Nurturing Nature

Master Naturalists volunteer their time to conserve and educate.

By Sheryl Smith-Rodgers

The man hadn’t meant any harm. He’d simply found three horned lizards last April while working in West Texas and carried them home to Wichita Falls to show his kids. Naturally, they’d oohed and ahhed over the spiny reptiles. But then the family didn’t know what to do with the trio. Nor were they aware of state wildlife regulations that prohibit the possession or transportation of the threatened species without a special permit.

When news of the problem reached Texas Master Naturalists with the Rolling Plains Chapter, an official partner in the state’s Horned Lizard Watch program, several offered to help. Three days later, two specially trained volunteers hit the road and headed west with the lizards safely aboard their vehicle.

“Those Master Naturalists didn’t take the easy way and try to find a zoo that would take the lizards,” says Lee Ann Linam, a wildlife biologist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. “Instead, they educated others about the drawbacks of releasing the reptiles outside their original habitat, researched to find out where the lizards had lived originally and then drove them 350-plus miles back home.”

“They even fed harvester ants to the lizards along the way,” Linam adds. “Those volunteers represent the best of the science, education and volunteerism that characterize a Texas Master Naturalist.”

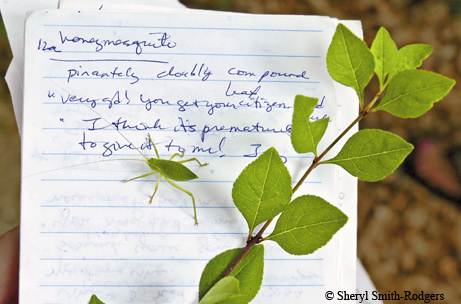

Notes on nature.

Sixteen years strong

From relocating horned lizards to removing invasive plants and leading nature walks, Texas Master Naturalists work to conserve natural areas in their regions and share their knowledge with others. Toward those goals, these dedicated folks spend hours in classroom and field training and volunteer in their communities.

Initially, the Texas Master Naturalist program — the first of its kind in the nation — emerged from a meeting in June 1996 with staff from the San Antonio Parks and Recreation Department and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Urban Wildlife program. Their idea: Why not develop a program similar to Master Gardeners but with a focus on nature?

Eight months later, 19 volunteers took the first Master Naturalist training in San Antonio, forming the founding Alamo Area Chapter in 1997. Sixteen years later, more than 7,300 volunteers have been trained through the Texas Master Naturalist program, cooperatively sponsored by TPWD and Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. Similar naturalist programs have since spread to more than 25 states.

In Kerrville, statewide coordinator Michelle Haggerty with TPWD has overseen the program since 1999.

“We only had three chapters when I started,” she recalls. “Now we have 44 chapters with another one in development. Over the past 14½ years, volunteers have contributed more than 1.76 million hours of service, which has an estimated economic impact of more than $34 million. Master Naturalists have also impacted or conducted projects on roughly 190,000 acres of habitat and developed or maintained some 1,622 miles of interpretive trails. That’s a tremendous contribution to our state’s natural resources and their future!”

Willing to work

An eagerness to learn, help and educate draws people of all ages into the Texas Master Naturalist program. Participants can be as young as 18, and many are in their 80s. The majority of members range between the ages of 40 and 59.

Lottie Millsaps of San Antonio, 82 and a “naturalist by nature,” is a charter (and still active) member of the Alamo Area Chapter. Once a month, she helps tend the Texas Master Naturalist Wildscape Demonstration Garden on the San Antonio River Walk.

Lottie Millsaps.

“The program has enriched my life so much,” Millsaps says. “It offers me so many opportunities to get outside and learn.”

In Arlington, Hester Schwarzer, 75, joined the Cross Timbers Chapter in 2002 while still working as a schoolteacher.

“Being in nature adds a dimension to your life that you can’t get any other way,” says Schwarzer, who’s since retired. “Sadly, we have a generation that doesn’t connect with nature. I’ll never forget the look of pure fear that came over a little boy’s face when a blue butterfly landed on his sleeve at the Fort Worth Botanic Garden. He should have been thrilled!”

Ben Taylor, who’s a senior at Texas State University in San Marcos, would have been. Now 22, he was raised to appreciate nature and was among the youngest members of his 2012 Master Naturalist training group with the Hays County Chapter.

“I wanted to add to my knowledge of the area and supplement what I’m learning in school,” says Taylor, a geography major. “Now that I’m certified, I’m going to share my experiences in the program with my friends and encourage them to participate, too.”

Paul and Mary Meredith at the coast.

Service across the state

Along the Texas coast, Paul and Mary Meredith of Victoria, members of the Mid-Coast Chapter, monitor invasive beetles for the U.S. Forest Service and count phytoplankton species (such as red tide) in water samples for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. They’ve also tagged birds at the Welder Wildlife Refuge and volunteered with the Sea Turtle Recovery Project on Matagorda Island.

“In the spring, we patrolled 25 miles of beach, watching for Kemp’s ridley females who came ashore to lay their eggs,” says Paul, 68. “When we found turtle tracks to a nest, we radioed the professional staff, who then came and recorded data and collected the eggs.”

Northeast of Dallas, the Blackland Prairie Chapter has partnered with the Wylie Parks and Recreation staff to restore 50 acres of blackland prairie at the Wylie Municipal Complex. Since fall 2011, the land has not been mowed so that native grass species can return. Cottonwoods, willows and other woody plants have also been removed.

“So far, we’ve seeded 11 pounds of native grass seeds,” says member David Powell, 68. “Our goal is to harvest our own seeds so we don’t have to buy them. We’ve also created a half-mile trail through the area that will include marked plots of 11 different grass species.”

