High Tide

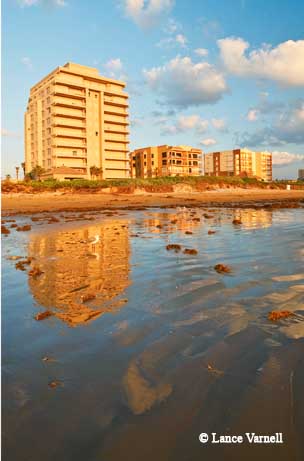

Sea levels are rising slowly but surely along the Texas coast, and scientists are trying to figure out what to do about it.

By Carol Flake Chapman

It was a calm, sunny day when I arrived at a hotel on Corpus Christi’s pleasant waterfront for the first International Conference on Sea Level Rise in the Gulf of Mexico. I glanced out at a halcyon scene of people strolling along the seawall and boats rocking gently at anchor in the marina, with a squadron of pelicans soaring by in neat formation and noisy seagulls swooping and dive-bombing their targets. In the distance, tankers were chugging their way toward the port. On such a day, the city’s strategically built breakwaters, jetties and seawall seemed as much for picturesque viewing as for protection.

Everyone, it seems, wants to live, work or vacation on the coast. More than half of the U.S. population now resides in coastal counties. And businesses and industries want to be where the people and the ports are. Around 57 percent of the national gross domestic product is contributed by coastal watershed communities.

For the scientists from Gulf-area states and from around the world gathering at the behest of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi, this quiet afternoon was the calm before the storm of information that would add some different implications and nuances to that idyllic coastal scene so common to the Gulf Coast.

As one scientist told me, “Our job is not just to see the way things are, but the way they could be.” And on the Gulf Coast, that means assessing the implications of storm surges, rising tides, subsiding land, shifting sands, diminishing marshes, disappearing wetlands and eroding barrier islands. The waters of the Gulf are rising, as measured by tide gauges. And though the current rate of sea level rise has been estimated by most measures to be around 3 millimeters a year, a little less than an eighth of an inch, model projections by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicate that global sea level rise will continue at an increasing rate during the next 100 years.

Sea level rise, or SLR as it’s known in the scientific community, is a daunting issue, fraught with a volatile combination of historic inevitability and future uncertainty. Do we need to engineer our responses, as we do in storm protection — build higher, harden infrastructure, replenish beaches, extend seawalls? Or do we need to think about adapting more flexibly and in some cases retreating?

“The purpose of the conference has been to bring together experts from different fields to see where the science stands,” said Richard McLaughlin, one of the conference co-chairs, who holds the Endowed Chair for Marine Policy and Law at the Harte institute. “Then we can think about bringing the science into decision-making. We need to talk about the physical and biological dimensions of the problem, about the human dimensions, and then finally about planning and policy. At the end of the conference, we’ll have a better idea of how coastal managers can develop tools for coastal adaptation.”

BACK TO THE FUTURE

Sea levels have been considerably higher in the distant past, as anyone knows who has picked up a fossilized seashell along an inland creek bed. And they’ve been a lot lower, too, as the Harte institute’s Richard A. Davis pointed out in the first presentation of the conference, which traced the history of the Gulf back to its origins 150 million years ago.

“Sea level has ranged from about 40 meters above its present position to 130 meters below it,” he said. The current configuration of the coast, with its deltas, estuaries and barrier islands, developed recently — over the past 7,000 years.

Currently, said Davis, we’re in an “interglacial” period, a time when sea levels rise. This is the first time, however, as another scientist pointed out, that humans have been around to react when seas were rising. Until the past few decades, sea level had been rising very slowly, about 1.5 millimeters a year. More recently, tide gauges have shown that rates of rise have doubled. Moreover, Davis pointed out, there are several areas along the Gulf where natural and human factors have caused rates of rise up to 10 mm (slightly less than half an inch) a year.

The most dramatic changes along the Gulf have been occurring in southern Louisiana, and not just because of storms like Katrina and Rita, according to Harry Roberts, former director of the Coastal Studies Institute at Louisiana State University’s School of the Coast and Environment. Roberts caused a stir last year with a report in the journal Nature Geoscience on his findings about the fate of the marshes and wetlands associated with the Mississippi River delta, and his presentation to this conference was no less glum. Largely because of the multitude of dams built upriver, he said, the Mississippi no longer carries enough sediment to replenish the landmass being lost. As the waters rise and the land subsides, Roberts predicts, the “drowning of a large part of the Mississippi River delta plain is inevitable.”

Though Roberts was presenting a worst-case scenario, other scientists were focusing on the effects of even a small rise in sea level on the marshes and wetlands that are crucial buffers, transition zones and marine nurseries along the Gulf Coast.

Roger Zimmerman, laboratory director of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Service in Galveston, pointed out that fisheries production in the Gulf is largely dependent on estuaries. The Gulf’s harvest of shrimp, he said, is the nation’s second most valuable fishery, while catch of Gulf menhaden is surpassed in volume only by Alaskan pollock. As wetlands fragment and convert to open water, said Zimmerman, they temporarily increase in value for many fishery species, including shrimp, because of an increase in edge habitat. Ultimately, however, wetland loss will result in losses to fishery populations dependent upon these habitats, including shrimp, crab, red drum and spotted sea trout.

John Jacob, the director of the Texas Coastal Watershed Program who also works with the Texas Sea Grant College Program, said that the only way that most of the estuarine wetlands of the Texas Gulf Coast can keep up with accelerated sea level rise is essentially by moving inland, which he called “wetland transgression to higher ground.” However, the ability of marshes to migrate inland depends, he said, on the coastal topography such as slopes and bluffs as well as human development that stands in the way.

THE UNCERTAINTY FACTOR

The key word that kept recurring during the conference was uncertainty. Uncertainty on the part of scientists on exact numbers. Uncertainty on the part of coastal dwellers and coastal managers of how to respond to an uncertain future. It’s a word that has put some scientists on the defensive, particularly with regard to climate change, and most of the experts attending the conference preferred to talk about clearly observable sea level rise without debating causes and without conjoining sea level rise with projections of climate change.

Some scientists did, however, address the subject of the frozen elephant in the room — the vast, melting glaciers of Greenland and the Antarctic, whose potential contribution to sea level rise is ominous but difficult to pinpoint. “Ice is the ‘gotcha,’” said one scientist.

British scientist David Vaughn, who has been studying glaciers for the British Antarctic Survey and who is an author of the most recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, said that he was going to stick his neck out with a prediction of sea level rise that he felt was conservative. His personal projection of sea level rise in coming decades, he said, was a rate of 4 to 6 mm a year, with an increase over the next 90 years between 40 and 140 cm — that is, between 15 inches and 56 inches. The great variable, of course, is the ice sheets.

Scientists David Yoskowitz and James Gibeaut created a model for what different levels of sea level rise would mean for the Galveston region. For Galveston County, a 27-inch rise along with a Hurricane Ike-level storm would displace 78 percent of the current households, under their projections. With an Ike-level storm on top of a 59-inch rise, 93 percent of households would be displaced.

For scientists like Larry McKinney, the former director of the Coastal Fisheries Division for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department who now heads the Harte institute, the harbingers of change can be observed closer to home. McKinney, who lives on the shore near Corpus, has noticed changes in the kinds and numbers of fish in the waters near his home.

“Corpus is right on the cusp of what’s happening,” he said. For example, there was the school of 200 mango snapper — a semitropical species — he observed in nearby waters. McKinney also spoiled a little of the thrill I had felt a few years ago at catching what I thought was a rarity — a snook — on my first cast from a jetty on South Padre Island. Snook, too, he said, are becoming more abundant in the area, while flounder are disappearing and reappearing in areas farther up the coast.

McKinney pointed to data collected by TPWD’s Coastal Fisheries Division, possibly the largest database of its kind in the world. Water temperatures are among the millions of data points generated over the last three decades of continuous resource monitoring.

“You can look at 30-year trends in water temperature,” he said. “While the summer temperatures are not hotter, the winter water temperatures have warmed up at a pace that fits the global model.”

TOMORROW’S HIGH TIDE

Part of the problem for coastal managers and decision makers in responding to changing conditions in the Gulf, some scientists suggested, is that those changes may seem so slow or gradual as to be almost unnoticeable, except in the extreme cases of storm surge that reveal coastal areas of greatest vulnerability. When the edges of Hurricane Ike swept over Galveston Island, for example, the surging waters followed the patterns that Gibeaut, who heads the Coastal and Marine Geospatial Sciences program for the Harte institute, had predicted on a hazards map he had prepared for the city.

“We know how barrier islands work,” Gibeaut said, “and we have been collecting data on Galveston Island for decades.”

But how does that dramatic one-time encroachment compare to waters that are slowly but inevitably rising less than half an inch a year — particularly when rising sea levels are a challenge humans haven’t faced before?

“Never before in human history have humans been faced with a period of significant sea level rise,” said Michael Orbach, who directs the Coastal Environmental Management Program at Duke University. “We lack the legal and policy tools to deal with true inundation, as opposed to hazards and storm events. You can make things better after a storm. But inundation is a very different problem. Things cannot be put back the way they were before.”

Margaret Davidson, who directs the Coastal Services Center for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, suggested that one way to present the situation to the public would be to declare, “Today’s storm surge is tomorrow’s high tide.” But she acknowledged that for those who have experienced the brunt of storms like Ike and Rita, such a notion may be simply too overwhelming to contemplate, particularly when another such extreme high-water scenario may be decades away. Or less than a year away.

Davidson suggested that sea level rise might be better approached in increments. Instead of trying to tackle the whole rising sea problem, she said, perhaps we should plan for a series of flooding events or seasonal storms that will progressively worsen in magnitude over time.

After all, said one scientist, “Sea level rise is happening. But it’s not going to be a wall of water. It’s going to be day by day — inexorable and inevitable.”