The Lost Art of Hunting

What we call hunting today would not be recognizable to our ancestors.

By Wyman Meinzer

Hugging the Marlin 336T tightly under my coat, I stood beneath the soaked canopy of a chinaberry tree and waited for the next rain squall moving in from the north. The incessant drip from other shrubs such as lote, mesquite and chittum had almost soaked through to my long johns, and I needed a respite from the weather to dry out and rethink my strategy for the evening.

It was deer season in the Texas rolling plains and a norther had collided with a tropical depression over our region. Conditions for hunting were optimum, as the grass, saturated with moisture, provided a quiet cushion for walking and the wet soil exposed the tracks of whitetails on the move. The day was great for an old-fashioned still hunt. I wanted to continue through the evening hour, but the rain was unrelenting, chipping away at my will to go on much longer.

Cold and looking for a dry place for some relief, I recalled a suggestion from my dad, an old-time cowboy who managed the ranch where I was hunting.

"If there is a chance you will encounter cold rain when out in the brush, take along some matches and find a rat midden," he said. "In its interior you will find dry vegetative fodder surrounding the rat's living quarters, so kick the nest apart and start a fire as the den will burn hot and you can easily warm yourself." This I did, and in short order was dry enough to continue the afternoon's hunt.

Whether it is knowing how to ignite rat middens on a soggy winter day, recognizing optimum locations for finding potable drinking water, or understanding the natural history of the quarry that you seek, it is disturbingly true that fewer and fewer people are learning these once-essential outdoor skills. In this age of spacious and comfortably furnished elevated blinds, solar-powered feeders spraying their offering of golden delight at predictable intervals or video cameras offering the "hunter" a tantalizing array of super bucks for the taking at exorbitant prices, few incentives exist today to encourage our youth to hunt in a more traditional way.

That soggy day on the Texas plains occurred more than 43 years ago, when I was a boy of 14, full of youthful energy and an ambition to excel in the old-time art of still hunting. How many miles were traversed through those sandhills along the Brazos River in search of a whitetail buck – a buck of any size – I will never know. But in those miles and days afoot, lessons in basic woodsmanship were learned that subsequently helped shape my career and my life as a whole.

I recall, some 30 years ago, my first real introduction to Texas "deer country" when Al Brothers, a wonderful friend (and co-author of the landmark book Producing Quality Whitetails), invited me to one of the H.B. Zachary ranches in Jim Hogg County to photograph white-tailed deer. I was a fledgling photographer at the time and was excited at the prospect of experiencing the famed South Texas brush country and the photo ops that it might offer. This was a time before timed feeders and high blinds were in vogue. Along the 500-mile drive from my home in Knox County, I saw only a scattering of the strange-looking elevated "box houses" and few, if any, of those 55-gallon drums on stilts that saturate the landscape today.

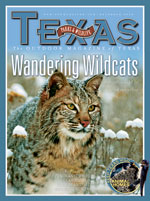

Al informed me that they didn't feed the deer, but allowed wildlife to prosper from existing browse growing naturally on the range. In other words: "You are going to have to hunt down and photograph these wild bucks without the aid of artificial feeding stations." This wasn't a problem, as I was engaged in professional predator hunting in those years, virtually living in the brush with a rifle and running 100-mile trap lines for coyotes and bobcats on several ranches in the rolling plains.

In the ensuing years that I spent photographing on the property managed by Al Brothers, I used every outdoor skill that I had ever developed as a youngster, including tracking, stalking and lying in wait along deer trails in natural stick blinds. It was tough, grueling work, but in the end there was personal satisfaction in knowing that in the process I enhanced my hunting skills while obtaining the photos needed for the assignment.

Some say it's an eccentricity and others say it's just weird that I still like to do some things the old-fashioned way. About 25 years ago I began studying the history of those last years of unfettered hunting on the Texas plains, a period that began in the mid-1870s and ended rather abruptly with the extirpation of the bison from Texas in 1879. Having been raised on a ranch in Knox County, I was interested in finding out how much hunting activity went on in this region, as well as the style of hunting practiced in the late 19th century.

After reading the original works of men who frequented the plains in those years before pioneer settlement, it became quite obvious to me that today the basic outdoor skills are so far diluted, even from the skills known a generation ago, that about the only comparison that can be made is that rifles and shotguns still go "boom" when the triggers are pulled.

In the early years, hunters took great pride in understanding the nuances of nature, such as weather-related behavioral changes in wildlife, identifying tracks and acquiring in-depth knowledge of the natural history of species indigenous to their respective region.

Disgusted by the demise of outdoor skills in our youth, and in most adults today, I immediately began teaching my own young boys, to the best of my abilities.

"Trailing is the art of evolving trail from sign," writes Colonel Richard Irving Dodge in 33 Years Among our Wild Indians, published in the late 1800s. The sobering sentence that caught my attention, however, was his comparison of the skills of white trackers to those of the Native Americans. "In over thirty-two years experience I have never yet seen one (white man) who was better than a mere schoolboy, when compared with Indian trailers."

With this passage in mind I immediately headed into the badlands north of our home in Benjamin with my two young sons (8 and 10) and started them on a lesson in tracking, realizing how terribly diluted my own skills had become. Taking a head start of several minutes and crossing hill and arroyo, I would leave enough sign for the youngsters to stay encouraged at their progress and then lie in wait on a high point for them to find me. From my vantage point I could watch their every move and engage them later regarding apparent problems they had encountered along the way. Whether they will ever need to apply the lessons learned on those excursions remains to be seen, but at least they understand the dynamics involved in this all-but-forgotten art.

With the vast majority of our youth today growing up in a suburban environment, opportunities for quality outdoor experiences are limited. Although state parks and other public spaces offer valuable opportunities for hiking and basic lessons in outdoor lore, they don't offer many of the "old school" experiences my sons enjoyed.

Some of my fondest memories are of camping in the badlands with my sons, cooking hamburgers over an open fire, listening to the sounds of the night and telling stories about the Texas of yesteryear. If our hunts resulted in harvested game, we counted ourselves fortunate, but that didn't really matter much. The experience of being a part of the land for a day or two was reason enough for celebration.

Unfortunately, with today's fast-paced lifestyle, few adults take the time to learn, or teach, the full range of hunting traditions. The next generation of hunters deserves the same rich experiences our forebears enjoyed when utilizing their skills and knowledge out in the field.

In my youth, a few decades ago, the first signs of autumn were unmistakable. Cooler nights and a noticeable change in the movement of wildlife were predictable indicators. Frequent sightings of coyotes, the result of what is termed the fall shuffle, were noted. The call of the sandhill crane rode the winds of October and the first flights of teal whistled out of the clear autumn sky. These were visual signs that I recognized from actually being a physical observer of those migrations and fall shuffles.

I now have two grandchildren, and I hope to offer them the same kind of rich outdoor experiences I enjoyed with my sons. Throughout this learning process, we will celebrate our natural and historical heritage and honor the men and women whose tracking abilities, hunting skills and keen understanding of the natural world helped define what it means to be a Texan.