’re done, and they head deeper to hunt in the rig while Sean and I don our gear.

At 33 nautical miles from port, Big Red is in the federal waters controlled by the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, the regulations of which differ from those of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Knowing your location and the rules of each entity are important.

“Not only are the seasons, bag and size limits different, but fish are even measured differently,” Sean says. “The details matter when trying to stay legal. It’s complicated.”

It takes knowledge and practice to accurately determine the legality of your prey, but the laws exist for good reason. Invasive species and commercial fishing present big enough risks; it’s a hunter’s obligation to be safe, legal and ethical.

INTO THE DEEP

Bubbles begin to break the surface as Andy and Matthew reach the safety stop on their ascent, a pause for three to five minutes at 15 feet deep. At 90 feet underwater, ambient pressure is four times that on the surface. The pressure forces excess nitrogen into the bloodstream. Safety stops facilitate venting off some of that excess nitrogen that might otherwise cause sickness.

With Andy and Matthew safely back in the boat, Sean and I prepare to roll backward into the choppy blue. Immediately upon impact, the current grabs hold; only a thin blue lifeline trailing off the bow keeps us in the same area code.

I follow Sean down our lifeline to the rig. After 30 feet, we come into view of the barnacle-encrusted frame. After 60 feet, we’re there. Most colors are washed out except for blue and green. The Gulf of Mexico is a new world, and we are there on borrowed time.

Like a wind, the current weakens as it flows through the rig. Still, Sean is forced to straddle a huge pipe to ready his spear gun. He anchors it against his chest and stretches rubber bands to the base of the spear shaft.

The reef may break up the current, but that hardly takes it out of the equation. A pillar offers temporary protection, but if I kick out into view of the open ocean, the waves of current threaten to consume me. Given the power of the water, I might as well be a leaf caught in a slow-motion breeze.

A seasoned veteran, Sean dives with a grace that comes with thousands of hours underwater. While I am struggling to control my breathing and simply survive, he is already lining up a shot.

Because water is denser than air, it is impossible to track fish with the spear gun. They are perfectly suited to the underwater world, which means spears must compensate by anticipating where the fish will be. Only after designating the species and legality of a fish does Sean take aim, hoping that the fish will continue to follow its course and that his spear will meet it with deadly dispatch.

There is a single square inch where the spine meets the skull of the fish that provides the quickest kill. In Sean’s videos it’s rare to see him miss, and in person, it’s no different. Within 20 minutes, Sean’s stringer anchored to the top of the rig is filled with gray snapper.

After ascending slowly to our safety stop, we grasp our lifeline in one hand, taking a moment to relax. The blurry, fractured shape of our boat looms overhead, but we remain in the current, our bodies drifting like weathervanes.

“It’s my escape from reality where the phone never rings and nobody bothers me,” Sean says. “I’m not a social person, and I relish the isolation from society. It’s just me exploring one of the least explored areas of the planet.”

BACK ON THE BOAT

The sun passes its peak as the men set about cleaning the fish. A deftness of movement from years of experience makes the dirty job whisk by. Without looking, Sean shears a sliver of fish, flicking it from the tip of his knife in my direction. Either out of instinct or just wanting to fit in, I pop the freshest fish I’ve ever tasted into my mouth. It’s neither warm nor cool, like the Gulf.

“It could use some soy sauce,” I say.

This is Sean’s life. Between graveyard shifts and raising his daughter, he sometimes finds a window of opportunity to go on these expeditions, even if it conflicts with much-needed sleep.

I’m exhausted from a very early 4 a.m. commute from Austin, but Sean hasn’t even seen the pillow yet today. Sacrifices like that are made only for something truly important.

“The discoveries I’ve made along the way have been life-changing for me,” Sean says. “I will do it as long as I’m physically able because it’s what I feel I was created to do. I was made for this — it’s where I belong.”