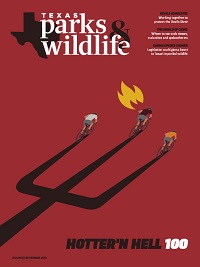

Devils Advocates

Landowners and conservation groups work to preserve the pristine Devils River.

By Tom Harvey

At first sight, most anyone can see the Devils River is special. The Caribbean aquamarine color of its crystal-clear water is stunning, winding through arid, rocky canyons.

This is rough country, covered in thorns, jagged rocks and steep cliffs, hence the name “Devils.” But down by the river, it’s heavenly. Prized by anglers for feisty game fish, the river is also home to rare species like the Devils River minnow and the Texas hornshell, a freshwater mussel that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed as endangered in March.

There’s more here than beauty. In drought-prone Texas, water is life, for people, fish and wildlife, livestock and agriculture; the spring-rich Devils sends benefits way beyond its banks. Somewhere between 15-18 percent of water in the Rio Grande below Lake Amistad comes from the Devils River.

“The Devils is the least disturbed, least developed river in Texas,” says Chad Norris, a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department aquatic biologist who has made a career of studying springs and their connections with rivers. “By extension it has high water quality and an exceptionally diverse biotic community, which includes endangered species. In terms of how we manage watersheds, the Devils offers an opportunity that many parts of Texas only wish they could achieve.”

The river is special, but it’s also at risk. Today the river’s remote beauty, wide-open spaces, clear water and dark skies face a variety of threats.

Preserving wildness

For most of the past century, ranching has been the main land use along the river, and that’s helped protect the river and keep the region’s wild character intact.

Multigenerational ranching families with deep roots in the rocky soil are still prominent conservation advocates. That includes ranchers like Alice Ball Strunk, whose family still owns the river’s headwater springs on Hudspeth River Ranch. Their first ranch property was purchased in 1905 by Alice’s great-grandfather Claude B. Hudspeth, known as the “cowboy congressman,” first a state representative and senator and then serving in the U.S. Congress, 1919-1931.

Because of its beauty and importance, huge public and private investments have gone into safeguarding the Devils River. The state acquired the original 20,000-acre Del Norte Unit of Devils River State Natural Area in 1988, and acquired the newer 18,000-acre Dan A. Hughes Unit in 2011 using $10 million in private donations. In addition to that, there’s the 57,000-acre Amistad National Recreation Area into which the river flows. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, the Devils River Conservancy and others have collaborated for years to set research priorities and develop sound science, fund projects to study and conserve the river, host field days and hold educational workshops.

Yet there is still more. The Devils River watershed represents the nonprofit Nature Conservancy’s single largest conservation investment in Texas.

“In 1991, the Dolan Falls property came up for sale and the Nature Conservancy bought it, realizing how special it was,” says Laura Huffman, Nature Conservancy of Texas state director. “Since then, we’ve worked with conservation-minded landowners to safeguard more than 100,000 additional acres along the river through conservation easements — voluntary land-use agreements with private landowners that permanently conserve land and water.”

The easements restrict the properties from being subdivided into smaller parcels, prohibit water from being exported off the property and limit development close to the river and in other ecologically sensitive areas, like Fern Cave, one of the state’s largest Mexican free-tailed bat maternity colonies. The Texas Agricultural Land Trust also holds conservation easements along the Devils, including one on Sycamore Canyon Ranch owned by the Russell family, who won a Lone Star Land Steward Award in 2014.

“Partnering with private landowners on the Devils is vital — they’re some of the most important stewards of Texas’ natural resources,” Huffman says.

Paddlers hit the water

For decades, adventurers have been drawn to kayak and canoe the Devils River — it has become perhaps a misguided ambition of many Texas paddlers to “conquer” the Devils, making the arduous trip around boulders and over shallow spots from Baker’s Crossing down to Lake Amistad. Some adventurers have come ill-prepared. That’s not only dangerous, but it’s raised mounting concerns among riverside landowners about trespassing and degradation of the watershed from increasing human impact.

Fortunately, progress has been made to preserve the unique wilderness recreation experience and protect it for future generations. TPWD and the Devils River Conservancy work to educate visitors and manage paddler numbers through a permit system.

Groundwater pumping

However, there is a bigger water challenge. Business conglomerates have shopped plans to do things like pump groundwater in Val Verde County and build a pipeline to ship it north toward San Angelo — as one proposal said, “marketing this water for sale for use in hydrocarbon exploration and by municipalities.”

That project has yet to materialize, but it raised concerns that someone could pump large amounts of groundwater, and that might dry up the springs that feed the river.

Such concerns are not guesswork. In 2017, Ron Green, a hydrologist with the nonprofit Southwest Research Institute, completed a study of water resource management of the Devils River watershed.

“What our study did was to show the sensitive linkage between groundwater pumping and surface water flow,” Green says. “We developed a model showing what happens when you remove groundwater by pumping.”

What happens? There is less water in the river.

“Ron Green’s work shows that whether you’re pumping groundwater around Lake Amistad or farther up the river,” says Norris, “if you’re in a high-producing area, for every acre-foot of groundwater pumped that’s an acre-foot less of water in the river.”

In Texas, where 95 percent of the landscape is privately owned, property rights are paramount. Groundwater use goes by the “rule of capture,” a legal principle that has been interpreted to mean that someone can pump all the water they want even if that causes neighboring wells to go dry. There is a recourse: Groundwater conservation districts governed by locally elected boards have the power to regulate pumping in various ways. They can limit the withdrawal rate, the spacing of wells and the total volume pumped annually. However, if groundwater is available, they cannot decide who gets to pump and who doesn’t.

Val Verde County has yet to form a groundwater district, despite years of talk. It came close two legislative sessions ago, with a bill to create a district filed by Rep. Poncho Nevárez, whose legislative district includes Del Rio and much of West Texas.

“We’re starting to enter another drought in our state, and this round may be fiercer,” Nevárez notes. “The Devils is the most pristine or cleanest river in Texas; there’s not another one like it, and we want to make sure that continues. It boils down to a couple of things: how much water is there, and will pumping it affect the viability of the river. Past that, you add to the mix, if I pump here along the river, what does that mean over there? In the coming session, I would file another bill as a placeholder. But I won’t advance a bill unless I have everyone signing on.”

Getting unanimous agreement may not be easy. But mounting evidence, including Green’s study, indicates that more landowners may be coming around to the idea of a groundwater district.

Dell Dickinson and his brothers own the 7,000-acre Skyline Ranch in Val Verde County, with about 4.5 miles of riverfront on the west side of the river. He also manages the Tocor River Ranch, about 2,000 acres with about 2 miles of river frontage. Dickinson’s family first came to the Devils in the late 1800s, when his great-grandfather Tom Wilson bought land near the small community of Juno. His mom’s father bought the Skyline Ranch in 1942.

Devils River rancher Dell Dickinson can see the lights of distant wind farms from his deck.

“I’m for having a groundwater management district,” Dickinson says. “I would like to see order. Water is becoming the gold standard. We’re all going to have to learn to share, whether we like it or not. Without some type of management vehicle, the chances are too great that some individuals, perhaps thinking of profit only, would ruin things for everybody else.”

Speaking with Dickinson, you get the impression his attitudes have evolved over time. Like other multigenerational ranch families along the upper Devils, he is a staunch proponent of property rights.

“I am a very strong private property rights advocate,” Dickinson says. “However, my personal definition of that is that I can do anything with and on my land as long as it’s legal, ethical and doesn’t harm my neighbor.”

While there has not been total agreement on groundwater, a new issue appears to be uniting many voices in the region, joining against what they perceive as a common threat to all.

Windmills on the horizon

In 2017, French wind power company Akuo Energy built a 69-turbine wind project in Val Verde County, the Rocksprings Val Verde Wind Farm. This is about 6 miles east of the southern unit of TPWD’s Devils River State Natural Area. One of the major leases in the wind farm is Brazos Highland Properties LP, a Chinese-based investment firm.

In addition to its part of the Rocksprings wind farm, Brazos Highland owns tens of thousands of additional acres on both sides of the Devils River, and on the Pecos River.

Locals believe Brazos Highland intends to further develop wind energy on these acres, raising the prospect of dozens or hundreds more wind turbines on the horizon. It’s a tricky balance since wind power clearly has both environmental benefits and some drawbacks. The issue is where the turbines are built and what might be affected nearby.

“The first night I walked out on the deck at the headquarters house after the Rocksprings wind farm navigation lights were activated, I was appalled,” Dickinson says. “One of the things we love about this country is stargazing. The number of stars visible in these dark skies is stunning. If you can imagine 69 red navigation lights all blinking together in synchronous timing, it looks like the extraterrestrials have landed. Long story short, I no longer visit the deck at night because of this visual and light pollution being foisted on me by a foreign entity, who apparently has no regard for his neighbors.”

Dickinson is not alone. Dozens of people, organizations and businesses, led by the Devils River Conservancy, have organized in opposition. And, in a move that surprised some observers, the Val Verde County Commissioners Court passed a resolution this spring opposing wind farm expansion.

“You have to visualize this,” Dickinson says. “As the crow flies, the turbines are 18 miles from our ranch house. At 18 miles away, those things are so huge — more than 450 feet tall — that I can count each one individually with my naked eye, and I can see the individual blades rotating.”

Opponents say it’s about more than dark skies and vistas. They cite safety concerns about the proximity to Laughlin Air Force Base in Del Rio, issues for safely monitoring border security, potential impacts to endangered species, property rights and land values. They say wind turbine construction and operation here undermine decades of public and private conservation investments along the river, and point out that wind farms are high on the scale in terms of land-use intensity.

“Given that the public currently views wind power as a viable alternative energy source, it only makes sense to locate them to ‘disturbed’ areas which are already altered to such an extent that they have limited value to support natural communities,” Dickinson says. “Studies show that the contiguous United States has more than enough net ‘disturbed’ areas to site wind farms, thus saving ‘non-disturbed’ areas like the Devils River watershed. Bottom line, destroying one environment in the name of trying to protect another makes no sense at all.”

What happens on the Devils River could set important precedents for other rivers across Texas. Slowly growing consensus built over decades appears to be centering on conservation for the common good. The Devils River Conservancy, relatively new on the scene, is making creative strides to educate paddlers, landowners and others, providing science-based decision-making tools to the community, and working to change the visitor mindset from “conquer the Devils” to “be a Devils advocate.”