The Fisher King

Despite raucous storms and melted gear, a fisherman is born at Lake Livingston State Park.

By Barbara Rodriguez

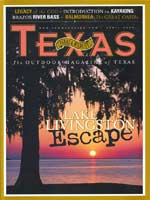

Halfway through fall break I decide we need a family getaway. Lake Livingston State Park is a good 4 1/2-hour drive from Fort Worth, but I figure if we pack that night and leave the next morning we’ll have two nights and one full day in the 635-acre park.

But before committing to the road trip, I take time to study the weather forecast. Hurricane Ivan is spinning back onto the scene in Louisiana, just close enough to hurl something nasty toward Southeast Texas. I decide a 30 percent chance of rain means the odds are in our favor. And really, how much spirit dampening can a has-been hurricane do? Given the short departure schedule I abandon checklists and embrace spontaneity. I even let my 7-year-old pack his own diversion bag (thankfully, I find and remove the hamster before things take an ugly turn).

On the Road

We load up and head out the next morning. It’s unseasonably warm and the long stretch toward the Big Thicket is overcast, not gloomy. We’re anxious to arrive and select our hut-away-from-home.

Maybe too anxious.

About an hour out, Elliott starts asking if we’re there yet — every 10 minutes. It is a self-parody that is not amusing for long. I hand him his backpack and encourage him to find something to occupy himself. He grows quiet. When I look back he is wrapped head to toe in a quilt. The binoculars protruding from the swaddling offer the only proof it’s occupied. He begins sighting and counting birds, a somnolent sport that lapses into a nap until just past Huntsville, when we cross the 84,000-acre reservoir. Bursting from his cocoon Elliott gasps, “That’s no lake, that’s an ocean!”

Encouraged by his newfound enthusiasm, I begin regaling him with tales of record-setting catfish, black crappie, lunker bass. His only concern is that his dad will have to help him reel in these monsters.

Sunday Afternoon

We arrive at the campgrounds just after noon Sunday. Happily enough, we have our choice of the 10 scattered tin-roof-and-timber shelters on stubby stilts. Although it is still early and very warm, the shaded half-court campground is deserted. So many available lakeside cabins make for a hard decision. Do we want the one mere steps from the parking lot, high on a swell with unobstructed views of water? Yes, I decide we do. Certain that a tidal wave of campers will arrive any moment, we rush back to the ranger’s station, stake our claim and return to settle in. But by then our original choice doesn’t look so good to me. It is gorgeously situated — really, all of the loblolly-and-oak-shaded shelters are inviting — but I decide that as the weather is uncertain, and as two walls of the shelter are floor-to-ceiling screens, our first choice might prove too chilly at night. True, there is a sleeping loft, but this has already been staked out by our son, who intends to pitch his tent on the platform. He is sure to be cozy in his sky-high Bedouin kingdom, but as the sliding barn-like doors on the sides of the shelters cover only half the screens, we groundlings won’t be able to shut out the rain completely — should it come.

Hundreds of staples in the woodwork give witness to how cool-weather campers past have made do. I make a mental note to add plastic sheeting and a staple gun to my packing list. Then I make my husband reload and relocate our stuff to a cabin which seems less exposed to the elements. This shelter is set down off the road and has a grated fire ring almost on the lake. Best of all there are fishing opportunities mere steps away from our door. Jurgen humps our gear down the winding wooden ramp with little snarling (attractive wooden wheelchair ramps that zig and zag between cabins give the campsite a sort of treehouse feel). No doubt it is more of a haul to our new cabin, but father and son are of good cheer until I want to move the picnic table. That’s when I hear Jurgen snort through his nose.

By the time we inform the rangers of our change of address, it occurs to me that if we are to saddle up this trip we’d best make a dash for the Lake Livingston Stables. The popular park concession rents horses daily in the summer, but after Labor Day the two-mile guided rides are available only on a limited weekend schedule. We arrive in time to see the rump of the last horse disappear into the forest. Hopes for an early morning trot to breakfast or an indulgent sunset-and-steak trail ride are dashed; the horses won’t be back until the following weekend.

It is my turn to snort a few sparks, but Elliott is all smiles. Now there are no horses standing between him and the fish. To sweeten the pot, I promise him his first encounter with live bait. We head to the camp store to buy nightcrawlers and minnows. Beyond the bait offerings, the mini-marina has an inventory a kid’s (and this gal’s) gotta love: neon jelly flip flops, Chocolate Soldiers, Jiffy Pop, Hershey bars and ice cream. And if the adjacent lighted pier and wooden observation tower don’t offer adventure enough, you can rent paddle boats, bikes and canoes. We promise to avail ourselves of all these amusements the next day. For now, a melted butter sunset is in the offing, we have filet mignons in the ice chest and all is right with the world. Let the fishing begin!

Almost.

Apparently Elliott’s rod has been stored away with his favorite “fish attractor” on the line and the bail open. I immediately disavow the nested heaps that web two of three rods, hand Elliott the one that’s still functional and abandon my put-upon husband to rigging duty. The paved walking path that hems the lake along the eastern edge of the park makes for easy access to strolling and fishing. We head off, but not so far that we don’t hear Jurgen’s howl when the rig he has just cleared and baited falls into the campfire, instantly melting away the line and warping the rod. Having vented his angst, the poor man falls back to his Sisyphean task.

Teaching Elliott to bait a hook promises to be less trying. I hadn’t skewered a minnow in years but the slippery fish and the cool updraft from the bucket evoke my childhood so vividly I expect to hear my brother calling me Squirrel Head as he ridicules my technique. Elliott, who can’t resist a shot at scooping up the little fish with his hands, is unprepared for how difficult they are to catch. He’s delighted when he comes up with one wriggling inside his grubby fist. As I show him how to place the hook he offers the fish an apology. Next, of course, he asks to keep one as a pet. Keeping them alive to fish another day is my goal, especially having seen the filthy hands that Elliott keeps plunging into their water. To give them a break I throw the minnow bucket into the lake. I swear I thought the rope lying at my feet was actually tied to the bucket at the time.

Jurgen is called from his rigging duties to fetch the minnow bucket. The man is a saint.

At least one of us is having a great time. But when we finally join Elliott we fish enthusiastically, albeit without success, until it starts to get dark. The black crappie Lake Livingston is famous for will have to wait. We call it a day, content to know we have all of tomorrow for fishing, hiking and boating.

On the way to the bathhouse Elliott sights a tiny leopard frog in the beam of his flashlight. When he captures it, a long naming session follows. At last he hits on the obvious. Sort of. “He’ll be Froggy. Froggy Wolfgang Oldenburg, since he’s my brother. Well, his name will be Frederick. We’ll call him Froggy.” I don’t worry too much about losing my dishwashing basin to F.W.O. for long; Elliott has a good history of catch and release. That is before he suggests making Froggy’s accommodation more permanent. “I know!” he says, suddenly inspired, “Let’s keep him with the piranhas!” His father and I look at each other blankly. Malapropism is rampant in our family. I remember that Jurgen once excitedly pointed out an opossum while shouting, “Look, an octopus!” But then, his first language is German. “You know…” Elliott says, emphatically pointing at the minnow bucket, “We’ll keep him with the salmon.” That’s when it occurs to me that his fishing education may be a little patchy.

By bedtime a stomach aching number of marshmallows have been roasted and consumed in a ritual that includes this conversation: “Dad, how do you like yours?” “Brown.” “Is that after black?” At the time Elliott is trying to douse with spittle one that is now fully aflame. Brother Froggy has been released to a lengthy farewell-and-good-fortune speech after a misguided attempt to feed him a night crawler. Before turning in, Jurgen inspects the fishing gear. He tries to keep his voice at an even pitch when he asks me how it is that all the rods are once again hopelessly snarled. I don’t tell him about walking under a tree with my rod held high as I raced to stop Elliott from whirling his bobber around the end of his rod.

We settle in to sleep like the dead. In his sky kingdom Elliott has a screened view of the lake. I call up to him: “What was the best part of the day?” “I got a new pet,” he answers. “The only bad part of the day was that I had to let him go.” As we drift off the cricket song is punctuated by the occasional pling of an acorn on the tin roof. Jurgen murmurs, “Did you bring the French press?” I imagine he’s thinking he’ll need caffeine early and frequently if he’s to spend another day of battling Gordian knots.

Monday, Monday

Day two is filled with promise. Elliott gulps breakfast, anxious to tackle the technique of worm fishing — or play with the worms. Jurgen and I linger over our French press coffee. Across the water an island shimmies in the distance. We talk about how comforting it is to pad around the campground on the soft pineywood soil; sight what might be a swamp rabbit; take time to breathe deeply; and express gratitude that so far we have been assaulted by nary a mosquito. Elliott heads a little farther down the walking path after each cast, until he is out of sight. I know his destination to be a portion of the shore where the walkway has collapsed in a mudslide. His instinct that fish will like this runoff area gives me hope that he has his grandfather’s fishing genes. But when I follow him I find him tugging at a line that is tautly horizontal, as he struggles to pull free of a snag of logs. I’m glad Jurgen isn’t here to see this. Then I realize that in fact he is hauling in his very first fish, a nice-sized sunfish. He is so excited he has completely forgotten the reel and is attempting to drag the fish in.

He is ecstatic when he sees me. “Mom! Mom! I caught a fish. All by myself. I have to show Dad.” He beams at me, a goofy gap where his front teeth should be. His eyes are glistening. “I am so proud of myself I could cry!” he says, and for a minute I think we both might. I hug him tight. In that moment I become his bait slave. As fast as he can catch the fish I skewer up the nightcrawlers. He quickly fills a stringer with pan fish. “Are you proud of me?” he asks, more than once. There are no words, I tell him. I watch him as he masters the language of a bobber, no longer jerking the worm out of the eager mouths, but letting the bobber disappear and begin to swim before he gives the line a little tug and then, with his signature whiplash, sets the hook. He even remembers to crank the reel. He has been listening to me. I am amazed.

At lunch we take a break for a picnic and Elliott is unusually quiet until he archly says, “Say, anybody caught anything yet?” A beat, then, “Oh, yeah, I did.” He cackles like a madman at his own joke. Who has time to catch fish when they are in baiting servitude to the Fish Master? Jurgen, reveling in a brief respite from rigging, has managed a few casts, but without luck. “I’m not stopping till I catch eight — or we run out of worms,” Elliott announces. He catches eight, and we run out of nightcrawlers. We’d only bought a dozen. His fish-to-worm ratio is excellent. Elliott smeared with jelly, dirt and his own share of worm guts is as joyful as only a dirty boy can be. When a squirrel runs right across his feet he cocks his head and whoops that it’s his lucky day. Mine, too. All morning I have been happily reminded of a childhood spent with worm dirt under my nails.

We’ve talked enthusiastically about frying up his mess of fish, but suddenly, his streak broken, he says, “Those fish I caught… I don’t really want to eat them. I want to let them go.” And he does, to a great cacophony of birdcalls. The water facing our campsite is studded with jagged tree trunks rising and falling in a silvered march across the horizon like so many mismatched pylons. Each is now topped by a bird, seagulls mostly, ready to play an elaborate game of squawk-and- switch presided over by a solemnly regal great blue heron. The gulls mob one another, then flit away cajoling and chortling, as if to say “Look over here, look over here.” Any bird simpleminded enough to follow the shill immediately loses her perch. This continues for 40 minutes as the sky boils up into great lumps of blackened marshmallow clouds.

By 2 p.m. the wind is whitecapping the lake and the storm begins pelting us with hard, cold pellets of rain. The birds abruptly end their game and take flight. We bolt for shelter as the winds begin gusting. Remarkably, until the rain makes it impossible to continue, a very single-minded park worker doggedly attends his task of leaf blowing, seemingly oblivious to the fact that he is not the creator of the whirlwind surrounding him.

We have positioned the barn doors of our shelter at the head and foot of our bedding, and I think how nice it would be to have a couple more plastic tablecloths to extend the coverage. I know Elliott’s bed will stay dry in his tent in the loft, but ours will no doubt get misty from the blowing rain. Still, there’s nothing to be done now. And as much as we’d all looked forward to hiking the Pineywoods Trail loop around the duck pond, there is a strange comfort in the lack of options now available. Boats are out, bikes and hikes impossible, but we cheerfully hunker down to read to one another from various books, play cards, snack on chips and hot sauce. It’s like being comfortably sealed in the miniscule hut inside a snowglobe, the weather whirling all around us. Around dinner time the rain breaks. The birds return and the sky runs with blue-on-blue rivulets, a watercolor streaking off the edges of the sky. We trot to the edge of the campground to walk out to the boat docks above a small cove and watch a magnificent white heron as she fishes. We hear the little green kingfisher crackle before he swoops, deftly stealing the heron’s dinner. We’ve brought our rods to do a bit of cast fishing, but neither we nor the heron score any trophies before the heavens upend again.

The Storm

The storm continues throughout the afternoon. We make a run to the camp store for dry wood, but find it closed against our optimism that the storm will pass. After sunset the wind and rain take on a howling intensity that assures no one is venturing out. Our camp wood is soaked, our chairs have been whipped into a rising river of runoff, and now, as we try to sleep it’s apparent that our air mattress is slowly going flat. Squinting outside I feel a lame sort of pride to discover that the tablecloth I had affixed to the picnic table with pushpins is still in place — for all of another 30 minutes. Jurgen and I feel charged by the storm, but not anxious. We know we are one family out of a handful in the park, but are confident that if there is any real danger the rangers will come for us. It is a rush to be so exposed to such rollicking weather. Elliott is silently tucked away in his tent, but I can hear him rolling about. Concerned the storm has him too worried to sleep, I start to climb the ladder and check on him. I stop when he calls down. “Did you ever not want to sleep because you just want to keep doing what you’ve been doing?” Yes, I say, wondering what’s coming. The storm couldn’t have been farther from his thoughts. “I don’t want to sleep. I just want to fish and fish and fish and fish…” It becomes a mantra as he chants himself to sleep.

Jurgen and I silently high-five one another. We’ll leave early the next day without having ridden horses, rented a canoe, fished from the lighted pier or hiked the pine-shaded trail. We have lost fishing gear to fire, seen our camp chairs sail away in flash flood, and are fully prepared to spend a wakeful night taking the measure of the wind. Yet, for all its slings and arrows, the trip has been a roaring success. A fisherman has been born.

Details:

Lake Livingston State Park is 1 mile southwest of Livingston and 75 miles north of Houston. Travel from Livingston south on US Highway 59 to FM 1988. After 4 miles turn north on FM 3126 and travel 1/2 mile to the park entrance. The high season at Lake Livingston begins in March and runs through Labor Day. Campers have their choice of 170 campsites in four camping loops. Sites vary from secluded, water-only campsites to RV sites with water, electrical and sewer hookups. There are 21 “Premium” campsites lakeside in the Piney Shores campground adjacent to the 10 wheelchair accessible screened shelters.

The Pineywoods Nature Walk is a handicapped accessible 1-mile boardwalk loop through the forest and past a frog pond and hummingbird garden.

The swimming pool overlooking the lake (lake swimming is not encouraged) is open Thursday through Monday from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Trail rides from the Lake Livingston Stables can be reserved at (936) 967-5032. Breakfast and dinner rides are available. Rides are offered 5 to 6 times daily during high season and on a limited weekend schedule between Labor Day and Memorial Day.

Insect repellent is highly recommended.

Daily use fee is $3 per person. Children 12 and under get in free. Camping fees vary. The park is open daily and the office is open from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. For more information about the park call (800) 792-1112 or visit <www.tpwd.state.tx.us>. To make reservations call (512) 389-8900 or go to www.tpwd.state.tx.us/park and click on Make Park Reservations.