In the Kerrville area, members of the Hill Country Chapter offer a free Land Management Assistance Program. Since 2005, specially trained volunteers have offered management advice to landowners who collectively own more than 27,000 acres. They’ve also surveyed plant species for the landowners.

“This program is very important because so many of the owners did not grow up on the land here,” says member Priscilla Stanley, 65.

Valeska Danielak, also with the Hill Country Chapter, is among 24 Master Naturalists who volunteer at Old Tunnel State Park south of Fredericksburg. From May through October, visitors gather at the site to watch millions of Mexican free-tailed and cave myotis bats emerge at dusk from an abandoned railroad tunnel.

“As volunteers, we collect fees, explain viewing options, talk about the bats and answer questions,” says Danielak, 43. “We help raise awareness about bats and how beneficial they are.”

Out west, naturalists with the Tierra Grande Chapter — which stretches across Brewster, Jeff Davis, Presidio and a portion of Reeves counties — volunteer at state parks and many other natural sites in the Big Bend region. For example, they’ve assisted in the search for rare Hinckley oaks at Big Bend Ranch State Park, and they maintain a native plant garden at Balmorhea State Park.

“We’re also working to improve a pollinator garden and two bird feeder stations at Davis Mountains State Park,” says member Pamela Pipes, 45.

Bird and wildlife watchers around the globe can thank the Rio Grande Valley Chapter for funding a bird feeder video camera at the Sabal Palm Sanctuary in Brownsville.

“People love to watch our birds online,” says member Virginia Vineyard, 63. “We get comments from all over the world!” (sabalpalmsanctuary.org/feedercam)

Mark Hassell at Palo Duro.

Way up north, bird watcher Mark Hassell — a Master Naturalist with the Panhandle Chapter — leads monthly bird walks at Palo Duro Canyon State Park, where he also works as a resources manager.

“It’s important to pass on knowledge and talk to kids and adults about nature,” says Hassell, 56. “We’ve got to get them outside, no matter whether it’s a state park or their neighborhood park.”

Speaking of kids, the Good Water Chapter in Williamson County is one of several that have started Junior Master Naturalist programs. Targeted at fourth- through sixth-graders, the bimonthly classes and field trips focus on amphibians, wildflowers, butterflies and other nature topics.

“We’re taking every advantage we can as a chapter to teach children about our natural world,” says member Mary Ann Melton, 60, of Hutto. “It’s been fun to watch the kids get excited as they learn.”

A high-tech native garden representing the state’s 10 ecological zones piques students’ curiosity about nature at Heritage Elementary School in Highland Village, north of Dallas. The interactive project — jointly developed by school staff and Master Naturalists with the Elm Fork Chapter — incorporates iPads with school curriculums and wildlife information produced by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

“We couldn’t have done the Texas Our Heritage Garden without the expertise of our Texas Master Naturalists,” says principal Toby Maxson. “They’re very generous with their time, and they don’t expect anything in return. They’re also very passionate about nature and educating kids.”

Learn, educate and volunteer — that’s what Texas Master Naturalists across the state do best. And back at home in West Texas, three horned toads would definitely agree.

Sheryl Smith-Rodgers.I did it. You can, too!Nature has always fascinated me. So a few years ago, when I heard about the Texas Master Naturalist program, I thought, “Wow, that’s something I’d like to do when I’m not so busy.” Then in December 2011, I found out that the Highland Lakes Chapter in Burnet had one slot open in its upcoming class. Could I commit the time? Yes! For 10 weeks, 19 fellow trainees and I met for Thursday classes at different locations in our area. We studied hydrology at Jacob’s Well near Wimberley and learned about invasive zebra mussels at the Inks Dam National Fish Hatchery. We bird-watched at Pedernales Falls State Park, hunted invasive plants at Blanco State Park and peered at metamorphic formations at Inks Lake State Park. Noted experts led many of our classes. Conservationist J. David Bamberger told us how he restored his overgrazed ranch into prime wildlife habitat. Brian Loflin, who co-authored Grasses of the Texas Hill Country: A Field Guide with wife Shirley, led us on a native grass walk at the Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge. Wildlife biologist Ricky Linex with the Natural Resources Conservation Service explained the importance of healthy creeks and watersheds. On the volunteer side, I counted birds during Project FeederWatch, pulled invasive bastard cabbage at Blanco State Park and helped with a third-grade outdoor event at the state park. By May, I completed both my training and volunteer service requirements, which meant I could wear the official badge of a Texas Master Naturalist. Even though I’m done with basic training, I’ll continue to do my volunteer and advanced training hours each year to maintain my certification status. What’s more, I’ll never stop learning about our state’s natural resources or sharing my knowledge, in hopes of inspiring others to become Master Naturalists. Want to become a Master Naturalist?People 18 years of age and older may apply for training with a Texas Master Naturalist chapter in their area. Initially, volunteers must: • Go through an approved training program that includes at least 40 hours of instruction in both the field and classroom. Plus, undergo eight hours of advanced training and perform at least 40 hours of community service. • Complete the advanced training and community service hours within one year of basic training to become certified. • Every year thereafter, complete eight hours of advanced training and 40 hours of community service to maintain certification as a Texas Master Naturalist. For more information and to find a chapter near you, go to txmn.org. Texas Master Naturalist program mission: To develop a corps of well-informed volunteers to provide education, outreach and service dedicated to the beneficial management of natural resources and natural areas within their communities. — Sheryl Smith-Rodgers

|