The Pain of the Spill

Our Gulf wildlife may feel the BP oil spill’s effects for years, even decades.

By Melissa Gaskill

On an early fall afternoon, sand blows along a Texas beach, sea oats wave over the dunes, and gentle green waves roll to shore. Nothing to hint at the disaster that occurred off the coast of southeastern Louisiana on April 20.

That day, the British Petroleum Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded, eventually pouring more than 200 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico before installation of a cap July 15. For week after agonizing week, oil floated in thick mats on the water, coated beaches from Louisiana to Florida and blackened grasses in marshes and wetlands.

Although tar balls showed up on the upper Texas coast in July, no significant amount of oil reached the state. Across the Gulf, cleanup crews removed visible oil from beaches and the water’s surface. The casual observer might have seen nothing amiss by summer’s end.

But thanks to the spill’s depth and volume, the toxicity of the oil and dispersant chemicals, Gulf currents and the timing of the blowout (coinciding with critical breeding seasons), the disaster is far from over. Larry McKinney, executive director of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, says we’ll feel the pain of this spill for a long time, even in Texas.

Oil on Shore

The Gulf of Mexico represents one interconnected ecosystem. Many fish, crabs and shrimp that live in Texas bays breed offshore, and their larvae spend several years in the wider Gulf. Those killed by oil won’t return here to provide food for other creatures. Oceangoing species that migrate on the Gulf’s established eddies and currents may carry oil to their predators in Texas.

Since oil reduces the productivity of wetlands and marshes, the spill likely reduced populations of many species that depend on this habitat, and, in the long term, the species that feed on them.

“Tiny animals in sediment are harvested by birds, and by crabs, which are eaten by larger birds,” says Cecilia M. Riley, executive director of the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory in Lake Jackson. “These small organisms are prey for larger fishes, too, which are then prey for many water and wading birds.”

Marsh grasses take two or more years to regrow, so birds nesting in marshes may fledge no chicks for up to three years. Birds that nest on barrier islands and beaches likely suffered great reduction in fledged chicks during the spill, and while beaches may be safe by next breeding season, these birds still face diminished food supplies and food chain disruption, which can reduce avian productivity for years.

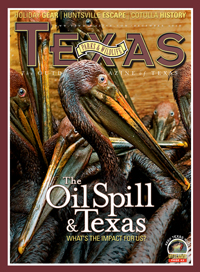

Brown pelicans, removed from the endangered species list in 2009, have relatively low reproductive rates, and the Audubon Society reports that the oil’s effects on their breeding cycle could seriously harm the population. Other coastal species at risk included roseate spoonbills, reddish egrets, black skimmers and snowy plovers.

While oil didn’t directly affect birds on the Texas coast, experts know little about the connection between populations. It’s possible, Riley says, that birds breeding in Louisiana, for example, are part of the winter population in Texas.

“We don’t know how much these birds move between states, but they are not sedentary,” she says.

Tens of millions of birds migrate through the Gulf and Texas in fall and spring. Any remaining oil will affect those migrants, as will reduced habitat and food supply.

On on the Surface

Many marine species feed at the surface, including marine mammals and sea turtles. Ingesting oil and dispersants can lead to ulcers, bleeding, diarrhea and digestion problems.

Air breathers such as turtles and marine mammals can inhale volatile chemicals from oil on the surface, causing inflammation, emphysema or pneumonia. Physical contact with oil and chemicals can irritate skin and eyes, burn mucous membranes of the eyes and mouth and increase susceptibility to infection.

Whether inhaled or ingested, these chemicals can damage organs and cause anemia, immune suppression, reproductive failure and death. Scientists observed that a number of marine animals didn’t appear to try to avoid oil from the spill, whether on the surface or in the water column.

Oil Below

The Deepwater Horizon well released oil from almost a mile below the water’s surface. The Ixtoc I blowout off the coast of Mexico in 1979 also released a huge volume, 140 million gallons, but at much shallower depths. The Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska spilled oil on the surface. This latest event created plumes of oil and oil dispersant mixtures at depth, or on the floor of the Gulf, where they could linger for years. At that depth, says Harte institute associate director Wes Tunnell, colder temperatures and lack of light mean little biodegradation and photo-oxidation of the oil.

Effects of subsurface oil are not only harder to see, but perhaps more damaging and long-lasting, he explains. Many species that live in deep water remain largely a mystery, and, therefore, so does how they could be affected.

