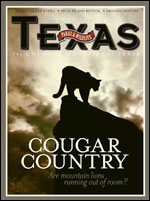

In Search of America's Lion

People are seeing more mountain lions than ever in Texas. Has their population increased or are they just running out of room?

By Wendee Holtcamp

Golden sunlight dances through the agave and sagebrush of this desert ecosystem as I catch my first glimpse. Big Bend National Park preserves a huge tract of the biggest desert in North America - the Chihuahuan - and despite its reputation for rugged desert mountain scenery and biological diversity, it remains one of the nation's largest, most remote and least visited national parks. I can't count how many people express shock that I have never visited Big Bend before, especially as a conservation and adventure-travel writer who has called Texas home for 13 years. Now I have a compelling reason to go. More people see mountain lions - also known as cougar, catamount, puma or panther - near Big Bend than any other region of Texas.

Starting from the Basin, I opt for a daylong hike up and back down 7,825-foot Emory Peak, the highest point in the Chisos Mountains. I take the Pinnacles Trail, where a sign declares: "Lion Warning. A lion has been frequenting this area, and could be aggressive to humans." If I don't spot a mountain lion, I hope at least to see some tracks on the trail or, erm, cougar poop. What can I say? We naturalist types get excited by even relict signs of elusive creatures.

Over the past few years, both sightings of mountain lions and the number killed in Texas have increased. Does this reflect an actual increase in the population? No one knows for sure.

Cougars have the most widespread distribution of any terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere, ranging from the southernmost tip of South America through Central and North America - at least historically. Cougars colonized North America at the end of the Pleistocene Era, 10,000 years ago, when many species had just gone extinct for unknown reasons - including the saber-tooth cat, woolly mammoth and giant ground sloth. When European settlers arrived, they relentlessly persecuted cougars. Eventually people eradicated the cats from the eastern United States - except for the few remaining Florida panthers, which remain an endangered subspecies. Cougars maintained a foothold throughout western North America and South America.

They evolved with deer and other native mammals as prey, but cougars also kill cattle and sheep. Although cougars sometimes prey on weak cattle, something about sheep madly dashing back and forth makes a cougar's hunting instinct go haywire; a cougar may kill a dozen or more in one fell swoop. According to Mike Bodenchuk with USDA Wildlife Services, the most sheep killed in one incident is 102. They don't cache these for later dining, or gorge on the sheep. Rather, seeing dashing sheep triggers their ambush-and-kill instinct. They really can't help themselves. Needless to say, this has not made them very popular with local ranchers.

Here in the protected 1,252-square mile national park, cougars still thrive, though they need a lot of room. A single male mountain lion defends a territory of up to 80 square miles, while females use 20 to 30 square miles. But when cougars wander beyond park boundaries, they often meet with untimely deaths. On private land, cougars are not protected in Texas and can be killed legally year-round by anyone with a valid hunting license.

Cougar sightings at Big Bend had remained fairly steady over the years, but sightings have recently decreased during summer months. Increases in black bear populations in the park may be the reason, says Big Bend National Park Service wildlife biologist Raymond Skiles. Summer coincides with heightened black bear activity (they hibernate during winter months) and they may be scaring cougars off their kills. "Lions are better hunters," says Skiles. Cougars are ambush predators, agile and fast, and can jump 20 feet horizontally, or straight up a tree. But it takes a lot of effort, energy and luck for a cougar to take down a deer, and bear scavenging may lower a cougar's reproductive success. "Bears are happy to bluff and use their size to take food. Lions are easily intimidated." Skiles emphasizes that these are his impressions without hard science behind them, but based on 20 years of working with mountain lions.

Under Skiles' guidance, Big Bend National Park runs a program tracking cougar sightings and trends over the years, offers interpretive programs, and responds to any incidents that may occur. While they define sightings as any view of a cougar near or far, it escalates to an "incident" when a cougar in close range does not move away, approaches or follows a person. They have around 160 to 180 sightings per year, but only 19 incidents have occurred in the past 10 years, most of which ended without further concern. The park has had five attacks with injury in the past 25 years, and none of the attacks was fatal to humans. "They are carnivores, and at the same time we have a responsibility to the safety of visitors," explains Skiles. "If there's an incident, some places might call in dogs and take it out. Others might say this is a wilderness and there are inherent risks. We act upon risks that are significant, but without creating Disneyland." He explains that most attacks occur where mountain lions have grown up around human visitors, and attacks are extraordinarily rare in remote areas.

The trail winds steeply upwards to where I need to boulder up to reach the final summit. I'm a bit disappointed that I haven't seen a single track or scat, not to mention a cougar. I head back down the Pinnacles Trail to complete the loop. Halfway down, I spot something in the mud. "Look!" I say to my friend. "Tracks!" Sure enough, some smudges that could be anything - dog, cougar, bobcat. A few minutes down the trail, another muddy spot has clear tracks with telltale signs - no claws, and a three-lobed heel. But the best find? A large hair-filled cougar poop.

Most of what scientists know about Texas cougars comes from a few studies in the late 1980s and 1990s, which involved monitoring where the cats wandered, but a recent genetic study has shed some new light on the situation. TPWD biologist John Young worked with Jan Janecka at Texas A&M's Vet School and Michael Tewes of the Feline Research program at Texas A&M-Kingsville, and colleagues took genetic samples from cougars killed by ranchers or by USDA Wildlife Services. Their research revealed two populations of cougars in Texas, which - for the most part - do not intermingle. One exists in South Texas, and another in West Texas, including Big Bend National Park.

"What Jan's study showed is that Mexico is likely our source for the South Texas population," says Louis Harveson, a Sul Ross University professor who has studied mountain lions in Texas since his doctoral work radio-collaring them in the 1990s. In scientific terms, a "source" is a region that provides a net surplus of animals, whereas a "sink" is the opposite. Sources and sinks are determined by habitat quality, which includes not only prey abundance but also hunting pressures.

One would think that large protected parks and preserves would serve as sources, but in five studies conducted between 1986 and 1997, cougars suffered high mortality, especially as they moved off the study site. Between 50 percent and 89 percent of the radio-collared cougars died during the two- to four-year research projects, mostly due to hunting or trapping efforts by ranchers or Wildlife Services. In Harveson's study, of the 19 they monitored, about half died during the study, with five killed by deer hunters on the million-acre study site on privately owned lands.

"I'm not totally sure if you could say that West Texas is a sink," says Janecka. "Big Bend Ranch State Park could be a source, but mortality rates on surrounding private lands are pretty high, creating sinks. It's really hard to say. But I think state parks are generally too small to encompass an entire population of mountain lions."

Ranching remains a predominant land use in West Texas, but times are changing. Texas still leads the nation in mohair production, but sheep and goat ranching has declined and there's a trend toward absentee ranch owners. Whether people depend on their ranch for their sole livelihood or make their money elsewhere strongly affects attitudes toward predatory mountain lions. Not all ranch owners dislike cougars, and some go out of their way to ensure that they have quality habitat for them. One thing is certain: because so much mountain lion habitat remains privately owned, a delicate balance must be reached between these wild predators and landowners.

Although TPWD oversees the management and conservation of Texas' natural resources and wildlife, many species clamor for attention, funds and resources, and cougars as a species are not imminently threatened. However, the comprehensive statewide Wildlife Action Plan, created by many different stakeholders, lists mountain lions as a medium-priority species in Texas. The plan outlined five management needs for the species: develop landowner incentives to work on maintaining a stable population; inform people of the role of mountain lions through education and outreach; develop a statewide management plan; develop a better method for recording hunter/trapper take; and review regulatory status. Some biologists would like to see these actions implemented, but new studies may be needed to reveal a more accurate picture of the cougar's current status across the state. Mortality data may not be enough. Skiles, for one, is working on getting funding to do some of Big Bend National Park's first cougar studies in nearly 20 years.

The desire to see mountain lions took me on a heart-thumping, sweaty hike up and back down a gorgeous Big Bend desert mountain. I didn't see one, but it's still a thrill to hike through cougar country. "Lots of people come here because it's a great place to see mountain lions," says Skiles.

I may seem unusual in seeking out mountain lions, but I'm not alone. "People love the idea of mountain lions," says TPWD biologist John Young, "Until they see one close to home, and then they're deathly afraid. They're worried about their pets, their kids, themselves." Although attacks on humans occur very rarely, humans are not on the menu, or we would literally see dozens or hundreds being killed across the nation daily - we're not exactly tough prey. "There's a perception that mountain lions kill a lot of people. They do occasionally attack people, but that's really, really rare," says Young. If a mountain lion had been recently spotted in an area, he says, "Not jogging at dusk is all I'd really change of my behavior."

I'm not quite sure how I'd react if I saw one up close in the wild, gazing with its piercing green eyes, but I'd probably be thrilled. So long as it stayed a good distance away, that is. Cougars have persisted in places where persecution has led other predators, including wolves, to extinction, but they're not invulnerable. Ensuring they survive and thrive truly benefits everyone.