Reeling it in

Communities like Port O’Connor win big when fishing tournaments come to town.

By Larry Bozka

Anyone who’s even vaguely familiar with the Texas coast knows that Port O’Connor is the epitome of a “sleepy little fishing village.” Anyone who isn’t need only enter the

outskirts of town to figure it out.

The signs are everywhere.

After carving an arrow-straight path through miles of mostly featureless prairie and just before dead-ending at Matagorda Bay, Texas Highway 185 makes a final dramatic statement. A curiously divergent gallery of road signs suddenly appears to the left.

It’s an intriguing exhibition of local commerce and deeply rooted culture, a fusion of contrasts, textures and materials so eye-catching and compelling that it could arguably pass muster as an exhibit of contemporary art. Part Andy Warhol’s iconic soup cans, part Winslow Homer’s ivory-crested seas and part Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s flamboyant outdoor creations, all the way down to color-drenched fabric, the elements are dissimilar but unmistakably connected. It’s an enigmatic cornucopia of choices, presented to visitors upon arrival.

Just off the shoulder, a piggybacked cluster of panels directs passers-by to an RV park, a cabin rental facility, a motel and charter boat operation and a fishing lodge. On the ground, a black-and-white poster tacked to a stake carries the name of a fishing rod repair shop.

Two larger signs stand out in the crowd at an adjacent intersection. The bottom one features a grizzled old captain at the helm of his boat. Draped in a slicker and holding the wheel, he guides weary travelers to a motel just a short distance down the street.

The top sign promotes a restaurant. A broad swath of blue runs through its center, with three words in big white letters.

FISHING. FOOD. FUN.

There you have it. The three key commodities of Port O’Connor, presented in a message so concise it makes a message tapped out in Twitter look like a chapter of a novel.

Perhaps they could have added “tournaments” to the trio, because across the Texas coast, in some form or fashion, long established or new, tournament fishing is deeply engrained with the sport. But to the businesses they benefit, fishing tournaments are far from a bonus. They’re the key to survival, especially in a challenged economy.

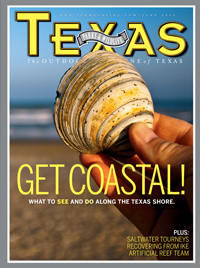

It’s a busy weekend in Port O’Connor as boats set off in search of big fish in the annual Poco Bueno Fishing Tournament.

An active base of businesses, most small to medium-sized and nearly all locally owned, work every day they can to keep their doors open in Port O’Connor, population 1,253. “Every day they can” currently translates to “from Easter to Thanksgiving.”

The town’s promoters desperately want to expand that time frame. Off-season visitors have plenty to do here, from combing the shores of area beaches to enjoying a huge range of wildlife.

That’s not the focus for a few days each July, known as the “Weekend of Poco.”

The Poco Bueno Fishing Tournament, 100 boats strong in both inshore and offshore divisions, has come again to Port O’Connor.

The exact meaning of “Poco Bueno” is still up for debate, even among the family of the late Walter Fondren III, who continue to run the tournament today. The loosely translated version is “It’s sort of OK.” The Poco Bueno Fishing Tournament is “sort of OK” to Port O’Connor in the same way that the Super Bowl is “kind of cool” for the city that hosts it.

Fondren founded Poco Bueno in 1969 when 13 teams of fishermen, all good friends, received and accepted what quickly became the most coveted invitation in billfishing. To this day, Poco remains an exclusively invitational event.

There’s no other tournament like it.

In Port O’Connor and every other community of note between the Sabine and Rio Grande, dozens upon dozens of fishing tournaments large and small aggressively vie for the prime weekend calendar slots of warm-weather months. Some are Texas traditions, wide open to all who pay the entry fee. Smaller towns hold more modest contests, often with ancillary activities that collectively make up a festival or fundraiser.

Some are venues for semi-pro anglers, experienced saltwater fishermen with an innate and insatiable bent for high-stakes competition. It’s an uncertain game, played inside the boundaries of the state’s major bay systems by a singular segment of fishing society that’s willing to part ways with money.

Again, much of it flows directly into the coffers of local businesses. With each progressive leg of every tournament series there’s a grateful community with a guaranteed economic win. The total amount of revenue that coastal contests generate is impossible to tally with any degree of accuracy.

There are boat-owner tournaments, fundraising tournaments and a growing number of “in-house” tournaments, corporate events that until recent years never went beyond the 18th hole of a country club golf course. There is no such thing as a standard format for Texas saltwater tournaments.

Here in Port O’Connor, business owners can be certain of only one incontestable fact: Poco Bueno inhabits a league all its own.

A billfish boat that gulps 50 gallons of diesel fuel an hour isn’t exactly a tea-sipper. Throughout the rest of the week, tanker trucks will roll in daily to replenish the tanks of area docks. During Poco, a boat with that kind of thirst is only one of many.

Meanwhile, at the gas pumps outside the Speedy Stop, the bay boats of Poco’s inshore division are demanding drinks of their own. The locals laughingly call this place “the mall.” While drivers await their turns at the pump, passengers walk into the store to check out the hardware.

An entire wall bristles with saltwater lures. Here at the mall, experienced customers don’t do much window-shopping. If they want a specific plug or spoon, they rattle off a model number and the person behind the counter knows exactly what it means.

Up the road, a striking banner of red-on-yellow vinyl marks the entrance to a car wash. There’s a waiting line here as well. Make and model notwithstanding, every vehicle on the lot is identical in one important way. Every one’s a pickup. And behind every one there’s a bay boat.

The car wash is a microcosm of Port O’Connor in July, and owner Leah Griffin is determined to see it expand. An unflagging town booster, Griffin came here to stay two decades ago. Today she looks after her 90-year-old mother, sells real estate and, along with business cohort Brett Williams, a tech-savvy transplant from California, runs the Port O’Connor visitors center.

Griffin’s father, the late Lee Richter, was a legendary angler with a noteworthy name both in and out of Port O’Connor, where he relocated in the 1960s to build custom flounder boats. Having seen Port O’Connor through his eyes, an unvarnished assessment of all that it is and all that it offers, she has a fondness for the area that goes beyond sentimentality.

Just off the porch of the visitors center, tropical reef fish with thin yellow flanks of onion-skin paper swim behind kite strings in the damp summer air.

“Twenty years ago, four or five fishermen would visit Port O’Connor for a ‘guy’s’ trip,” she says. “Now, the same fishermen are bringing their wives and children, passing along the art of fishing.”

Ryan Smith, 18, caught the biggest fish at 2012’s Poco Bueno.

At the end of a long day of fishing, Ryan Smith, an overjoyed angler from the small town of Portland, stands next to a blue marlin for photos. The marlin’s more than 9 feet long, and it’s just a tad shy of 500 pounds. The victorious crew wins more than $900,000.

For Smith, only 18 years old, it’s the biggest thrill of his life, something he will remember and talk about forever.

Between fishing, food and fun, there are nonetheless things that will always be priceless.

Related stories

Legend, Lore & Legacy: Walter Fondren III

3 Days in the Field: Adrift in Seadrift