Earl Nottingham | TPWD

Off the Pavement

From the frontier to the front line, Texas game wardens have answered the call for 125 years.

For 125 years, “Law Enforcement Off the Pavement” has been more than a motto for Texas game wardens — it’s the core of what they do day and night to protect Texans and the state’s natural resources.

In a state this size, it’s a massive, coordinated operation. More than 550 game wardens (stationed in all 254 counties) patrol about 11 million miles of roads and coastline and everything in between.

“Our game wardens have a long and storied history of conservation law enforcement in our state, beginning with the first wardens hired to stop the overexploitation of oysters in Galveston Bay,” says Carter Smith, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department executive director. “I am proud to say that our game wardens are still working to protect oysters in Galveston Bay, plus a whole lot more, 125 years later.”

TPWD LE Photo Library

Texas game wardens around 1911.

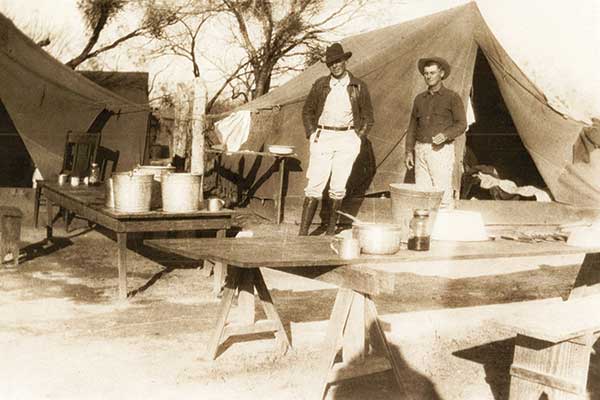

TPWD LE Photo Library

A game warden camp in 1929.

TPWD LE Photo Library

The first game warden graduation class at Texas A&M in the 1940s.

The Frontier Years

Utilizing a variety of new techniques, teams and technology, the game wardens we know today have evolved dramatically since the first ones were commissioned in 1895.

During Texas’ frontier days, most people lived in rural areas and spent their days ranching and farming; Texas became a leading producer of cotton and cattle at the time. Major oil deposits were discovered in Texas in 1894, and oil became a profitable industry.

In the midst of this boom, Texans enjoyed the state’s bounty of game animals without limit. The resulting overharvesting caused pressure on the fish and wildlife populations, so the Texas Legislature established new regulations to help manage these resources.

The state’s first game law in 1861 established a two-year closed season for quail. Thirteen years later, state fishing regulations were adopted on coastal seining and netting. There was an immense amount of local pushback — in 1883, 130 Texas counties claimed exemption from all game laws.

The Texas Legislature stepped in to create a regulatory office, the Fish and Oyster Commission, in 1895. I.P. Kibbe was appointed commissioner by the governor; a handful of deputies became law enforcement agents to help regulate the harvesting of shrimp, fish and oysters in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Legislature expanded the oversight of the Fish and Oyster Commission to include the responsibility of managing game animals and laws in 1907, and the agency morphed into the Game, Fish and Oyster Commission.

By 1919, six game wardens enforced the regulations protecting fish and game in Texas; in the next decade, the number grew to 80.

Radios were introduced in the 1930s, a revolutionary way for wardens to communicate and conduct law enforcement. Most game wardens patrolled on horseback or in personal vehicles. They were outfitted with their first official uniforms in 1938.

In 1946, the first game warden cadet class graduated from a school held at Texas A&M University. The class consisted of 17 cadets, who studied wildlife law and more. By the end of the 1950s, 210 game wardens were patrolling the state.

As the commission became the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in 1963, life as a game warden evolved as well. Game wardens were assigned state patrol cars with the comforts of automatic transmission and air conditioning, along with firearms and other equipment.

The 1970s ushered in a new era for game wardens as they received peace officer status. This new designation allowed game wardens to enforce not only game laws, but all state laws. They also began patrolling for violations of the Water Safety Act, helping Texans safely recreate on the water.

Earl Nottingham | TPWD

Women join the ranks

Thirty-nine women are Texas game wardens today, serving in counties across the state.

In the 1920s, Cordelia Jane Sloan Duke became the first (appointed) female Texas game warden. The land around her homestead was designated as a wildlife sanctuary that annually hosted thousands of wild ducks.

In 1979, Stacy Bishop Lawrence became the first female game warden to graduate from the Texas Game Warden Academy. This was one of the first years the academy was held in Austin.

“The first time I applied I was rejected, because I would not have been 21 by graduation,” Bishop Lawrence says. “I had to wait almost four years for the next application process. Back then, TPWD received approximately 3,000 applications for 30 to 40 positions. Competition was brutal. Somehow, someway, I made it through the application process.”

In September 1978, Bishop Lawrence began her study with the 33rd Game Warden Academy; only three of the 38 cadets were female.

“The training was tough,” Bishop Lawrence says. “Unfortunately, one of the females quit soon after training began; the second left about a third of the way through.”

Alone in a class full of guys, she says she was “too stubborn” to try to be friends.

“It took one of my classmates to break the ice, and the door was opened,” she says. “To this day, I deeply appreciate the friendships and the camaraderie that evolved.”

Modern Techniques

Through the remaining decades of the century, the Texas game wardens not only grew in numbers, but also in patrol techniques. They began using new methods (like using deer decoys to catch poachers), new defensive tactics and new handcuffing procedures. New patrol vessels enhanced their presence on waterways, and game wardens were equipped and trained to use new firearms for the first time.

The new training and equipment came just in time, as modern game wardens face new and increasingly complicated duties. Although wardens continue to focus on conservation law enforcement, they have adapted to stay at the forefront of all modern law enforcement strategies.

