Seeing Stars

State parks embrace measures to protect dark skies at night

By Rob McCorkle

“The stars at night are big and bright ...

Deep in the heart of Texas” — June Hershey and Don Swander

The 1942 Hit Parade song paying tribute to the Lone Star State’s starry skies strikes a sour note today in large cities nestled deep in the heart of Texas, where artificial light pollution has rendered all but the very brightest celestial bodies invisible to stargazers. But there’s a meteoric movement in Texas to hit the dimmer switch on manmade illumination that obscures night skies across much of our state.

Texas state parks remain among the few public places where the starry heavens can still be viewed in all their glory with minimal intrusion of artificial light. An ambitious dark skies initiative launched a couple of years ago has begun to bear stellar fruit.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department finds itself in the vanguard of the nascent dark skies movement that has its origins in Arizona, home of the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), which has been promoting night sky conservation and environmentally responsible outdoor lighting since 1988. The IDA (www.darksky.org) also serves as the clearinghouse for granting official certification to parks, communities and reserves through its Dark Sky Places Program.

Last summer, Copper Breaks State Park in the Panhandle and Enchanted Rock State Natural Area in the Hill Country became the first Texas state parks to be designated International Dark Sky Parks by IDA. Both sites received the highest Gold Tier night sky rating, joining Big Bend National Park (in 2012) and the City of Dripping Springs (in 2014) as the only Texas locations to have earned the coveted Dark Sky Places recognition. More Texas state parks are attempting to attain dark sky certification, which requires efforts to limit lighting and offer public education along with starry skies.

Enchanted Rock State Natural Area became one of the first Texas state parks to earn the designation of International Dark Sky Park.

In achieving dark sky status, Enchanted Rock and Copper Breaks join a select group. From the 2001 inception of the nonprofit organization’s Dark Sky Places conservation program through mid-2014, only eight communities, 19 parks and nine reserves (large swaths of remote lands) have achieved such status, according to program manager John Barentine in Tucson.

“Texas is rapidly becoming a national leader in the dark sky movement,” says Barentine. “There are some really dedicated folks in Texas’ parks and communities taking significant steps to protect night skies and educate policymakers and the public about the importance of preserving one of the state’s most precious natural resources.”

Chris Holmes, Texas state parks interpretive program leader, exudes a missionary zeal in rallying park staff behind an initiative he believes has cosmic implications for all Texans. He says more than a third of the 95 state parks have received lighting audits from IDA-trained volunteers, usually Texas master naturalists or astronomy club members.

“Lots of people, especially children, have never seen a truly dark sky or the Milky Way and marveled at the vastness of the universe and wondered about their place in it,” Holmes says. “The main culprit for this situation is the growing urban glow from countless light-polluting street, parking and commercial lights. State parks still offer Texans a dark preserve in which to experience the night skies as our ancestors enjoyed them thousands of years ago.”

Copper Breaks has been offering its popular StarWalk for 19 years, capitalizing on spectacular night sky viewing opportunities, to draw stargazers to the remote park 90 miles from Wichita Falls, the nearest metropolitan area. Like many Texas state parks that offer such events, Copper Breaks enlists knowledgeable “sky guide” volunteers — amateur astronomers — to lead participants in an exploration of the night sky with the naked eye and optical devices.

Superintendent David Turner replaced many outdoor lights with more efficient, low-light fixtures and retrofitted others with shields that point illumination toward the ground, helping keep charcoal night skies darker and utility bills lower. An added bonus: the park’s notable horned lizards, as well as other critters, are protected from artificial lighting that can have negative health and behavioral impacts on wildlife.

Similarly, Enchanted Rock State Natural Area has brought more than 90 percent of its lighting into compliance with IDA guidelines, says Superintendent Doug Cochran. Enchanted Rock started offering Star Parties in 2011 and also hosts monthly full moon hikes to educate the public about dark skies, light pollution and preservation.

“Not only do the steps taken save on energy costs, but they also guarantee that visitors from the city will enjoy a quality outdoor experience and a night sky uninterrupted by the glow of park lights,” Cochran says. “Children can come here and know that stars do exist.”

The state natural area boasts a donated Sky Quality Meter, installed at the visitors center, and a computer that records night sky darkness levels that can be viewed on the Enchanted Rock website. The next step, Cochran says, is to apply for a grant to convert all park lighting to LEDs (light-emitting diodes).

The Big Bend region has some of the state's darkest skies. Big Bend National Park retrofitted its lighting fixtures to make the park even darker. Big Bend Ranch State Park is the only Texas state park with a Bortle Scale rating of 1, indicating the darkest skies.

In spring of 2013, a $5,000 grant from a generous donor sparked a partnership between Texas state parks, the University of Texas McDonald Observatory and the Texas section of IDA to launch a pilot program in several Hill Country parks. Park rangers were provided with night sky training at the observatory to help develop star parties and received resource trunks with binoculars, star charts and other materials to facilitate their programs.

TPWD also launched a Lighting Assessment and Retrofit Project, contracting with several members of IDA’s Texas section to train a pool of volunteers to inventory existing lighting at state parks, recommend ways to improve lighting and coordinate with park managers to implement the changes.

