New View of a Sunken Ship

Technology provides a dramatic look at a largely forgotten Union steamer off Galveston.

By Rae Nadler-Olenick

On Jan. 11, 1863, the iron-hulled USS Hatteras — a sidewheel merchant steamer retrofitted as a Union warship — sank 20 miles off Galveston, bested by the Confederate battle cruiser CSS Alabama in a fierce battle lasting only 13 minutes. Though the conflict was brief, the Hatteras’ defeat that winter night had far-reaching consequences.

When the Alabama unexpectedly appeared at 2 p.m. — visible from Galveston as an unknown speck on the horizon — the city, which had just shaken off federal occupation, stood in peril of being retaken. A Union fleet stationed off the coast prepared to recapture the Confederacy’s most important port as a prelude to a major 20,000-troop land invasion. The sinking of the Hatteras — quickly outmatched by Alabama’s superior design and firepower — put that ambitious plan on hold, giving Galveston time to build the defenses that would keep it in Confederate hands throughout the remainder of the war.

“Unlike the other large southern states, Texas never experienced an invasion of its interior,” says historian Ed Cotham. “Texas came out of the war supercharged; Galveston and Houston became major cities almost overnight postwar because they had managed to survive the war and could focus on the commercial side when things cleared up. The Hatteras had enormous ramifications for the way Texas and this entire part of the Gulf developed.”

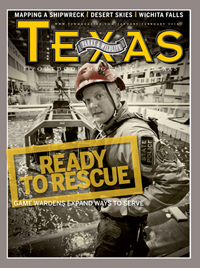

The USS Hatteras and CSS Alabama battle off the coast near Galveston.

The ship’s saga continues today.

On Sept. 9, 2012, a world-class team of 31 experts from six states and all three coasts gathered at Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary headquarters in Galveston, on a quest to unlock the Hatteras’ secrets using current technology. The participants included divers, scientists, archaeologists, historians, boat captains, photographers, students, media and even a priest. Over the next three days they would employ BlueView, a cutting-edge, ultra-high-resolution three-dimensional sonar system to map the historic vessel with unrivaled accuracy.

“That was the centerpiece of the expedition: to create a topo of the seabed, a 3-D digital mosaic,” says James Delgado, who orchestrated the complex project and is director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Maritime Heritage Program.

An overview of the USS Hatteras wreckage was assembled from multiple BlueView sonar scans.

The exercise was more than a mere accumulation of data to be filed away in nautical archives. It also incorporated a memorial service to two seamen killed at their stations in the Hatteras engine room, the battle’s only fatalities. Delgado considers the human side of the Hatteras story as important to our understanding as its technical details.

“I believe that if we scientists do our work in a vacuum, we’re not really doing our job,” he says.

To him fell the herculean task of negotiating the roles of the multiple interlocking federal and state agencies, corporate entities, foundations and educational facilities that contributed to the project’s success. NOAA, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, the Texas Historical Commission, Northwest Hydro, Teledyne-BlueView Inc., Tesla Offshore LLC, the Oceangate Foundation (now ExploreOcean), the Edward E. and Marie L. Matthews Foundation and Texas A&M University at Galveston all brought resources to the table.

The USS Hatteras’ modern-day history began in 1975–76, when Rice University space science professor Paul Cloutier and companions located it during a winter of searching with a magnetometer (iron-detecting instrument) he designed. The group retrieved a few artifacts, and Cloutier, believing the find to be beyond both state and federal jurisdictions, applied for salvage rights. The Navy denied his claim. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in January 1977.

During the ’80s and ’90s, federal archaeologists and the Texas Historical Commission reassessed the spot several times in the course of their duties as protector of national oceanic historic sites. But for the most part, the Hatteras, the only battleship sunk in the Gulf during Civil War combat, lay quietly unnoticed save for fishermen vaguely aware of “something big” down there.

In 2003, underwater photographer Jesse Cancelmo and three fellow divers obtained the GPS coordinates and set out to investigate the wreck. They found the Hatteras at a depth of 57 feet, almost totally buried, with only small parts of the paddlewheel hubs and engine exposed. Cancelmo documented what was visible, and moved on.

In 2010, he learned from a dive boat captain that 2008’s Hurricane Ike had carried away several feet of sand and silt, uncovering more of the wreck, and that Tesla Offshore divers had recently surveyed it for the BOEM.

“I thought I’d like to go back and see for myself, get some photos,” he says.

Divers take notes and explore the wreckage of the Hatteras.

The thought lay dormant until the following year, when he and Delgado of NOAA chanced to meet at a Galveston historical event and discovered a mutual passion to study the Hatteras. Delgado returned to his Washington headquarters and began lining up support.

The team gathered in Galveston in September 2012 to pick up the thread of the ship’s history. They faced a busy agenda. For those directly involved with the showcase BlueView survey, it meant two days of rigorous field work under tight scheduling. For others, it offered a rare hands-on learning experience under expert guidance: opportunities to monitor equipment, pilot the boat and even take part in the release of endangered Kemp’s ridley sea turtles that had been rescued and rehabilitated.

“There were a lot of moving parts,” observes Emma Hickerson, Flower Garden Banks research coordinator and dive supervisor, aptly describing a mission that encompassed three dive boats and some 15 divers entering and leaving the water at different times on their varied tasks, as well as a sizable contingent of nondiving personnel.

The research vessel R/V Manta, the Flower Garden Banks’ 82-foot jet propulsion catamaran, served as base for the BSEE/BOEM divers assigned to operate the BlueView equipment and for others directly involved in topside support. Others aboard included Father Stephen Duncan (an Orthodox Catholic priest), students, historians, ExploreOcean representatives and media — plus 10 turtles.

Technician James Glaeser briefs divers on how to position the BlueView sonar.

Two chartered dive boats, the 42-foot Island Girl and 37-foot Carolyn Jane, transported divers and other participants.

The expedition launched officially with the early morning departure of all three boats from their respective docks for a rendezvous at the Hatteras. Returning turtles to the Gulf, one by one, took place along the way, a hopeful prelude to the work ahead.

“Releasing the sea turtles was great, especially knowing that they have a better chance now,” says budding marine scientist Ella Barwick, 14, a veteran of A&M’s summer Sea Camp program.

Upon arrival in the vicinity of the wreck site, Manta divers first eyeballed its location and set a marker float. Later, following anchorage, they confirmed the position with sector-scanning sonar.

Father Duncan then proceeded to conduct a brief service for the lost Hatteras crewmen, John Cleary and William Healy, both Irish immigrants. Although genealogical research failed to locate relatives of either, the remembrance — capped by the placing of a wreath on the waters — brought closure to the story of two men who died fighting in the conflict.

Following the memorial, divers from the two charter boats conducted a series of setup tasks. They marked the position more precisely, assessed visibility/current conditions and ran guide lines lengthwise and crosswise over the structure.

Manta-based divers next took over to deploy BlueView. The system consists of a 3-D ultra-high-definition sonar unit mounted on an aluminum tripod with a video communication cable connected to an on-deck computer. Rotating two-person teams moved the unit from one location to another along the Hatteras’ periphery, setting a station approximately every 15 feet. At each station, they paused for 15 to 20 minutes to allow the sonar to make two 360-degree sweeps.

BlueView deployment — the first ever undertaken at a saltwater wreck site — presented some special challenges. One was short bottom time for the divers despite the relatively shallow depth. Hickerson, who coordinated the underwater activities of the Manta divers via radio, explains that the full face masks and wireless gear they used require far more air than needed in typical sport scuba. Most spent little more than a half-hour per dive in performance of their assigned tasks.

“We’d have one team working in the water, and the timing was such that we wanted overlap briefly to hand the equipment over,” she says. “We always had one team in the water, one ready to go and two teams doing their surface interval of 1½ to 2 hours.”

Positioning the tripod in the murky, choppy water posed problems of its own.

Flower Garden Banks Superintendent G.P. Schmahl explains: “We had a predetermined pattern that we wanted to place the instrument in because you want to get all sides of the part of the wreck that was out of the substrate. So you kind of had to kind of maneuver this instrument around each of the features.”

Compasses, however, failed because of the presence of iron in the shipwreck.

For orientation, the divers relied on a combination of sources: from touch to the fiberglass tape guide lines laid down earlier to verbal directions from the BlueView operator above — all the while contending with visibility as low as 5 to 7 feet, and often aggressive triggerfish.

Historian Ed Cotham takes a look at data being collected by the BlueView sonar system at the USS Hatteras site.

They had the benefit of a previous site map drawn by divers during the 2010 survey. Marine archaeologists Amanda Evans and Matt Keith, who directed surveys for BOEM from 2009-2011 and took part in drawing the map, lent their expertise to the 2012 expedition as well, engaging in setup activities while adding some final touches to their own work.

Topside, in the vessel’s dry laboratory, technician James Glaeser, an expert on collection and processing of BlueView data, monitored the stream of incoming digital information.

“The sonar looks all the way around itself twice,” he says. “The first time it’s pointed downward toward the sea floor, the second, up in more of a horizontal plane, so we’re getting two 360-degree scans from each floor location.”

After receiving the information from all 23 stations, Glaeser stitched together the scans to create a three-dimensional picture of everything above the seafloor at the site, and even a few inches below in some of the softer areas.

The final, dramatic image reveals the partly buried paddlewheel hubs as well as the main shaft connecting them, engine components (including what’s believed to be the steam chest) and an exposed portion of stern, complete with rudder post and armor.

Glaeser recalls the scramble to finish as the second night closed in. “We were a little rushed on field time,” he says. “But in the end it all came together. It was a good experience, and I think everybody is very happy with the results we got.”

Craig Howard of ExploreOcean, the Seattle-based educational foundation that sponsored the BlueView survey, plans to spread the excitement of oceanic discovery to young people nationwide through classroom materials.

“I didn’t grow up near the ocean, yet I fell in love with it early,” says Howard, who monitored cables and released sea turtles alongside high school students aboard the Manta. “I want kids to know that they can find a career in ocean studies using their particular talents, no matter what those may be.”

Delgado sees the successful mission as the first step toward bringing Texas’ rich maritime history to broad public awareness. In January 2013, Galveston’s Texas Seaport Museum mounted an exhibition commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Alabama vs. Hatteras battle. He plans on more to follow.

“The Texas Navy, when it existed, covered itself with glory at times and was key to keeping Texas independent for many years,” he says. “And parts of the Texas Navy became part of the U.S. Navy when Texas joined the Union. I think this is an important message to share in Texas.”

Related stories

La Salle Shipwreck: From a Watery Grave

3 Days in the Field: Galveston's Indomitable Spirit