Illustration © Dunicheva | dreamstime.com

Seeds of Knowledge: Ynes Mexia and Maude Young

By Louie Bond

“In the scientific world of the day, there was still a strict division between ‘botany’ (the study of plants by men) and ‘polite botany’ (the study of plants by women) — except that one field was regarded with respect and the other was not — but still, Alma did not wish to be shrugged off as a mere polite botanist.”

– Elizabeth Gilbert, The Signature of All Things

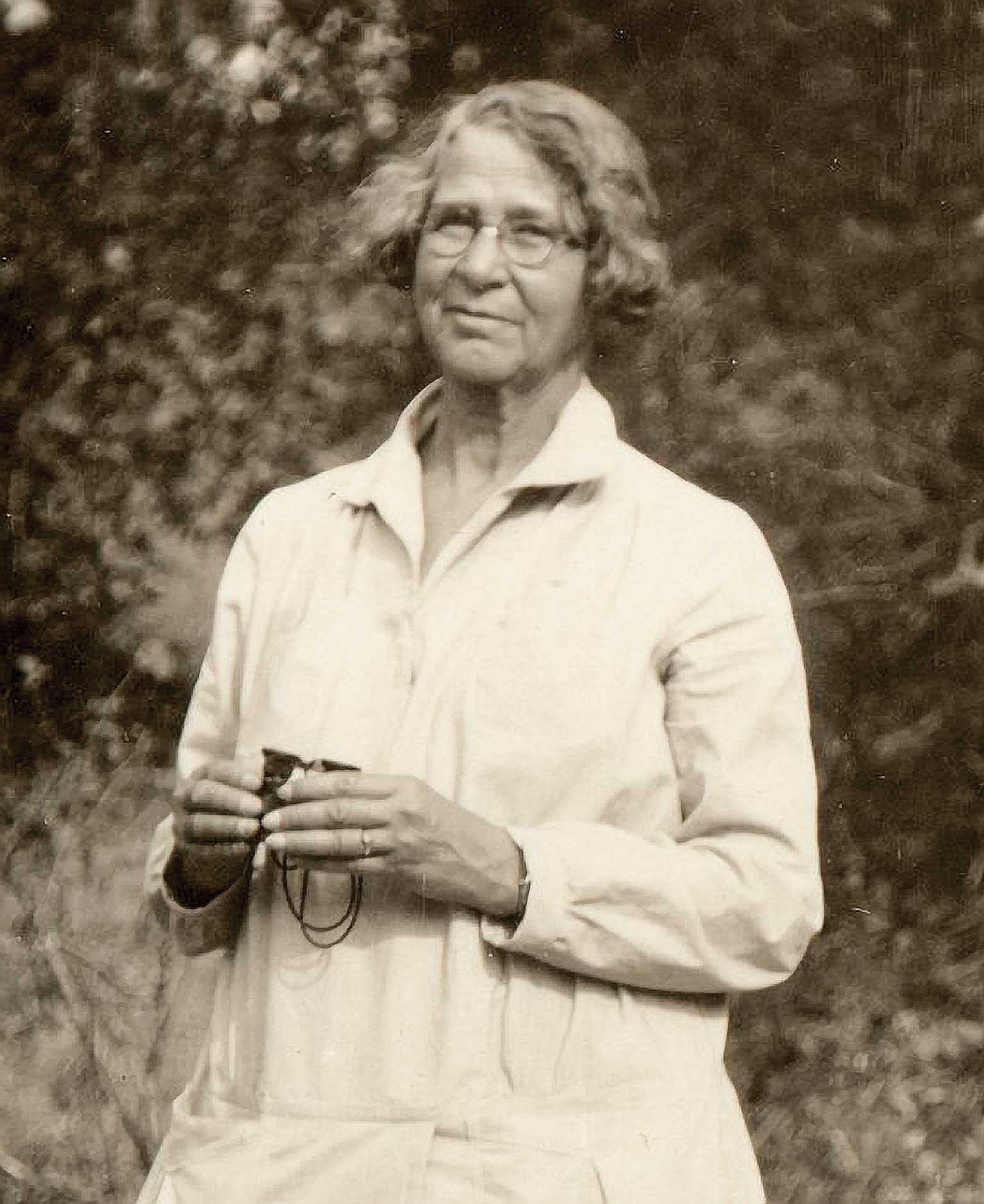

Ynes Mexia, who didn’t start formal study of botany until her 50s, became one of America’s most accomplished plant collectors.

Blazing Her Own Trail

The path of a Texas “wild woman” of conservation is never easy and rarely linear, and Ynes Mexia exemplifies this notion. Though her family name graces a Texas town, her time here was limited, and she came to her passion for plants late in life, after two marriages and a nervous breakdown. Yet Ynes’ achievements as one of the greatest botanists of her time and her family’s long-lasting ties to Texas give us the right to brag.

Ynes’ botanical treks through Latin America made her a legend. In her lifetime, she collected at least 150,000 plant specimens, discovering as many as 500 new species and two new genera. One genus, Mexianthus, a type of sunflower in Jalisco, was named after her, as were at least 50 species.

Much of Ynes’ early life is shrouded in mystery, leaving us wondering how long she lived in Texas because accounts vary. But Ynes’ ties to Texas run deep: The town of Mexia was named for the Mexía family, who in 1833 received an 11-league land grant that included the townsite. While Ynes was born in Washington, D.C., in 1870, her American mother and Mexican diplomat father divorced when she was 3. Her mother moved the children to Limestone County, but it’s unclear how long young Ynes lived and studied in Texas before attending school in Maryland and later following her father to Mexico City.

Ynes wanted to become a nun but changed her mind when her father threatened to cut her out of his will. After his death, she successfully fought her father’s mistress in court for that inheritance, then married twice in rapid succession. Ynes’ first husband died after a long illness; she divorced her second husband in 1908 after he mismanaged her poultry business in Mexico City.

In the following months, she fell apart both physically and emotionally, and moved to San Francisco to seek medical care. For the next decade or so, in her 40s, Ynes found solace in the beauty of Northern California’s mountains, where she hiked on excursions with the Sierra Club. By 1921, at the ripe old age of 51, she enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, older than the other students but cheerful, as tough Ynes didn’t care what anyone thought of her.

Ynes soon took off on scientific expeditions, first to Mexico in 1925, where she quickly abandoned her classmates to work on her own. She stayed for two years, collecting 1,500 specimens and making a name for herself, never completing her degree. She spent the next decade traveling solo (at a time when women didn’t do this) across North and South America. Clad in pants and astride a horse, she loved sleeping under the stars. She traveled by canoe on the Amazon to its source in the Andes and collected plants throughout Alaska.

Photos from those times show daring Ynes in action: legs dangling over the rim of the Grand Canyon, cross-country skiing in a long dress and tiptoeing across a log spanning a chasm. These adventures, along with the serenity of solitude in the wilderness, finally healed Ynes’ broken spirit. She became ever more bold and fearless, totally dedicated to her passion, unconcerned about breaking society’s norms.

“A well-known collector and explorer stated very positively that ‘it was impossible for a woman to travel alone in Latin America,’” Ynes wrote. “I decided that if I wanted to become better acquainted with the South American Continent, the best way would be to make my way right across it. Well, why not?”

A mid-1930s Ecuadorian trip led Ynes on a mission to find a tall tree, the wax palm, that tolerated extreme cold and thrived at high elevations. U.S. biologists needed a specimen, and Ynes was determined to bring one back. The trip’s challenges included the ingestion of poisonous berries (which the indigenous people helped her bring back up with a chicken feather down the throat), earthquakes, terrible mud, steep ravines and more. Through it all, Ynes was content, collecting rare specimens and taking it all in stride. Her efforts paid off when she negotiated a hair-raising path and found herself face to face with her holy grail, the wax palm, its white trunk rising like a monument to her struggles.

“I photographed the great spathe and flower-cluster, so heavy the two men could hardly lift it; made measurements and notes; and took portions of the great arching fronds,” she later wrote in the Sierra Club Bulletin. “Then we started on the long journey back, arriving after dark, very tired, very hot, very dirty, but very happy.”

During a 1938 expedition to Mexico, Ynes fell ill; she was diagnosed with lung cancer and died a month later. She left much of her estate to environmental causes.

“All who knew Ynes Mexia could not fail to be impressed by her friendly, unassuming spirit,” wrote William E. Colby in a Sierra Club memorial, “and by that rare courage which enabled her to travel, much of the time alone, in lands where few would dare to follow.”

Maude Jeannie Young was an author, teacher and botanist. She served as state botanist and published the first textbook on Texas botany.

Flags and Flowers

Texas’ other noted 19th-century female botanist followed a more traditional route to her career than Ynes Mexia. But Maude Jeannie Young (born Matilda Jane Fuller) was also ahead of her time, serving as state botanist and publishing the first textbook on Texas botany.

Born in North Carolina in 1826, Maude moved with her family to Houston in 1843 (her father became mayor) and married a doctor four years later. When he died after nine months, Maude moved back in with her family and delivered their only child, a son named for his late father.

During her early career, Maude wrote poems, fiction and essays that were published in the Houston paper and various magazines. The Civil War ignited Maude’s patriotic fervor, changing her writing topics to those she deemed inspirational for Confederate soldiers, using pen names like The Confederate Lady and The Soldier’s Friend. Maude, who was related to Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg, also designed a flag for her son’s brigade, Hood’s Texas Brigade. Gen. John Bell Hood designated it as their official flag at the battle of Gettysburg.

After the war, Maude became interested in botany and taught in Houston’s public and private schools. Natural history found its way into her writing, and she penned articles on singing mice and forest culture, encouraging conservation. She became one of the first Texans to write a textbook, Familiar Lessons in Botany, with Flora of Texas in 1873 as state botanist. The book was more than 600 pages long and was used by Texas students for years.

Maude died in 1882, and her son became the caretaker of her works. Sadly, her herbarium of ferns and flowering plants and her writings were all lost in the great Galveston hurricane of 1900.

In honor of the ratification of the 19th amendment 100 years ago, we’ll spotlight 20 Wild Women of Texas Conservation during 2020.

Related stories

» Like this story? If you enjoy reading articles like this, subscribe to Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine.