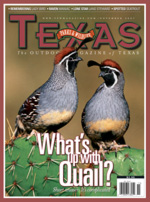

What’s Up with Quail?

Large-scale teamwork may be the only way to meet the quail’s highly specific habitat needs.

By Henry Chappell

One or two years per decade, when rain comes at the right times, in the right amounts, it’s easy to be a Texas quail hunter. Stop to open a gate and a covey flushes from the brush by the cattle guard. Spend an afternoon driving around a well-managed Rolling Plains ranch and you’ll see more quail along the roads than hunters in the South and Midwest see in a year. The bird dog and shotgun business booms. The better guides are booked up a year or more in advance.

About as often, everything conspires against quail and quail hunters. Drought hits in the fall and continues through spring and summer. The weed crop fails. Simple survival requires all of the birds’ energy, leaving none for mating and nesting. Nothing seems to thrive but grass burs and prickly pear. Fair-weather hunters turn to other game. Seasoned quail hunters get out a few times in the interest of tradition. They’ll take it easy on their dogs, enjoy the outings, shrug and wait for a better year.

But the 2006-07 season had even the most experienced hunters shaking their heads. I kept hearing, “worst year since ’84,” and “worst year ever.” Several top guides shut down in December.

It was a strange year, too, because habitat in many areas looked great. Of course there’s a good explanation. Late summer rains greened up the plains, but, for the most part, it came too late to stimulate breeding.

Still, we all wondered: Was this just another rough year to be endured, or had something changed?

There are several parts to the answer. I’ll begin on a bleak note.

Bobwhite quail are doing poorly across most of their range. According to the National Audubon Society’s 2007 report, State of the Birds, the northern bobwhite quail ranks first on the list of common birds in decline, down 82 percent since 1967 — from a population of about 31 million to 5.5 million today.

More specifically, bobwhites declined in Texas at a rate of 5.6 percent per year between 1980 and 2003 — a total loss of about 75 percent. Blue quail have declined at a rate of 2.9 percent per year over the same period for a total loss of 66 percent.

What’s going on?

“Basically, it amounts to changing land use over the past 100 years,” says Robert Perez, TPWD’s Upland Game Bird Program leader. “We’ve seen millions of acres converted to habitat types that may be fine for white-tailed deer, but not for grassland birds.”

Unlike grackles, house sparrows and starlings, which thrive in habitats ranging from farmland to fast-food parking lots, quail have very specific needs. Low, woody cover such as shinnery oak, blackberry and sumac serve as “screening” or “loafing” cover. Perennial warm-season bunch grasses provide nesting cover. Annual forbs such as ragweed, croton, sunflower and pigweed produce high-calorie seeds the birds need to make it through winter. During spring and summer, various types of insect-rich, herbaceous growth serves as brood-rearing cover. Ideally, these habitat types should be interspersed so that all the cover types are available on every acre of land. Remove just one component and the birds disappear.

According to Jason Hardin, former Audubon Texas’ Quail and Grassland Bird Initiative coordinator and now TPWD Upland Game Bird Program specialist, areas east of Interstate 35 have suffered the most serious declines. “Quail have gone extinct locally in a few spots or survive on a few isolated islands of remaining habitat. The Post Oak Savannah and Pineywoods currently support very small populations,” he says.

Ironically, East Texas once boasted some of the country’s best quail hunting. Through the 1950s, tenant farming created a patchwork of ideal bobwhite habitat. Brushy fence rows provided ideal screening cover, while weedy field edges and forest clearings kept the birds well-fed.

Over the past several decades, fire suppression has allowed brush to overrun savannahs, and modern agriculture, which favors large pastures, clean fence rows and “improved grasses,” has drastically changed the landscape. In deep East Texas, mature pines now stand where yeoman farmers once worked their mules.

So what’s the good news?

Quail are holding fairly steady in their vast strongholds on the Rolling Plains and South Texas Plains. But while quail lovers can take comfort in that fact, it only serves to highlight the seriousness of the declines in the eastern half of the state.

More troubling yet, the bobwhite is an indicator species — a “canary in the coal mine” — whose status reflects the overall health of its ecosystem. It should come as no surprise that many other grassland bird species are in trouble as well. According to the Audubon Society, eastern meadowlark and loggerhead shrike populations are down more than 70 percent. Field sparrow and grasshopper sparrow populations have suffered declines of more than 60 percent.

Any recovery strategy that benefits bobwhites will also benefit other grassland species.

In 2002, the Southeast Quail Study Group, under the auspices of the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, completed the Northern Bobwhite Conservation Initiative, a large-scale recovery plan that currently encompasses 22 states.

In order to provide specific local solutions, the strategy contains several state or “step-down” plans, including the Texas Quail Conservation Initiative, which coordinates management efforts based on best available science, policy and practices.

Organizationally, Texas’ effort consists of the Texas Quail Council, a steering committee composed of representatives from universities, non-governmental organizations, and other leaders in the scientific and conservation community. The council, which meets quarterly, makes policy recommendations to TPWD and other agencies with the ability to impact quail habitat in Texas.

The plan also includes provisions for the study and management of Texas’ other quail species: blue or scaled quail, the rare Montezuma quail and the Gambel’s quail of far southwestern Texas.

Objectives include stabilization of quail populations within the next 10 years, creation and restoration of suitable habitat for quail and other grassland birds, and education and support of landowners and public land managers.

Biologists estimate that to meet these goals, Texans must improve habitat on 40 million to 100 million acres.

Drive along back roads in the eastern half of Texas, and you’ll see pockets of quail habitat: native grasses, a mixture of herbaceous and low, woody cover, nice stands of ragweed, croton, or sunflower, and patches of open ground. You might think there’d be a covey or two around, but chances are, the bobwhite’s dawn hail call hasn’t been heard in the area for years.

That’s because you’re looking at a small island of habitat — a fragment. Quail and other grassland birds isolated on fragments are highly susceptible to predation and disease. On large, healthy tracts of good habitat, especially those connected to other tracts by viable wildlife corridors, predation has little effect on long-term populations.

“You can’t manage quail on 50 acres at a time,” says Perez. “Habitat fragmentation is one of our biggest challenges.”

Wildlife cooperatives offer part of the solution.

Although co-ops aren’t new — in Texas, the practice dates back to 1955 — they’re increasingly important as more and more large ranches and farms are broken up into smaller properties.

By forming wildlife cooperatives, property owners in a given area can work together to manage wildlife habitat on a much larger and more effective scale than is possible on a property-by-property basis.

Along with TPWD’s technical guidance biologists, Audubon Texas provides assistance to co-op members.

In 2004, a group of landowners in Colorado and Austin counties, near the Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge, founded the Wildlife Habitat Federation, a co-op that now includes some 34,000 acres. According to Hardin, bobwhite densities on some co-op properties approach a bird per acre in good years — excellent by any standard.

Landowners in Navarro County, in the Blackland Prairie Region, have formed the Western Navarro Bobwhite Restoration Initiative. Currently, the co-op has about 29,000 acres under management. With support from Audubon Texas and TPWD, the group holds landowner workshops and combines resources for habitat improvements.

Assistance isn’t limited to private lands. Hardin is especially proud of Audubon Texas’ work at Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area, where technicians cleared encroaching brush and trees to restore savannahs.

In 2006, The Conservation Fund, of Arlington, Virginia, acquired a 4,700-acre ranch in Fisher County, near Roby. The property, now called the Rolling Plains Quail Research Ranch, will be managed by a nonprofit foundation. The ranch will serve as a research and demonstration facility where biologists will deepen their understanding of bobwhite and blue quail ecology and management.

“We have several students up there already,” says Dale Rollins, the ranch director. “We’re collecting baseline data this year on small mammal and quail populations.”

Rollins, a professor and extension wildlife specialist with the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, is working with researchers at Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute to refine quail census methods. Currently, biologists estimate relative quail densities by walking transects and driving back roads. Rollins and his colleagues hope to use helicopter surveys and other methods to measure actual populations.

According to a worn-out aphorism, when it rains in Texas, it rains quail. Notwithstanding the fact that drought-prone regions of Texas hold most of the quail, it just isn’t that simple.

Drought is a natural part of plains ecology and plays a role in the boom seasons that make West and South Texas popular among quail hunters.

Much like fire, searing drought can serve as a cleansing or disturbing agent, burning away thick perennial ground vegetation that chokes out annual forbs and inhibits quail movement and foraging.

Conversely, on unmanaged land, several consecutive wet years can result in thick stands of grass and other rank growth. Quail numbers decline, then drought returns and wipes the slate clean — almost. Seeds of ragweed, croton, snakeweed and dozens of others lay hidden, waiting for rain. Likewise, beneath brittle clumps of little bluestem, grama, curly mesquite, buffalo grass, and other natives, roots lie healthy and protected.

And a few quail survive. Anyone who hunts running, wild-flushing, drought-honed survivors knows that only the fittest birds start the comeback. When an old-timer counsels a young hunter to practice restraint and “leave some seed,” he’s employing an apt metaphor.

The drought broke in 2007, and the surviving “seed” responded. Although quail populations are unlikely to go from bust to boom in a single year, there’s reason to be optimistic about the upcoming season. Research indicates a relationship called “density dependent reproduction,” which means that nesting success and brood survival are highest under conditions of excellent habitat and low population density — a perfect description of this past spring.

The birds will always do their part. It’s our job to make sure that they have the chance.

Details

- Audubon Texas (www.tx.audubon.org/Quail.html)

- Team Quail (teamquail.tamu.edu)

- Quail Unlimited (www.qu.org)

- Quail Forever (www.quailforever.org)

- Wildlife Habitat Federation (whf-texas.org)

- West Navarro Bobwhite Recover Initiative (www.navarroquail.org/index.htm)