Hard banks capped with coral reefs and teeming with fish line the continental shelf in the Gulf, McKinney says. Off the shelf, thousands of feet deep, vast forests of corals hundreds of years old support incredible biodiversity. These deep environments are sensitive to toxic effects of oil and dispersants, he adds, and to the low oxygen levels associated with the presence of those substances.

Significant amounts of oil from the spill apparently still lurk beneath the surface of the Gulf. Measurements taken by scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in late June and reported in mid-August indicated a plume of hydrocarbons, in the form of nearly invisible droplets, more than 3,000 feet below the surface and measuring 22 miles long, 1.2 miles wide and 650 feet high. Woods Hole scientists also took measurements indicating that microbe consumption of subsurface oil might be slower than expected. Researchers from the Georgia Sea Grant program estimated that up to 79 percent of oil from the spill remained in the Gulf late in the summer.

This deep oil may surface gradually, creating, in effect, a series of spills that could poison marine life and wash ashore repeatedly for months, or even years. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department scientists collected environmental samples at 21 locations along the coast in early and mid-July, says Don Pitts, director of TPWD’s Environmental Assessment Response and Restoration Program. These results and a follow-up survey will help determine how much, if any, of that oil reached Texas. Hurricanes and major storms carried the risk of pushing significant amounts of oil ashore.

Signature Species

While many effects of the oil remain to be determined, and may not be well understood for years, scientists have a pretty good idea how a few species fared.

Endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtles that hatch every summer on Texas beaches settle into drift lines of seaweed, floating with currents for a few years, according to Donna Shaver, head of Padre Island National Seashore’s Kemp’s ridley recovery project. Research indicates that it takes several months for the hatchlings to reach the eastern Gulf, so releases of clutches from Texas beaches went on as usual last summer.

However, currents could have carried some hatchlings into the oil, says Carole Allen, Gulf director for the Sea Turtle Restoration Project, which launched an unsuccessful effort to stop those releases. “While hatchling migratory paths are not precisely known, it’s understood they’re drawn to areas where oil pooled. Some of the hatchlings could have instead been taken to the Galveston sea turtle facilities of the National Marine Fisheries Service for a few months, until a safe place to release them was found.”

Based on the turtle’s known behavior, nesting females probably arrived in the southern Gulf by late spring, and did not encounter oil before nesting. However, data that Shaver has collected in past seasons shows that, after nesting in Texas, female turtles often travel to the northern Gulf. Juvenile ridleys also feed in the northern Gulf and are indiscriminate eaters, generally swallowing whatever is in the water — including tar balls.

The number of ridley nests recorded was down in 2010. Shaver reports 140 in Texas versus 197 in 2009, and about two-thirds as many in Mexico as last year. Rather than oil, the culprit was likely a severe winter that left turtles with insufficient nutritional reserves for nesting. But fewer nests this year, and possible decreases in coming years because of oil exposure, could result in a discouraging prognosis for these endangered animals.

In addition, early cleanup efforts included burning oiled sargassum, primary habitat for early life stages of fish, crabs, shrimp and other fish species as well as young sea turtles. Turtles may have burned along with the sargassum, says Harte scientist Thomas Shirley, which also could affect populations long-term.

Sperm whales migrate along the edge of the continental shelf off Texas between the southern Gulf and feeding grounds around the Mississippi River delta, the area of the spill, Shirley says. These large mammals risked exposure from breathing at the surface and feeding at depth, where they may have come in contact with subsurface oil or ingested it along with their prey. The Exxon Valdez spill caused increased mortality and decreased birth rates in orca whales, according to Heather Heenehan, a study fellow at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and sperm whales could be similarly affected.

Twenty-eight species of dolphins inhabit the Gulf, and Bernd Wursig, a marine biology professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston, says those in the spill area often cover large areas in a short amount of time, essentially ranging throughout the northern Gulf. While near-shore dolphin populations tend to be resident to certain areas, there seems to be interbreeding at boundary areas, so Texas dolphin populations could be affected. Wursig studied dolphin behavior after the 1990 Mega Borg oil spill in the Gulf and concluded that the animals can detect and avoid mousse or weathered oil, but not the more volatile sheen or slick form.

Shark species at risk from the spill include thresher, hammerhead and tiger sharks, as well as whale sharks, the world’s largest fish. These filter feeders gather around the Mississippi delta in summer, and oil could have fatally coated their gills. Whale sharks in particular will suffer from any oil-induced decline in plankton, their primary diet.

