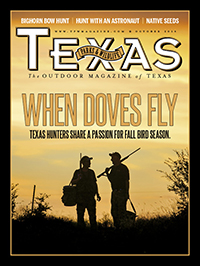

Bighorn by Bow

Round Rock's mayor scores the first ram by bow and arrow on Texas public land.

By John Jefferson

Elephant Mountain was iced over, with fog so dense that visibility was measured in feet. As the hunters drove closer to the top of the mountain, the atmosphere cleared. Scanning for bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) was still challenging but improving with elevation.

The four hunters reached the summit when the spotter reported that he had seen 12 sheep at lower elevation. Two were “shooters” — big enough to harvest.

While going down sounds easier than climbing up, sometimes that’s not the case. The way down involved trekking through a nearly impassible gorge littered with boulders and thorny plants. Despite the daunting landscape, the hunters decided to make a stalk from the top.

Round Rock Mayor Alan McGraw, an experienced hunter and outdoorsman, was making his first bighorn ram hunt, accompanied by his wife, Kathy, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department wildlife biologist Dewey Stockbridge as guide. Cody McEntire, a wildlife technician on TPWD’s Elephant Mountain Wildlife Management Area, came along, and Froylan Hernandez, TPWD’s bighorn sheep program leader, served as a spotter from the top of Elephant Mountain. The peak is south of Alpine in West Texas.

That unforgiving terrain tested their endurance and their apparel. The soles of Kathy’s boots started separating from the abuse and had to be duct-taped together. She kept going. No country for old boots or new ones not adequately broken-in.

The group struggled inch by inch to within 60 yards of the rams. Success seemed in sight. The first day of the 10-day hunt looked as if it was about to be the last. The reward was a “gimme putt” away.

But one nervous young ram seemed aware of them. There were two shooters in the herd, as Hernandez had said. One had flared horns — ones that spread out to the sides. The other had boxy horns, meaning its horns stayed closer to the head in a tight curl. Both were trophy rams.

Fog hangs in a valley at Elephant Mountain Wildlife Management Area.

McGraw had told the WMA personnel that he didn’t care about taking the biggest ram on the mountain. The thrill of the hunt mattered far more than the size of the prize.

The flared-horn ram got up and moved out farther. It was getting on into evening; McGraw was concerned about having to try to trail a wounded ram in fading light, especially over rocky hills and draws. He passed on that shot.

He and Stockbridge worked their way closer, but the rams were lying down, making it hard to see them. The two that qualified as shooters headed downhill, too far for a shot, and finally busted, distancing themselves from the hunting party. You see, McGraw was not carrying a high-powered, flat-shooting rifle with a strong, light-gathering telescopic sight — he was hunting with a bow and arrow.

His judgment had avoided risking a wounding shot. While the first stalk ended disappointingly there in the twilight calm, getting back to camp would be a final bit of adventure for the day.

Their choices: Climb back up Elephant Mountain in the ensuing darkness to the truck, head straight down the mountain or strike out cross-country to the lodge. They decided going back up the mountain was not an option — way too difficult. Going down the mountain would be precarious and still leave the party a long way from home. Going across the mountain won by consensus.

The four walked out, leaving the truck for later. The walk was long — more than two miles — and treacherous. It was after dark when they reached the lodge.

“Thank goodness we had moonlight,” McGraw said later. “And thank goodness we didn’t break an ankle. In the end, we were exhausted.”

They might have wondered if the going up was worth the coming down. The risk of tripping, slipping or stumbling and falling increases exponentially going downhill in the dark. At least in February the hunting party was not as concerned about rattlesnakes as they might have been in June. Warm weather adds different stresses.

After that long march in the mountainous high desert, they probably slept well that night, with visions of torn boots and bighorns dancing in their heads. After all, this was only Day One.

Many people don’t know there are bighorns in Texas, nor that they can be hunted. Permits are required, and hen’s teeth are easier to obtain. About 15 permits are awarded each year, depending on that year’s census. One permit goes to the winner of TPWD’s Grand Slam drawing, and another goes to the public hunt program’s bighorn sheep hunt drawing winner. One other permit is usually given on a rotating basis to a worthy conservation organization each year to be auctioned. McGraw’s permit was a Texas Wildlife Association auction permit.

Proceeds from auctions are divided between the organization and TPWD. For more information on the two TPWD drawings, visit www.tpwd.texas.gov/drawnhunts.

Bighorns in Texas reside in the mountains of the Trans-Pecos region, ranging through several private ranches that partner with TPWD in stewarding the sheep, and three TPWD wildlife management areas: Elephant Mountain, Black Gap and Sierra Diablo. Big Bend Ranch State Park and Big Bend National Park also have some. Altogether, roughly 1,500 bighorns exist in Texas.

Bighorn rams prefer rough, rocky habitats.

State management is greatly aided by the Texas Bighorn Society (TBS), a private nonprofit group dedicated to restoring bighorn sheep. TBS provides voluntary manpower, materials and money to create habitat-improving elements, benefiting not only sheep but all forms of wildlife.

Once abundant, bighorns historically suffered from disease, poaching and fences that restricted movement to food and water. Bighorns had virtually disappeared from Texas by 1958.

Restocking efforts through the years created a yo-yo effect. As the population increased after importing sheep from Arizona, Baja, Utah and Nevada, disease and mountain lion predation brought them down again. The 1983 construction of a brood facility at Sierra Diablo (by TBS) and the private donation of Elephant Mountain to TPWD were the turning points. The sheep population stabilized and continued to expand. More money came into the program through those auctions as well as excise tax proceeds, hunting license fees and the sale of Texas Grand Slam tickets. Today we see what may be the high-water mark for bighorn conservation, though the water looks to still be rising.

Alan McGraw’s hunt was a 10-day hunt package. He could take it in two five-day segments, if needed. The second day of his hunt was a reprise of the first day’s weather — cold and foggy, with most of the rams hanging out in the next ZIP code, apparently. The hunters did a lot of driving and stalking. Once, young rams came between them and two rams they were working. Their last stalk of the day began at a measured 637 yards — that’s six football fields plus nearly four more first downs. Peeping and hiding behind rocks and ridges, the group thought they had slipped close enough for a shot.

The hunters topped a ridge, but the rams were still 250 yards away, and there was no way to get closer. They backed out and headed for the lodge. Maybe tomorrow.

Sadly, the third day of the hunt turned out no better. More fog. More driving, trying to peer through the soup. They came up on four young rams that they had seen several times. Stockbridge said one was mature and would measure about 160 inches of horn. He wanted to keep it in mind as a backup if nothing better materialized.

McGraw, who started the hunt saying he wasn’t very particular about size, was becoming even less so.

It practically takes Comanche stalking skills to get within bow range — 40 to 50 yards for average archers. McGraw consistently practiced at 90 yards.

“That makes 40 yards seem easy,” he explains. But bighorns are hard to hunt.

TPWD had carefully considered McGraw’s request to bow-hunt a ram.

Alan McGraw, left, and Cody McEntire scan the landscape for bighorns.

“Ultimately,” Executive Director Carter Smith said, “we were persuaded by the fact that Alan has hunted big game on multiple continents in a wide variety of habitats and circumstances.”

They stalked a nice ram, but again couldn’t get close enough. Hernandez directed them to another good ram, and they went after it, only to see it spooked just as they got within range. Another day, another disappointment. They headed to the lodge.

“After three days, I was getting real concerned whether we could do it with a bow,” McGraw admitted. Back at the lodge, they began talking about possible dates for the second five days.

Day Four dawned clear. No fog. But windy. This time, McGraw spotted a nice ram. They had to drive to the top and stalk down over the ridge. The four people moved stealthily, taking advantage of rocks and brush. Stockbridge stopped abruptly; the rams were feeding right in front of them, 54 yards away!

McGraw couldn’t get a shot, so he belly-crawled closer. When he raised up, the ram was below him and behind a rock. No clear shot, so he back-crawled ever so carefully. The ram looked toward them, then away. Then the ram looked back toward them. McGraw waited.

Both rams looked toward the bottom of the mountain. McGraw rose to his knees, thankful to be wearing knee pads, and drew his bow. He could see the torso of the ram but not the legs. He had to get just high enough to shoot over the rock and avoid brush. His bow caught in the grass and he moved slightly to break it free.

His movement blended with the grass blowing in the wind, raising no alarm. He put the 50-yard sighting pin on the mark, took a breath … and released.

The ram bolted and ran, showing no sign of being hit. Stockbridge said the arrow started well enough, but the wind took it to the right. They jumped up to follow it. McGraw pulled out another arrow, hoping the ram would stop. They topped the ridge but saw to their dismay that the rams were nowhere in sight.

“My biggest fear,” McGraw said, “was not a missed shot, but a bad shot. It was gut-wrenching.”

McEntire contacted the spotters below.

“Its legs are no longer kicking,” came the word from the spotters.

“What!” McGraw exclaimed. “You mean I hit it?”

McGraw looked down, perhaps to wipe his eyes, and noticed they were standing in a trail of blood. The bighorn hadn’t gone 60 yards.

Alan McGraw's patience was rewarded with a trophy bighorn.

The ram scored 172-7/8, enough to make the Boone and Crockett and the Pope and Young record books. It is also the first bighorn taken on public land in Texas with a bow and the first Pope and Young ram from Texas, quite a historic accomplishment.

McGraw credits his success to Stockbridge’s knowledge of the sheep and the mountain. He recovered his arrow, and will use it on his next sheep hunt, in Canada.

» Like this story? If you enjoy reading articles like this, subscribe to Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine.

Related stories

Big Time Texas Hunts Lottery Offers Chance for Hunting Opportunities