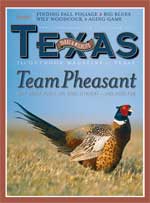

High Plains Pheasants

Since teamwork among hunters is the key to success, the more the merrier.

By Henry Chappell

Our guide, Cal Ferguson, coached us before we piled into pickups to head to our first spot. We’d be hunting a tailwater pit. The birds, if they were there, would be very spooky. No talking. No slamming doors. Keep the dogs close. Uncase the guns, hustle under the fence and load up. Spread out. Maintain a spacing of about 20 yards. Proceed on the signal. We’d be into pheasants right away or not at all. Quite a shock to this longtime bobwhite hunter accustomed to finishing off a thermos of coffee, laughing it up and sorting gear while the dogs limber up on the ranch road for 10 minutes.

A few minutes later, gun case zippers and warnings hissed at dogs were barely audible above the stiff wind. Only a few wispy clouds showed in the Panhandle sky. Ice rimmed the puddles and stock tanks. My buckskin shooting gloves held little warmth, but protected my hands from the cold receiver of my old humpbacked Browning A-5.

The seven of us followed orders precisely, but the birds weren’t there. After a five-minute walk, Chad shrugged and ordered us back to the trucks. Opening day. Plenty of birds, plenty of country, perfect weather. No worries.

Ten minutes later we spread out to drive a wide strip of weedy cover bordering a huge irrigated milo field. Brushy fencerow, sunflower stalks, lots of ragweed and sage. This quail hunter felt right at home. Sure enough, 60 yards in, I stepped into a big covey of bobwhites. No one mounted a gun. We’d forgotten to ask if we could shoot quail. Turns out that on Ferguson’s pheasant hunts, quail hunting, though certainly not required, is strongly encouraged.

Twenty yards further on, a six-point white-tailed buck leapt out of a patch of sunflower stalks. Then pheasants started flushing. Shotguns thumped amid shouts of “cock!” and “hen!” To my right, Chad Todd dropped a rooster into a stock tank. His black Lab, Scout, sent ice shards and water flying. A few steps later, I dropped a bobwhite which Scout, still wet from his swim, plucked out of the fencerow. He started toward Chad, changed his mind and headed toward me, then evidently decided the bird belonged to my host, Jason Stilwell. Chad blew his whistle and Scout sat politely holding the bird until I took it.

We continued for a quarter of a mile, flushing pheasants and quail. By the time we reached the end of the field, jaunty tail feathers poked from several game bags.

Pheasants seem as native to the High Plains as buffalo grass. Instead, they’re only as natural as corn, milo and wheat. In North America, these Asian immigrants were first stocked successfully in 1881 in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Through subsequent stocking and natural expansion, the birds moved into the farmlands of the Great Plains.

Biologists believe pheasants first emigrated from western Oklahoma to Texas in 1939 or 1940. Releases by private landowners around that time also may have helped establish small populations in several areas of the Panhandle. By 1946, the then Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission estimated the maximum population at about 1,000 birds.

Pheasant populations increased in the northern Panhandle counties during the 1950s as irrigated cropland replaced dry farming and ranching on the shortgrass prairie. Unlike quail, which thrive on native rangeland, pheasants are farmland birds dependent on cereal crops. TPWD released both captive-raised and wild-trapped pheasants into suitable habitat through the early 1970s. Also, during this period, the U.S. Soil Conservation Service provided birds to private groups for stocking. More recently, Farm Bureau members released pheasants in Swisher County. These releases expanded the birds’ range south of the Canadian River breaks, which had previously formed an impassable barrier. By 1977, pheasants inhabited parts of 33 High Plains and Northern Rolling Plains counties.

TPWD biologist Jeff Bonner of Pampa describes ideal pheasant habitat: a nice mix of tall grasses for nesting cover; weedy areas bordering fields of corn, milo or wheat; the wooly, nasty-looking bottoms of dry playas. “Find this combination, and you’ll find birds,” he says.

That certainly describes the habitat Cal Ferguson leases in Roberts and Gray counties. Unfortunately, this once-common patchwork is fast disappearing as economic factors force farmers to switch from grains to cotton. Center pivot irrigation has replaced tailwater pits, and the general trend has been toward cleaner farming. As a result, the Texas pheasant population has declined steadily over the past 20 years, though the past two years have shown a slight increase due to near-perfect rainfall patterns. Nevertheless, Texas pheasant hunters harvested around 36,000 cocks during the 2002 season.

Pheasants follow a consistent daily routine: roost, feed, loaf, roost. Hunt the best habitat in the world at the wrong time of day and you’re wasting your time. Around sunrise, the birds leave their roosts in heavy grass or weeds and fly to grain fields. After filling their crops, they head back to cover to loaf away the middle of the day. Late afternoon, they feed again, then roost. In the Panhandle, CRP fields — farmland taken out of production and planted in grass under the federal government’s Conservation Reserve Program — provide much of the best loafing and nesting cover.

High wind makes pheasants spooky. They may flush a hundred yards out of shotgun range or hold so tight you’ll nearly have to step on them. Extremely cold, nasty weather will send the birds to the heaviest available cover. According to Ferguson, the birds often congregate in roadside ditches during wet weather.

Most Texas pheasant hunts are social affairs. Unlike quail and other game birds that often hold for pointing dogs, pheasants prefer running to flying. Organized drives are the most common hunting method, with several hunters walking abreast toward blockers waiting at the far end of the field.

“Generally, with pheasant hunting, the more the merrier,” says Bonner. “Three guys out pheasant hunting are going to have a tough time getting their six birds. But if fifteen go, they’ll have a better chance of getting their 30 birds.”

If all goes according to plan, some of the birds will flush within range of the drivers and others will fly over the blockers after running the length of the field.

Of course things rarely go exactly as planned. Birds often flush out of range of the drivers and fly out the sides of the fields instead of over the blockers. Other birds sit tight while the hunters walk by, or run ahead then double back and skulk between drivers. Some let the drivers pass then flush. Or dozens of hens flush, but no cocks.

Ferguson stresses the importance of keeping the space between drivers to 25 yards or less. Obviously, the more drivers the tighter the spacing can be. Generally, it’s better to thoroughly comb an area than spread hunters too thin in an attempt to cover the entire field.

Some pheasant veterans prefer a U-shaped drive, with those on the outside slightly ahead of those in the middle so as to funnel birds into the formation of hunters. Bonner recommends zigzagging drives with occasional stops of a minute or more. Pheasants generally move with the hunters and will sometimes lose their nerve when things get quiet.

Effective drives require organization, cooperation and the utmost attention to safety. Sort out shooting rules ahead of time. Birds often flush within range of more than one hunter. Is the bird fair game for others after the nearest hunter misses once? Or does the quickest shooter get first try? Keep blockers in mind when you near the end of the drive. No one likes to be peppered with shot. Wear blaze orange. It’s far too easy to focus on that gaudy rooster and fail to see your camo-clad buddy.

Groups aren’t for everyone. Solitary hunters or a couple of buddies can take home a few birds. Forget the giant CRP fields. Think small patches of cover and overgrown fencerows. Remember, pursued pheasants want to move from lighter to heavier cover. Don’t let them. Start in the wooly stuff and force the birds toward open ground. Zigzag. Stop often. If you’re hunting with a dog, don’t just amble along behind him. Work as a team. Take advantage of natural or manmade contours — ditches, fencerows, draws — to funnel birds into tighter areas.

A pair of hunters can take turns driving and blocking, always working from heavier to lighter cover, from wide to narrow. When approaching a likely strip, the blocker should quietly hustle ahead and into position, giving the area a safe margin to avoid disturbing the birds. When you near open ground or a natural restriction, get ready.

The ideal pheasant dog quarters close, stops to the whistle, doesn’t chase flushed birds out of the country and hunts diligently for downed birds. An out-of-control dog is far worse than no dog at all. On our hunt with Ferguson, we had in addition to Chad Todd’s fine Labrador Scout, two other well-trained Labs — John Edmond’s Dixie and Greg Rowan’s Star. The dogs worked just ahead of our drives, always within shotgun range. We would’ve lost a shameful number of birds without their help.

Pheasants frustrate pointing dogs, but close, careful workers can be effective in scattered patches of cover where pheasants tend to hold. Here again, teamwork is critical. Help the dog by choosing likely areas and acting as a blocker. In general, it’s best to leave your big-running pointer at home.

Pheasants are tough. Very few hit the ground dead. Dally and you’ll probably lose your bird. “The key to recovering cripples is to get there with a dog as quick as you can,” says Ferguson. “And remember, the bird is likely to have run by the time you arrive.” Ferguson’s pheasant dog Riggs, a sharpei, pit bull, yellow black-mouth cur mix (yes, you read right), often finds pheasants a hundred yards or more from where they went down.

Pheasants call for heavy loads — at least 1 1/8 ounces of number six shot. Some old hands prefer number four shot. Most serious pheasant hunters tote a 12-gauge. Modified choke is a good all-around choice. Ferguson prefers full choke late in the season, when long shots are the norm.

Finding good pheasant hunting can be tricky if you lack local connections. Given the short season, few hunters invest in pheasant leases. Reputable outfitters and day-hunting operations are the safest bet for the average hunter. I arranged my hunt through Adventure Outdoors. Founder Jason Stilwell partners with several high-quality ranches and hunting operations such as Cal Ferguson’s 4F Outfitters, which leases some 38,000 acres for trophy deer, pronghorn, turkey, quail and pheasant hunting in the northern Panhandle. Chambers of commerce in some of the small towns in pheasant country may offer information on outfitters and day-leasing operations.

Don’t overlook public land. In the 2005-2006 season, TPWD offers pheasant hunting on about 14,257 acres through the Public Hunting Program. That’s quite a deal for the price of a $48 annual public hunting permit.

By late afternoon, we’d flushed dozens of pheasants; several members of the group had limited. Jason and I stopped along a gravel road to take photos while Cal and a few others worked some promising cover a bit farther on. We snapped our photos with the setting sun and a great swath of shortgrass prairie as background. Across the road, a bobwhite whistled. Time to covey up and head to roost. Behind us, a rooster cackled. From up the road came the sound of laughter and dog whistles. Back at the lodge, supper and a roaring fire waited. They could wait a little longer.

Details:

Panhandle Pheasant Season runs from December 3 to January 1 with a bag limit of two cocks per day. For current and complete regulations as well as information on public hunting opportunities, contact TPWD at (800) 792-1112 or visit <www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild>.

Pheasant hunts can be booked through Adventure Outdoors, (214) 336-9052. <www.livetohuntandfish.com>