“Indirectly, we’ll see a decline in available food,” says Eric Hoffmayer, a scientist at the Gulf Coast Research Laboratory in Ocean Springs, Miss. His records of historical sightings of whale sharks show about a quarter of the total recorded fall within the oiled area. Whether that held true last summer is hard to say.

With nearly 84,000 square miles of Gulf waters closed after the spill, few people were on the water to see and report whale sharks. “We had more than 160 sightings [in 2009], and my guess is that [for 2010] we’ll be lucky to get 60,” he says. “There’s a good chance animals succumbed to the oil, but we don’t know how many, and we may never know.” Once a shark dies, it sinks to the bottom.

The Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, a series of coral reefs atop salt domes 60 to 100 feet below the surface, lies 300 miles west of the well site. While oil had yet to be recorded in the area by fall, Tunnell says the deep plume could become trapped in an eddy and eventually end up there. Filter-feeding coral can ingest oil, and ingestion or direct contact can cause death or reduced photosynthesis, growth or reproduction. Flower Garden coral spawn en masse every August, and coral larvae are particularly vulnerable to surface or subsurface oil and chemicals.

Lessons Learned

At least one good thing came from the disaster — increased awareness of the Gulf of Mexico’s importance to our nation. “The Gulf is the nation’s gas station, sushi bar and garbage disposal,” McKinney says. It provides about a fourth of the natural gas, liquid gas and oil for the U.S., and contains almost half the country’s refining capacity. These waters produce 1.3 billion pounds of seafood each year, more than the entire Atlantic coast, he says, and roughly half of all recreational saltwater fishing activity takes place here. Forty percent of the continental U.S., the entire landmass between the Rocky and Appalachian mountain ranges, drains into the Gulf.

“Whatever happens in Iowa or Kansas or Dallas or Colorado eventually comes to the Gulf of Mexico,” McKinney says. “The Gulf has been able to handle it, because it includes 40 percent of the nation’s wetlands, which are tremendous filters.”

But the Gulf already contains a 5,000- to 7,000-square-mile dead zone, created by excess nutrients in runoff. The spill likely increased its size. In the process of feeding on spilled oil, bacteria consume oxygen in the water, and oil on the surface of the water reduces the water’s ability to absorb oxygen from the atmosphere and blocks sunlight needed for marine plants to carry out oxygen-producing photosynthesis. Oil-induced wetland loss could further reduce the Gulf’s overall health.

The spill also presents an opportunity to study and learn, provided we take advantage of the opportunity.

“As time passes, the impacts will become more subtle and difficult to track. We made the mistake after the Ixtoc and Valdez spills of not following up, and we lost possible lessons,” McKinney says. “This kind of disaster will happen again somewhere in the world, and we need to be prepared. It’s critical we answer questions about the effects of this spill, and at least learn something from this enormous tragedy.” At least one good thing came from the disaster — increased awareness of the Gulf of Mexico’s importance to our nation. “The Gulf is the nation’s gas station, sushi bar and garbage disposal,” McKinney says. It provides about a fourth of the natural gas, liquid gas and oil for the U.S., and contains almost half the country’s refining capacity. These waters produce 1.3 billion pounds of seafood each year, more than the entire Atlantic coast, he says, and roughly half of all recreational saltwater fishing activity takes place here. Forty percent of the continental U.S., the entire landmass between the Rocky and Appalachian mountain ranges, drains into the Gulf.

“Whatever happens in Iowa or Kansas or Dallas or Colorado eventually comes to the Gulf of Mexico,” McKinney says. “The Gulf has been able to handle it, because it includes 40 percent of the nation’s wetlands, which are tremendous filters.”

But the Gulf already contains a 5,000- to 7,000-square-mile dead zone, created by excess nutrients in runoff. The spill likely increased its size. In the process of feeding on spilled oil, bacteria consume oxygen in the water, and oil on the surface of the water reduces the water’s ability to absorb oxygen from the atmosphere and blocks sunlight needed for marine plants to carry out oxygen-producing photosynthesis. Oil-induced wetland loss could further reduce the Gulf’s overall health.

The spill also presents an opportunity to study and learn, provided we take advantage of the opportunity.

“As time passes, the impacts will become more subtle and difficult to track. We made the mistake after the Ixtoc and Valdez spills of not following up, and we lost possible lessons,” McKinney says. “This kind of disaster will happen again somewhere in the world, and we need to be prepared. It’s critical we answer questions about the effects of this spill, and at least learn something from this enormous tragedy.”

Video clips from Texas Parks & Wildlife accompany many of the stories on this website — to see even more videos, visit TPWD’s You Tube channel