Game wardens are now “The Texas Navy,” designated as the primary enforcement agency in Texas public waters, enforcing resource violations, promoting boating safety and investigating boating accidents.

The Special Investigations Unit focuses on conducting web-based investigations of illegal wildlife trafficking. Through the Operation Game Thief program, people who notice illegal wildlife activity online can submit tips for investigation.

Game wardens have always assisted in search-and-rescue efforts across the state, but new technology and techniques increase their effectiveness.

TPWD incorporated a new K9 team in 2013 to assist in search and rescue, cadaver search, narcotics enforcement and detection of illegally taken or smuggled game and fish.

The new game warden helicopter, added in 2014, has a rescue hoist, thermal imager, searchlight, public address system, satellite communication and night vision. In 2018, game wardens expanded their arsenal further with a new search-and-rescue drone.

Chase Fountain | TPWD

Game wardens have diversified their ranks and expanded their tools and training over the years, including swift-water rescues, a new helicopter, specialized water patrols and a K9 unit.

Chase Fountain | TPWD

Earl Nottingham | TPWD

Chase Fountain | TPWD

When Disaster Strikes

New training techniques focusing on swift water have enabled wardens to respond during floods and natural disasters.

These skills were instrumental when wardens responded to some of the most destructive natural disasters to strike the Gulf Coast, including hurricanes Katrina and Harvey.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans. For several days, the powerful storm flooded the city. On August 30, wardens crossed the Louisiana state line to help, marking the first time Texas game wardens were deployed for disaster relief out of state. Game warden Chris Davis was part of that first wave.

“We really didn’t know exactly where we were going, where we would stay or what the conditions would be like,” Davis recalls.

The wardens used 4X4 trucks and shallow-water vessels to reach and evacuate residents in the hardest-hit areas of New Orleans. By the end, more than 100 Texas game wardens rescued more than 5,000 people from their homes.

“We witnessed the devastation of a historic city and how it brought out the best and worst of human behavior,” he says.

Davis says the wardens hold on to personal stories about the people they met, and still think about the people rescued and the ones who didn’t make it.

“I’ll never forget the dedication and tireless efforts of each and every game warden who answered the call,” Davis says. “They persevered through unimaginable challenges and made a difference when it counted the most.”

Twelve years later, it was Texas’ turn to feel the wrath of Gulf weather. Hurricane Harvey hit the Texas coast near Rockport, causing widespread flooding across most of the state’s coastline. Game wardens leapt into action to help with search-and-rescue efforts throughout Texas. When it was over, 368 wardens had rescued more than 12,000 from floodwaters.

“Harvey was originally set to hit my hometown of Corpus Christi,” says game warden Carmen Rickel. “I had spent the day before preparing my own home, and helping my neighbors board up their houses. I worried about getting my husband to a safe place and making sure our extended family was prepared.”

Rickel’s unit was deployed first as part of the Incident Response Assessment Team, assigned to the hardest-hit areas to report the immediate needs of that community to the State Emergency Operation Center.

“We drove into Rockport and it was still dark and raining,” says Rickel. “As the daylight started to creep up on us, so did the magnitude of the devastation. We worked all day into the night in Rockport and by then, Houston was literally drowning.”

Her unit left for the Houston area the following morning.

“We arrived in Fort Bend County to never-ending rain and thousands of people needing help and evacuation,” she says.

Rickel says the wardens never stopped until every person was safe.

“I drove home at the end of the week in awe of my partners and with a new respect for the resiliency of our people in this great state,” Rickel says. “The most important lesson learned is not about responses and tactics but that when we are hit the hardest, the police and the people come together as one.”

Meet Col. Chad Jones

The chief officer of the Texas game wardens achieves the rank of colonel. Many of the past colonels have dedicated their time in leadership roles toward striving to push the organization forward. Colonels Pete Flores, Craig Hunter and Grahame Jones brought new elements into the role in recent years.

“Throughout their history, our law enforcement team has been well served, and well led, by an exceptional group of colonels who have set the bar high for those seeking to follow in their footsteps,” Smith says. “Collectively and individually, their leadership has been defined by their unassailable integrity, altruistic service, deep resolve and inexorable commitment to doing what is right and best to protect the bountiful natural resources of our state.”

In July 2020, game warden Chad Jones became the latest director of the Law Enforcement Division for TPWD. Col. Jones became a game warden in 2004 and has held duty stations in Brazos and Trinity counties. He led the Forensic Accident and Reconstruction Team and served at the Game Warden Training Center and in Uvalde, Corpus Christi and the Pineywoods region of East Texas.

“For 125 years, Texas game wardens have been the example for agencies across the nation to follow when it comes to a successful conservation law enforcement model,” Jones says. “We’ve been fortunate to benefit from a long line of exceptional service-oriented leaders who promoted inspiration and innovation throughout our culture.”

During his tenure as a game warden on patrol, Jones says he has gained insight that will assist him in leading an ever-evolving law enforcement team.

“We continually strive for an inclusive, diverse, accountable and highly trained workforce,” Jones says. “We will represent all Texans and continue to provide proactive, accountable, professional conservation law enforcement off the pavement.”

Looking ahead, Jones hopes to build on the strong foundation laid by his predecessors.

“There will never be a caprock on this foundation,” said Jones. “It will never be cemented with ‘Chad Jones stood here.’ We strive to have those following in our footsteps lay down an even stronger foundation for the next generation. We will continue to strive, to inspire, to never settle for less and always look to improve.”

Stephanie Salinas Garcia works in the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department press office.

Related stories

» Like this story? If you enjoy reading articles like this, subscribe to Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine.