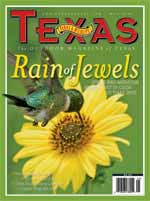

Picture This

Our chief photographer shares his insights.

The Photograph as Trophy

By Earl Nottingham

There’s no greater prize than a memory well-preserved.

“A piece of scenery snapped by a dozen tourist cameras daily is not physically impaired thereby, nor does it suffer if photographed a hundred times. The camera industry is one of the few innocuous parasites on wild nature” — Aldo Leopold

We’re all hunters. Yep, when it comes to enjoying the outdoors, we all hunt in our own way. Whether it’s biking, mountain climbing, kayaking, camping, fishing, hunting, birding, photography … you name it … we’re hunting for the reward of an enjoyable and memorable outdoor experience. And from the West Texas desert to the forests of East Texas, we have no shortage of outdoor recreational possibilities. And unique to each activity is its own version of the “trophy,” some measurable outcome of the activity that defines an ultimate success.

The concept of the trophy in outdoor recreation was poetically illustrated by Aldo Leopold in his classic book of essays, A Sand County Almanac, in which he describes trophies as “The physical objects that the outdoorsman may seek, find, capture, and carry away. In this category are wild crops such as game and fish, and the symbols or tokens of achievement such as heads, hides, photographs, and specimens.” He goes on to add that “The trophy, whether it be a bird’s egg, a mass of trout, a basket of mushrooms, the photograph of a bear, the pressed specimen of a wildflower, or a note tucked into the cairn on a mountain peak, is a certificate. It attests that its owner has been somewhere and done something.” Put another way, the trophy is a validation of the experience itself.

For the outdoor photographer, the hunt for the trophy photo can be as intense as any Hemingway safari. The planning, scouting and stalking skills are just as important with a camera as with a gun and the framed photo hanging on the wall can bring as much pride as any taxidermist’s mount. Both, as described by Leopold, are certificates in their own right, and a glance at either one will immediately bring back the experience and emotions of the day.

But there is another type of trophy photograph, one that doesn’t require the stalking of an animal or a difficult hike to a mountain summit for a magnificent sunset. Often looked down upon by photographic purists, the lowly “snapshot” probably has more of an intrinsic trophy value. While often lacking great artistic or technical merits, the off-color, faded, coffee-stained prints that overflow shoeboxes and photo albums can be considered the trophies of the heart. I often pose the question: “If your house caught on fire, what one thing would you try to retrieve (assuming everyone was out safely)?” Invariably, “family photos” is the answer, a testament to the power of photography to recall cherished memories of faces and times gone by and simple validation that we were part of life. A commentary by A. Hyatt Mayor hangs in a simple frame in my office, serving as a reminder of photography’s true trophy:

Mayor writes, “As today’s clothes obsolesce into yesterday’s costumes, old photographs become windows into a romantic past, fossil instants where life in all its trappings is struck with a catalepsy, for they can say more clearly than any painting; ‘I was there.’”