LUNA

(Actias luna)

Photo © Steven Russell Smith Photos

Caterpillars can be pesky, but their transformations into moths are worth the trouble.

By Sheryl Smith-Rodgers

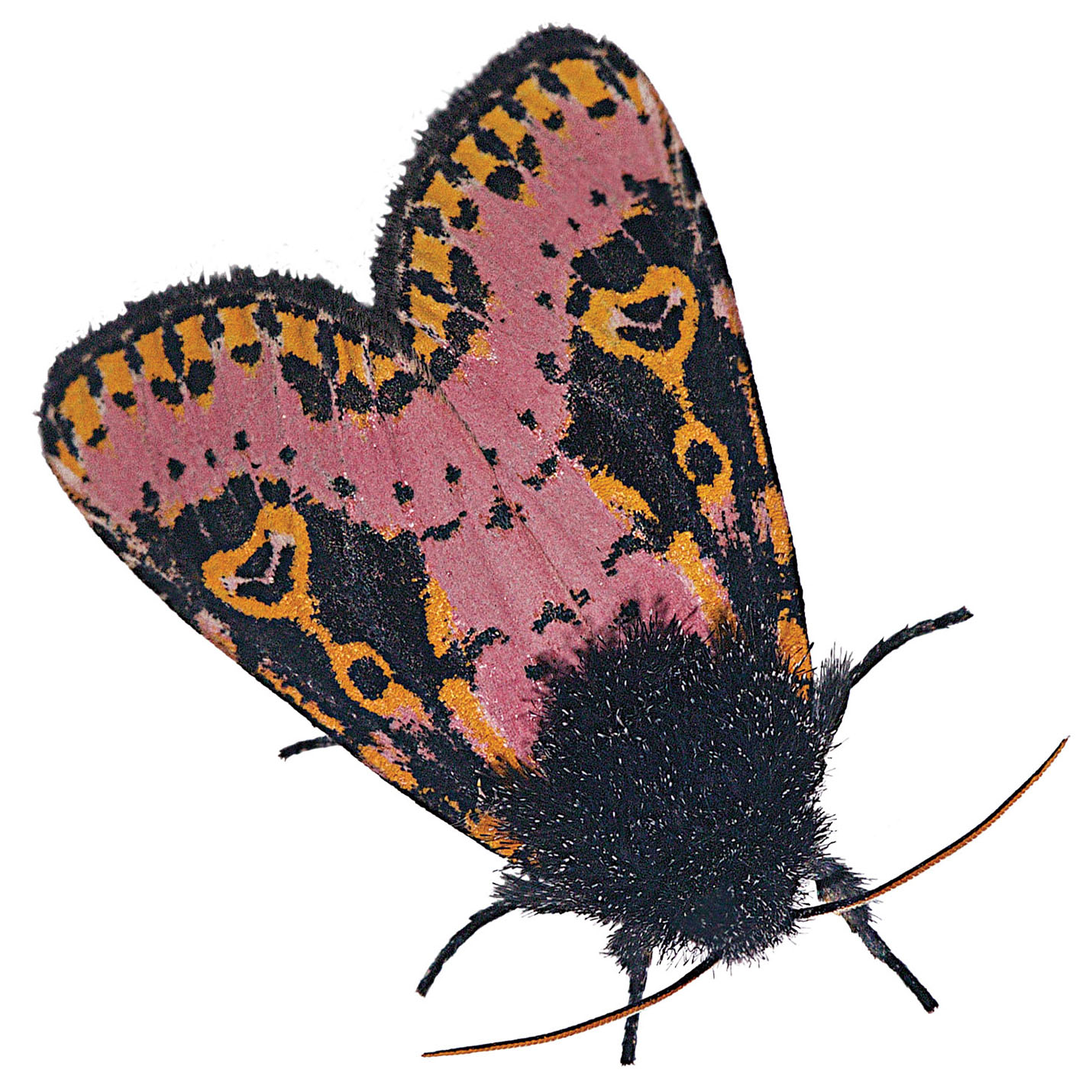

Photo © Melinda Fawver/Dreamstime.com

IMPERIAL

(Eacles imperialis)

Outfitted in black wetsuits, the two scientists — working beneath bald cypresses draped with Spanish moss — lift rocks from the creek’s bottom and eyeball each one’s underside with magnifiers. On the rocky bank, landowner Delmar Cain stands ready with a plastic bag of assorted specimen containers. His cue to open one comes when Jason Hall, cupping a wet rock in one hand, wades over to his wife, Alma Solis.

“I’ve definitely found a live one this time,” Hall announces, using needle-nose tweezers to fold back a slimy sheet of algae on the rock. Under the silken blanket nestles a worm-like animal, light olive in color and no longer than a pencil eraser. Gently, he prods the body. “See the brown head?”

Cain peers at the insect, then holds out a small glass vial. Carefully, Hall drops in his find — an aquatic moth larva. It would be among dozens of caterpillars, pupae in cocoons and winged adults collected during the couple’s four-day visit to Spring Creek on Cain’s rural property in Kendall County. All would help further Solis’ studies on aquatic moth species.

But, hold on — aquatic caterpillars? Yes, as strange as that sounds. Like dragonflies, mayflies and mosquitoes, a few moths begin life in streams, ponds and marshes. They may (or may not) have gills and feed on algae or aquatic plants until they cocoon and emerge as winged adults. By far, though, the majority of moth caterpillars are terrestrial.

Moth caterpillars are also despised, especially by gardeners. Think about fat hornworms on tomato plants. Common reactions to their presence typically end with a messy splat!

Now, consider this scenario: The caterpillars happily live on and morph into large-bodied sphinx moths that hover like hummingbirds as they nectar on flowers. Even stinging asps, fall armyworms and woolly bear caterpillars can pupate into beautifully marked moths worthy of admiration.

Photo © Sheryl Smith-Rodgers

Landowner Delmar Cain assists Smithsonian research entomologists Alma Solis and Jason Hall as they examine rocks for aquatic moth larvae.

Granted, delicate butterflies with their jeweled wings garner far better press than their allegedly drab cousins in the taxonomic order called Lepidoptera. They probably always will. But moths will always one-up butterflies by their sheer numbers. According to a 2016 checklist, butterfly species in North America north of Mexico totaled 836, while moths tipped the scale at 11,930.

In Texas, moth species number a less daunting 4,672, according to a 2018 checklist compiled by two Texas moth experts, the late Ed Knudson and the late Charles Bordelon. Biologists and moth enthusiasts break moths into two subgroups: tiny micro-moths and larger macro-moths. That said, moths vary in size from fairy moths that measure less than 2 centimeters long (conversion: 0.8 inches) to a giant silkworm moth — the cecropia — that has a nearly 6-inch wingspan.

Unless distinctly marked, the abundance and diversity of moths can make exact identifications challenging. Some important clues include a moth’s size, shape and at-rest posture.

Basic characteristics can also indicate a particular moth family. Spindly legs and a T-shape point to a plume moth. Grass-veneers come in small, tubular bodies with fuzzy snouts (labial palps). Small, chunky bodies with rounded wings held in a tent position and curled-up abdomens are slug moths. Flannel moths sport fur-coated bodies with velvety wings, fuzzy legs and long feather-like antennae.

Owlet moths, the largest family with more than 900 Texas species, are triangular in shape. They can be drab or intricately patterned. Growing from inchworms, Geometrid moths, the second largest family with more than 500 Texas species, have slender bodies and broad wings that are sometimes crossed with wavy lines and held away from the body or vertically when at rest.

Photo © Charlie Floyd/Dreamstime.com

GIANT LEOPARD

(Hypercompe scribonia)

Photo © Tony Gibson/Dreamstime.com

BLACK WITCH

(Ascalapha odorata)

Photo © Melinda Fawver/Dreamstime.com

SNOWBERRY CLEARWING

(Hemaris diffinis)

Some moths are remarkable mimics. At first glance, the lesser grape borer looks like a paper wasp. Orange-tipped black antennae and an orange-ringed black abdomen mark the Texas wasp moth, while the snowberry clearwing poses as a bumble-bee wannabe. The shining urania moth — velvety black with metallic green lines — passes for a swallowtail. As for bird-dropping moths, they resemble exactly what predators won’t eat: bird poop.

In nature’s food web, moths play a vital role.

“They are absolutely crucial to fish, birds and many rodents,” says Ric Peigler, a biology professor at the University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio. “Spring’s flush of caterpillars is important for birds that are feeding their young. Waterfowl eat aquatic insects, including aquatic moth caterpillars. Moths are also the primary food of bats.”

As a whole, winged adult moths cause no damage in yards, kitchens and closets. However, the larvae of a few can be pesky. For example, the caterpillars of clothes moths feed on fibers and fabrics. Other moth larval pests include the cotton bollworm (also called corn earworm), European corn borer, squash vine borer, corn earworm and fall armyworm.

Some larvae can sting, such as the io, tussock, spiny oak-slug, saddleback and buck moth. One of the most toxic caterpillars is the puss (also called an asp), the larvae of flannel moths. When touched, tiny, hollow spines on their furry, teardrop-shaped bodies fill with venom, break off and jab into a victim’s skin, triggering a painful or itchy rash. Severe reactions can lead to nausea, stomach pain or headache.

Photo © Charlie Floyd/Dreamstime.com

CECROPIA

(Hyalophora cecropia)

Photo © Cathy Keifer/Dreamstime.com

POLYPHEMUS

(Antheraea polyphemus)

Photo © José Madrigal

WHITE PALPITA

(Diaphania costata)

Photo © Sheryl Smith-Rodgers

Researcher Jason Hall photographs live moth larvae to document the little-known aquatic species he and his wife found at Spring Creek near Boerne.

Not surprisingly, moths occur all over the state.

“Some are adapted to the deserts of West Texas, while others inhabit the forests of East Texas,” says Peigler, who studies wild silkmoths worldwide. “Some moths, such as the beautiful Grote’s buck moth, are endemic only to the Edwards Plateau and nowhere else.”

Back at Spring Creek, Solis brings up another rock and turns it over. With tweezers, she gently probes the algae.

“These caterpillars have developed very rare and difficult adaptations to breathe underwater,” she tells me. “Some have gills like white hairs that exchange oxygen with fast-moving water. Others form plastrons (bubbles) around their body and float on the water. Others make cases out of duckweed or bore into water lily stems. Some feed on aquatic plant rootlets or tree roots.”

Solis, a native Texan from Brownsville, is one of the world’s leading authorities on crambid snout moths. Her husband, who was born and raised in England, specializes in metalmark butterflies. Both work as research entomologists at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. She also works for the USDA’s Systematic Entomology Lab.

On a daily basis, Solis examines caterpillars and moths found by federal inspectors on agricultural imports. Her confirmation of a pest species can mean an imported commodity must be fumigated or destroyed to prevent the insect from entering the U.S. The pests fall within her research specialty, crambid snouts. A few caterpillars in this group feed on crops, forests and stored food products, such as nuts and wheat.

As mentioned above, some crambid larvae are also aquatic. As part of her job, Solis may be asked if an aquatic caterpillar found on imported aquarium plants occurs in the United States.

“In order to answer that question, I have to know which ones already exist in the U.S.,” she explains. “It’s about drawing from accumulated knowledge from all over the world.”

Her quest to learn more about native aquatic species ultimately linked her with Cain, an Austin attorney with no formal science training. After his retirement in 2006, he and his wife, Ann, moved to their Boerne-area property, where Cain spent hours exploring its grassy uplands, limestone cliffs and riparian habitats along Spring Creek. Intrigued, his study interests grew from native plants and songbirds to butterflies on wildflowers and moths at his porch light. He often photographed what he found and shared his images with like-minded friends. (He still does.)

Photo Courtesy of Jerry Powell / Essig Museum

AILANTHUS WEBWORM

(Atteva aurea)

Photo Courtesy of David Wagner

LACTURIDAE

(Lactura rubritegula)

Photo © Carol Wolf

SPANISH

(Xanthopastis timais)

In 2012, Cain’s photo of a moth caterpillar reached biologist David Wagner, a researcher at the University of Connecticut and author of Caterpillars of Eastern North America: A Guide to Identification and Natural History. Soon Cain was photographing and rearing caterpillars for Wagner, who later sent graduate students to collect moths on the Cain property and even made a visit himself in 2017. Research gleaned from the trip enabled Wagner and associate Tanner Matson to identify a new moth (Lactura rubritegula), thanks in part to Cain’s contributions of photographs and specimens.

Ever curious, Cain sent photos of what he believed were aquatic moths to an invertebrate biologist with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Via email, the images were forwarded up the expert ladder to Solis.

“I can tell a forest’s health by its moth species,” she says. “When I saw Delmar’s moths, I could tell immediately what the habitat was like. I knew his place was special. And it is. Spring Creek has the least polluted water system in this part of the world. That means moth diversity will be higher here.”

Meanwhile, armed with a net, Hall wades into deeper water and scoops up aquatic plants, which he examines for larvae. Another net-full brings up a white moth clinging to a submerged stick. Cain un-lids a specimen vial and holds it out to Hall.

“At dusk, the moths fly over the water, looking for mates,” Solis says. “Only females may go near or under water to lay eggs.”

Two hours later, the pair unloads their backpacks at Cain’s house, where they’re staying overnight. At a small table in their guest quarters, Hall sets up his Canon digital camera on a focusing rail. Using a macro lens and ring flash, he captures images of live caterpillars for several hours. His detailed photos will further document these little-known aquatic species.

Inside the Cain home, Solis pins moths at the dining table. Using forceps, she pushes a stainless-steel pin through the insect’s body, then pushes the pin into the slot of a wooden pinning board. With forceps and a long pin, she meticulously spreads the moth’s fragile wings onto the boards. Next she covers the wings with thin strips of paper, which she pins in place. When filled, the board will join others in a briefcase-sized metal box for later transfer to the Smithsonian Institution.

Finally, some specimens go into liquid nitrogen storage canisters for shipment back to the institution. At the lab, Solis will analyze body tissues of the terrestrial adults, and aquatic larvae and pupae.

“With DNA studies, we can link together the different stages of a species, which is much faster and easier than rearing a caterpillar to an adult to nail down the species,” she explains. “We’ll also deposit this genetic material in the Smithsonian’s Global Genome Initiative, which endeavors to sample the genes of every organism on earth.”

All told, Solis collected 12 moth species on the Cain property, three of which were aquatic.

“As a pilot project, my time in Texas was very successful,” she says. “Our fieldwork was extremely important for planning future studies. I’m already planning another trip to Delmar’s creek because there are still many unanswered questions about the biology of aquatic moth species. Citizen scientists like him who take insect photographs are such a huge help in broadening our research.”

Seated at the dining table, Cain smiles.

“I sent one email and hit the jackpot when Dr. Solis asked to collect here,” he says. “We’re looking forward to her return. In the meantime, I’ll keep chasing and photographing Texas moths.”

Sheryl Smith-Rodgers uses iNaturalist to document moths and other wildlife at her home.