Prairies and Pines

Destination: Graham

By Barbara Rodriguez

Travel time from:

- Austin - 4.5 hours /

- Brownsville - 9.75 hours /

- Dallas - 2.25 hours /

- El Paso - 8 hours /

- Houston - 5.75 hours /

- San Antonio - 5.25 hours

- Lubbock - 4 hours

North Texas trail leads to painted birds, dumplings, dead outlaws and one huge oak tree.

Just over an hour northwest of Fort Worth, the Texas Prairies and Pineywoods Trail buckles up into mesas with long-view bragging rights to big oil, big cattle and big history. It is a landscape that witnessed the cowboy and Indian dramas celebrated in Technicolor classics like The Sons of Katie Elder and The Searchers, the blazing of the Goodnight-Loving partnership and trail, the birth of the Cattle Raisers Association, wagon raids, jail breaks, massacres and more than one trail of tears. The vistas that sweep from the high buttes to muddy bows in the Brazos have been sporadically broken by the boom and bust of oil towns. But since 1871 the town of Graham, with its gigantic square and broad-shouldered pride, has shored up a county population once decimated by the Civil War. History aside, our family weekend was about the birds and the trees (at least one whopping big 'un) and all the steak we could eat - and, of course, the movies.

Day One

We pack boots and lawn chairs - essential gear for a stay that promises to include a one-two punch of firsts for my husband and son: horseback riding and a drive-in movie.

Scarcely underway, we pull in at Weatherford's Downtown Cafe, where a good year for peaches means a very good chance at cobbler. The mural featuring cattle brands makes a nice introduction to the drover's landscape ahead (Oliver Loving is buried in the Weatherford cemetery), but the cobbler, alas, is sold out. We settle for chicken and dumplings then head for the roller coaster hills outside Mineral Wells and the Boudreau Herb Farm. The Herb Lady, as Jo Anne Boudreau's radio persona is known, proves to be the Texas answer to Professor Sprout - she's colorful, knowledgeable and, like Harry Potter's botany teacher, somehow magical.

The farm store overflows with dried local herbs as well as exotic imports. And while hand-penned signs promise that "counseling" will cost you $100 per hour, throughout our visit she dishes out gardening tips and herbal remedies freely. We leave with a bottle of comfrey oil liniment labeled: "For the cowboy, his horse, his dog and his cows." That's what I call all-purpose.

In a blink we are at the gates of the Wildcatter Ranch, the spectacularly situated guest ranch - long on history and views (with a much-lauded steakhouse) - that is to be our headquarters. Rocking chairs and hammocks, horseshoes and tetherballs might win some guests' hearts, but the minute he spots the staccato sign reading "Danger Rocks Snakes," my son Elliott is quite sure we've crossed the great divide into boy heaven. The saltwater pool that seems to pour over the horizon cinches the deal. "My life is complete," he sighs. We settle into the Butterfield Stage room - each room tells a local story through photos and paintings of boomtowns, Indian chiefs, wildlife and in our case stagecoach lore (our mile-high beds are fashioned from wagons, complete with wheels). Toss in dozens of suede pillows and a gas log fire and the comfort factor is light years beyond that awarded early stage passengers.

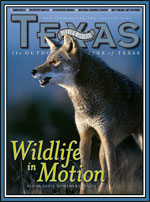

Before splashing into the pool we check out the ranch "scavenger hunt," a set of laminated sheets assigning points to sightings of featured wildlife and flora. We play at this game all weekend, starting with my husband Jurgen's whoop of glee at spotting a roadrunner in full strut.

After a few minutes of roping practice on stubbornly elusive hay bales with horns we head for the river, scraping along a road that makes Jurgen (who for some mad reason has had his car detailed for the trip) cringe. After weeks of record-setting rain, the red scales of mud along the Brazos look deceptively solid. Within minutes, much to his father's dismay, Elliott is knee deep in muck. I join him in a slip-sliding exploration of the banks, trying to disguise the fact that in the chase of a dragonfly I have lost a shoe to the sucking mire. Much German engineering goes into the scraping of shoes before the boy and I are banished to the car's far back.

On what might have been a sullen ride to our room, the sudden sighting of not one but two painted buntings has us all yodeling "Woohoo!" In years of birding I'd seen only one feathered rainbow before; to see two on the same day, in the same minute, is a treasure. Muddy shoes and all, we're comrades again and even the turkey buzzard lording over a rusty oil tank seems party to our joy.

Once we've cleaned up, we belly up to the Wildcatter Steakhouse for a dinner of Bob Bratcher's hand-cut, best-steaks-ever - including a plate-lapping 2-pound porterhouse - that makes Jurgen the happiest carnivore alive and Elliott too catatonic for apple strudel. Cook Bob's food is served up in manly-man portions that promise the kind of leftovers that are fought over in midnight raids.

As evening unspools, we sit on the porch, listening to the wind murmuring the news of the gloaming, as it has for hundreds of years in war and peace. Soon our snores are less gentle than the wind.

Day Two

A rosy day dawns to the cascading calls of whippoorwills and canyon wrens, but the first point-scoring sighting of the day is my rufous-sided towhee. Snagging a trio of the mountain bikes available to guests, we ride to the ranch house for breakfast before mounting up for a 90-minute trail ride my husband and son have begun to dread. I don't understand how guys who will hurl themselves down a 180-degree rock ledge on two wheels fear straddling something with four stout legs and an instinct for self-preservation. Thankfully their confidence is restored by the trail boss, a lover of lolling cow dogs and sturdy quarter horses, who takes his time in sizing us up before assigning us each a horse.

My Ted is easy to manage, if tender-mouthed and slightly dazed by the amount of clover he is to be denied on this ride. Jurgen's fears are quickly quelled by the surefootedness of his paint, Buddy - as sweet and plodding as he is enormous. Slightly skittish on the sleek but stubborn Lignite, Elliott complains at his lack of control. "I think there's something wrong with the reins." He squawks when a downhill pitch shifts him dramatically in the saddle. Jurgen saves the day by reminding him to distribute his weight as he would on his mountain bike. By trail's end we all feel far more accomplished than we are. Then Elliott asks a question I'd never before considered: "Why do horses have to stop to pee but not to poop?"

After a side trip for ribs at the Dairy Land Drive Inn in Jacksboro (I love that they serve damp washcloths with the barbeque), we make a fruitless search for the graves of the ill-fated Marlow brothers (recast as the sons of Katie Elder in the John Wayne classic) before heading to Fort Belknap. Built in 1851 as one of eight frontier forts along the Texas Forts Trail, Belknap guarded the Butterfield Overland mail route. Before the fort was abandoned in 1867, the Army spent its spare time killing buffalo, a sanctioned approach to driving the Kiowa onto reservations. In 1866, the first Goodnight-Loving cattle drive thundered forth from here, pounding out a trail that would move more than 5 million cattle, supplant the Chisholm and inspire Lonesome Dove. Today the grounds make a great place for a picnic. A small museum's eccentric collection includes old spellers, civil war bullets, long rifles and peace pipes. A brontosaurus tooth gains Elliott's favor, but for me the trip is all about the truly spectacular grape arbor, so dense and dark the temperature drops noticeably within the cavernous cover of vines.

Back in Graham, we walk the expansive town square - the nation's largest - around the 1932 Young County Courthouse and check out the Depression-era oil boom murals on the Old Post Office Museum and Art Center. A Second Street mural honors the Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, begun in 1877 to combat rustling. On Oak Street, don't miss a visit with the fabulous owner of Frances' Fabrics, still stitching up the satin pillow cases Grandma used to keep her beehive smooth.

When the sun sets it's time to queue up on the shoulder of the Old Jacksboro Highway for the Graham Drive-In, one of few left in the state. It's no night for spreading out in lawn chairs - lightning flashes and driving rain compete with the big screen - but the guys are thrilled by the retro-craziness of the crackling speaker and ranks of steamy car windows.

Day Three

We sleep in, bolt for breakfast on our bikes and ready ourselves to stalk a tree - the largest live oak in America, to be exact. But first we're to visit the Hockaday Ranch, where Kent and Nancy Pettus rent the comfortable, isolated ranch house to guests. Kent, who owns a car dealership, picks us up in a classic red convertible Eldorado that begs a stretch of longhorns across the grill. Invited to drive, Jurgen, who harbors a secret ambition to own such a "yank tank," transforms into the James Dean of Giant - give or take 5 inches and 100 pounds.

One hundred and fifty years ago the 1,000-acre Hockaday was part of the Brazos Indian Reservation, and despite the oil pumps now bucking across the horizons, it's easy to imagine little about the juniper-oak woodlands has changed. A history buff and witness to three local petrochemical booms, Pettus spins loosely linked stories of mineral rights, natural history and local legends with charming aplomb. The homey comfort of the Hockaday is antithetical to the well-padded indulgences of the Wildcatter, but its appeal, not the least of which is a splendid view, is genuine. To slouch high above a double bend of the Brazos in a lonely cliffhanging metal chair is to gain privilege to a solitary musing that is hard won these days. In addition to sloth, guests are encouraged to bump around the acreage, birdwatch and fish for bass and panfish in a 50-year-old tank.

At the end of our visit, Pettus escorts us off the ranch and to the resting place of the Marlow brothers (whether they were truly outlaws or merely ne'er-do-wells remains in hot debate). As it turns out, the elusive Finis Cemetery was established by his great-grandfather. The original Marlow marker, hidden beneath a laurel and washed almost smooth by time, is not nearly as poignant as the sentiment captured on a nearby pre-Civil War marker: "She hath done whatever she could."

But now, like the White Rabbit, we're late, we're late and we've kept the blue-eyed and passionate Jay Burkett waiting far too long. A scrapbook thick as a phone book under his arm, Burkett has cut short a family reunion to tell us the best tale of our visit: how one man dedicated himself to winning honor for a tree long denied its due. From the day he first saw the tree sprawling above a cow pasture on the Atwood Ranch, its limbs splayed with age, Burkett knew the live oak to be a giant among, well, live oaks. The tree was long known by locals to be a monster, but while rancher Jack Atwood lived he'd broach no strangers ogling it. When Jack died, Marie Atwood at last gave Burkett full access to the tree, and that was when, as he says, "I got after it."

Burkett made countless phone calls to the Texas forestry office in Abilene suggesting someone should come and see this tree. The calls were met by incredulity. As he recalls, the attitude was that if there were a giant tree in Young County, someone would already know about it. The tenacious Burkett didn't give up. He made phone calls until at last a new forestry employee, happy for an excuse to learn more about his territory, agreed one icy-cold day to drive over for a look-see. It was a whim that cost him some sleet in the teeth as his measurements proved (and three full revolutions of the tree just to be sure) that Jay Burkett was right. Several official measurements later, it was confirmed. At a height of 48 feet and a circumference of 357 inches, the Atwood Ranch tree was deemed the largest Texas live oak, a title officially bestowed in 2002. The tree officially became the National Champion two years later.

Everything about the tree seems extra large, from the bower of ivy that drapes it to the monumental splotches of cow pies that act as its first line of defense. In the droning heat, time seems to stand still as we stare up at the arthritic limbs and try to imagine what this tree might have seen in its estimated 500 to 750 years of life. No longer elegant, split and deformed by its own weight, it is more reminiscent of a dinosaur's appendage than a tree.

And yet it commands the respect it has now been given, thanks to Jay Burkett. And it confirms that if everything is bigger in Texas, it's bigger yet in Young County. As a matter of fact, in addition to the champion live oak, three other Atwood Ranch trees were found to be larger than the Uvalde County tree formerly awarded the title.

We leave the county in the hero light that makes everything better, flowers glowing, the temperature perfect. Sad to leave the birds and the trees behind, we all agree that we carry one part of the landscape home with us and make a pact to go out later and look at the stars.

Details:

- Boudreau Herb Farm (940-325-8674)

- Graham Chamber of Commerce (800-256-4844, www.grahamtxchamber.com)

- Graham Convention & Visitors Bureau (www.grahamtexas.net/cvb)

- Hockaday Ranch Guesthouse (940-549-0087, www.grahamguests.com)

- Wildcatter Ranch (940-549-3500, 888-462-9277, www.wildcatterranch.com, www.wildcattersteakhouse.com)

- Old Post Office Museum and Art Center (940-549-1470, www.opomac.org)

- Fort Belknap (940-846-3222)

- National Live Oak Tree Champion, Atwood Ranch, by appointment only. (940-549- 6510)

- Graham Drive-In, first-run movies Friday, Saturday and Sunday evenings during the summer months (940-549-8478)

- Dairyland Drive Inn (940-567-3705)