Leading that charge has been Driftwood’s Cindy Luongo Cassidy, described by IDA’s Barentine as “nothing less than a force of nature” when it comes to promoting protection of Texas’ night skies. In consultation with fellow IDA member Steve Bosbach and McDonald Observatory’s Bill Wren, she wrote a volunteer training manual. To date, more than 20 state parks have received assessments, and another 20 parks have entered the process. The ultimate goal is to assess all of Texas’ 95 state parks, natural areas and historic sites.

More recently, Cassidy, who was hired several years ago by the City of Dripping Springs to monitor compliance with the municipal lighting ordinance, successfully applied to IDA to have the city designated a Dark Sky Community. In doing so, she had to overcome considerable opposition from local retailers and private landowners who balked at being told how they could (or could not) light their property.

“Instead of looking at it as a violation of their property rights, I suggested they needed to consider their neighbors’ rights not to have light intruding onto their property from next door,” Cassidy says. “It’s about being a good neighbor.”

She notes that artificial nighttime lighting has been documented to cause negative consequences for humans and animals. High levels of lighting can affect humans’ circadian rhythms and levels of serotonin, as well as animals’ hormone levels, mating and feeding habits — even a buck’s antler size. Safety for humans can be compromised, too, by blinding glare that can create dark places for intruders to hide.

Bill Wren of the McDonald Observatory in West Texas is a leader in Texas' dark skies movement. “I learned there is no conflict between having good lighting at night and dark skies,” Wren says.

Wren of the McDonald Observatory is considered the godfather of Texas’ dark skies movement. He has been spreading the dark skies gospel ever since attending an International Dark-Sky Association conference in 1990 during his first days as special assistant to the superintendent of the world-renowned observatory.

“I learned there is no conflict between having good lighting at night and dark skies,” Wren says. “We’re not anti-light. It’s real simple. If everyone would just keep their light on their own property, it would alleviate concerns about light pollution and light trespass.”

Wren says there have been some lighting ordinances around since 1978, but more cities, counties and even the State of Texas have jumped on the bandwagon in recent years.

For example, a 1999 state law mandates that state-funded projects, such as new highways and prisons, incorporate fully shielded or fully “cut-off” lighting that focuses light downward instead of shining outward and upward. In 2011, the Texas Legislature passed a law mandating that the seven West Texas and Big Bend counties surrounding the McDonald Observatory adopt outdoor lighting ordinances to protect what are the nation’s darkest night skies above any major observatory.

Despite such steps, Wren laments that sky glow from drilling rigs, gas flaring and field oil storage facilities in the Permian Basin is affecting the view from atop Mount Locke, where some of the world’s most powerful telescopes are trained on the farthest reaches of pristine dark skies.

“They’ve been lighting up the horizon with drilling rigs and gas flares in the past three or four years,” Wren says. “It’s good for the economy, but the impact on night skies is unmistakable.”

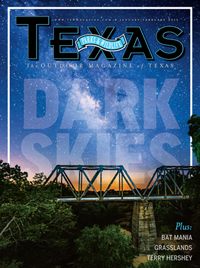

Copper Breaks State Park, below, has been offering its popular StarWalk for 19 years. The park became an International Dark Sky Park last summer.

A joint McDonald Observatory and Pioneer Energy Services report resulting from a study of lighting at a typical oil rig concluded that the careful and innovative use of lighting, especially LEDs, can increase cost efficiency, provide environmental protection and improve safety by reducing blinding glare. Wren hopes other oil companies will follow Pioneer’s lead. He’s been contacted by Chevron about ways to upgrade its lighting and prevent glare to improve workers’ health and safety and save on utility costs.

Wren has worked with a number of cities, including nearby Alpine, to create lighting ordinances and finds himself in demand as an expert on the topic. He praises the TPWD leadership for embracing the dark skies gestalt.

“‘The stars at night are big and bright.’ Why is that a catchy tune? It appeals to something beyond the mundane and is humbling; we’re real small, but there’s a sense of being connected to something really big,” Wren says.

He wonders about the unforeseen long-term consequences of polluting our night skies with manmade light.

“By raising generation after generation of people who have never seen a naturally dark sky before,” he says, “we’re toying with the forces of nature. There’s something intangible, but significant, in viewing starry skies. It’s the heart of who we are.”

Stargazing in State ParksInterested in learning more about upcoming stargazing events taking place near you? Visit www.tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/parks/things-to-do/stargazing-in-state-parks. The website also ranks the darkness of skies above Texas state parks on the Bortle Scale — from the darkest, such as Big Bend Ranch State Park (Class 1), to the not-so-dark sites (Classes 4-9). In addition to Big Bend Ranch, 13 other state parks are rated as having “very dark skies.” Class 2 parks: Balmorhea, Barton Warnock Visitor Center, Caprock Canyons, Copper Breaks, Davis Mountains, Devil’s Sinkhole, Devils River, Kickapoo Cavern and Seminole Canyon. Class 3 parks: Colorado Bend, Enchanted Rock, Lost Maples and South Llano River. |

» Like this story? If you enjoy reading articles like this, subscribe to Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine.