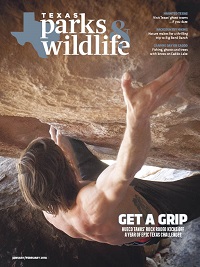

Rock That Climb

Each year, Hueco Rock Rodeo crowns the world’s greatest boulderer.

by Russell Roe

The bouldering route known as Esperanza stood for years as the hardest climb at Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site, a place known for pushing the limits of what’s physically possible to climb.

Small cracks, edges and protrusions line the ceiling of a cave, requiring climbers to move precisely and powerfully across this near-horizontal surface to a hueco, or large hole, that serves as the finishing hold. In years past, when any climber actually completed this test-piece route, which may have also been the hardest climb in the U.S., it often made news in the climbing blogs and magazines.

Daniel Woods is lying on his back on the floor of the Esperanza cave, looking up at the holds he needs to grip and visualizing the moves in his mind. He moves his hands through the air as if he's choreographing a dance.

He’s already practiced a couple of the hardest moves and just needs to put the whole sequence together. Finishing Esperanza could send a clear message to the rest of the climbers competing in the Hueco Rock Rodeo that he’s the climber to beat.

Woods chalks up his hands, attaches himself to the rock and crimps and grips his way across the ceiling, moving like the large spider tattooed on his torso. He sets himself up for the finish — a dynamic move to the hueco — and launches.

Instead of hanging off the hueco in triumph, he finds himself back on the floor of the cave, having missed the hueco by just inches.

“I just felt my left hand go phphphphttt,” he says.

His rivals take note. Maybe Woods can be beat.

Each year, climbers gather at this desert outpost on the outskirts of El Paso for the Hueco Rock Rodeo, the premier outdoor bouldering competition in America. The Rodeo celebrated its 24th occurrence with 214 competitors in February 2017. The competition attracts climbers from around the country — and even a few foreign countries — who want to see how they fare on the park’s rarefied rock.

Hueco Tanks occupies a special place in American climbing. The history of bouldering in North America is written in its rocks. Bouldering really took off as its own discipline in the 1990s as climbers recognized that attempting shorter ascents without ropes could be an end in itself and not just serve as practice for longer climbs. It turns out that Hueco Tanks was the perfect place to do it — a place with too many boulders to count, an unusual, high-quality rock type with a sandpaper-like texture, plus countless cracks, dimples and the namesake huecos that provide perfect holds for climbing.

El Paso's mild winter weather gave climbers a place to go when the mountains of Colorado and elsewhere were covered in snow. Climbers started coming from around the world and made the park the first climbing destination focused mainly on bouldering.

“Hueco Tanks was the birthplace of modern bouldering,” says Albert Alvarez, organizer of the Rock Rodeo. “If people wanted to test their abilities, they came here.”

Hueco climbs with memorable names such as Nobody Here Gets Out Alive, Moonshine Roof and Full Service stand as all-time American bouldering classics.

A whole bouldering culture developed over the years, with its own adherents, difficulty rating system, gear and lingo. The Rock Rodeo celebrates that and Hueco’s role in creating it.

“That was sick, dude,” a climber says to Ben Hanna, who just completed the difficult roof problem Left Martini, which shares the same cave system as Esperanza.

Hanna had fallen off the route a few minutes earlier. Some of the competition’s other top climbers had tried it and failed as well. Hanna then executes a complex orchestration of hands and feet across the ceiling of the cave, sticking to the roof like a piece of gum on the underside of a table.

Woods can only watch in wonder and shake his head. “He’s in first,” he says after Hanna’s climb.

In contrast to Woods, whose intensity and sculpted physique could belong to an Olympic gymnast, Hanna’s gangly body makes him look more like somebody’s skinny kid brother than a hard-core climber.

Still, the physicality required to climb at bouldering’s top levels is undeniable. Bouldering condenses the complete climbing experience into 15 to 20 feet of rock, intensifying the gymnastic qualities of the sport and adding the “scare factor” of hitting the ground if you fall. It requires a potent combination of strength, balance, power, stamina, body control, technique and courage. Executing a move at the limits of your physical and mental boundaries while 20 feet off the ground isn’t for everyone.

Bouldering’s difficulty rating system, the V Scale, was developed at Hueco Tanks to measure the intensity of the climbs. The lowest rating, V0, already sets a high bar, corresponding to what would be an intermediate to advanced climb on the regular climbing scale. Climbs with higher ratings, such as Esperanza’s V14, are achievable by only a handful of people in the world.

One competitor, Nathaniel Coleman, is fresh off a victory at the Bouldering Open National Championship, making him the country’s top indoor boulderer at this moment. The Rock Rodeo marks the first time he’s been at Hueco Tanks.

“I’m looking forward to getting on a bunch of hard climbs and enjoying the day,” he says. Nursing a slight finger injury, he wants to “stay off any heinous crimper problems.” Translation: no super-hard climbs that feature extra-small holds.

How will the nation’s top indoor boulderer fare at Hueco’s testing grounds? His first climbs aren’t promising. Coleman struggles through several attempts of Dean’s Journey (V10), and Left Martini (V10) just isn’t happening for him either.

Both Coleman and Woods are realizing they are going to have to downgrade their aspirations for the day.

They decide to move on to the top of North Mountain, where they attempt Barefoot on Sacred Ground (V12), a “highball” boulder problem, meaning the finish is high enough to risk serious injury. The climbers spread out foam pads to cushion any falls.

These “crash pads,” a Hueco innovation, are essential pieces of gear for most boulderers.

Keenan Takahashi, a climber from California, is already working on Barefoot and makes it to the top. Hanna takes a turn and pops off after a few moves; Coleman has trouble getting started. Woods falls but feels hopeful.

Coleman gives up and moves on to the easier See Spot Run (V6). “I made it up a boulder!” he says at the top, poking fun at his struggles.

Climbers often spend multiple attempts working out the moves on a climb. Each bouldering route, or “boulder problem,” follows a distinct line up the rock, with a defined start and finish. Handholds and footholds — edges, cracks, pockets and the park’s signature huecos — are often marked with the gymnastic chalk that climbers use to keep their hands dry. For the Rodeo, organizers select nearly 200 of the park's several hundred routes for the climbers to choose from.

The challenge comes in finding the right sequence of hand moves, foot moves and body positions to make it from bottom to top without falling. Sometimes, gripping a hold a certain way makes a difference; other times, putting more weight on one foot or the other can enable upward progress. It’s like solving a puzzle. The other part of the challenge is solving the puzzle before your fingers or forearms flame out.

The climbers compete against one another, but they also support their fellow climbers, shouting encouragement — “You got it!” — and pushing them to do their best.

They’re even willing to share their particular sequence in finishing a climb. Here are Woods’ instructions to a fellow climber on a route called Loaded With Power (V10), untranslated from the original climber-speak: “Start on the loaf and go up to the pinch.

Then knee-bar, crimp, crimp and ride it all the way to the top.” Got it?

Hanna and Woods eat periodically through the day to maintain their strength. Hanna tears open a Pop-Tart package; Woods pulls out a Ziploc bag of scrambled eggs and bacon scored from the hotel breakfast buffet. The discussion among one group turns to what fruits could be eaten in their entirety — skin and all. Oranges? Yes. Kiwi? Definitely. Bananas? Not so sure about that one.

On the women’s side, competitors are cranking out climbs such as Fern Roof (V8) and Stegosaurus (V7). Juliet Hammer of Colorado is attempting a climb that requires a heel hook, which means she puts her foot over her head and secures her heel on a ledge above in order to pull up and over a bulge.

Kyra Condie, competing in her first Rodeo, decides to tackle Free Willy (V10). She falls at the top.

“That sun was right in my face,” she says. “And there was pain. There was definitely pain.”

As the competitors go from climb to climb, they sometimes pass Native American pictographs that adorn rock walls and overhangs. Hueco Tanks harbors a world-class collection of rock art, providing a visual link to the park’s rich history.

“There’s something more going on in the park than just climbing,” says Ander Rockstad, who has traveled to Hueco Tanks to climb every winter for more than a decade. “This place is powerful. It demands respect. There’s a long line of people who have found this place special, and climbers are just the latest pilgrims.”

TPWD is constantly attempting to balance the sacredness of the site and the desire for recreation. As its name spells out, Hueco Tanks is both a state park and a state historic site.

In 1998, the park began limiting access to much of the park and capping the number of visitors, worried about the effects of increased erosion, devegetation and vandalism. Climbers and other visitors can explore the North Mountain area of the park on their own (if they secure one of the daily permits) but must be accompanied by a guide in the other areas of the park.

This past year, climbers worked with a park survey team using digital technology to identify previously unknown pictographs. The survey found rock paintings at 30 new sites, which were then closed to recreational activity.

The Rock Rodeo, which was first staged in 1989 by the El Paso Climbers Club, was put on hold for several years after the 1998 restrictions took effect. In 2003, Rob Rice of the Hueco Rock Ranch revived the competition, and the American Alpine Club now runs the ranch and the contest.

The early days of the Rodeo were freewheeling affairs attracting local and regional climbers who wanted to climb hard, hang out with other climbers and — just as important — celebrate afterward at Pete’s, a ramshackle Quonset hut that served as the unofficial headquarters for the Hueco climbing scene. There was little or no prize money, and prizes included such items as velvet Elvis paintings and bottles of tequila.

Today’s Rodeo attracts some of the world’s best climbers and offers more lucrative prizes, but it still channels the same spirit of competition and camaraderie.

“It’s a competition, but it’s also like a giant jam session with your friends,” Woods says.

In the late afternoon, climbers head to the Hueco Rock Ranch for the nighttime activities, including food trucks, vendor booths, a raffle, a bonfire, a DJ and an awards ceremony. The less competitive recreational climbers who participated the day before stick around to enjoy the festivities and compare notes on the competition.

Climbers have until 5 p.m. to turn in their scorecards. The ascents are given point values based on their difficulty, and climbers use their top six results to come up with a final point total.

In the end, it is Woods who rules the day. The now-six-time champion from Colorado seals his victory with an impressive late-afternoon ascent of Diabolique (V13) in a tucked-away North Mountain alcove. Takahashi places second, with Hanna third.

On the women’s side, Condie takes the victory, followed by Molly Rennie and Hammer.

The next morning, a fierce wind blows across the desert, ushering out the competitors as they pack up and head home. Many will be back this year — pilgrims returning to bouldering’s spiritual home for another epic challenge.

Sacred Site In addition to being an international climbing destination, Hueco Tanks is home to a world-renowned body of pictographs. Over the past several thousand years, prehistoric people and Native Americans left their indelible marks — images of masks, snakes, water symbols and other figures — on the rock faces. The collection of ancient images at Hueco continues to be profoundly important to a number of Native American tribes. TPWD recognizes the significance of the pictographs and is pursuing a National Historic Landmark nomination. The park's public use plan, amended in 2016 with help from Native American groups, climbers and other stakeholders, reaffirms TPWD's dual goals of preserving these cultural resources and allowing access to climbing. TPWD continues to find rock art in the park. In the past year, more than 30 new sites were discovered as a result of concerted efforts to find undiscovered pictographs. TPWD has spent many hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars working with conservators to remove graffiti from the park while not harming the pictographs. In a groundbreaking technique for rock art conservation, TPWD and a team of professionals from across the country have used lasers that burn off the modern paints but do not harm the ancient pigments. TPWD staff and volunteers lead tours to rock art sites on a regular basis. Park visitors must be accompanied by a guide in most of the park to ensure protection of the fragile desert resources and rock art, and all visitors must watch an orientation video. |

Related stories