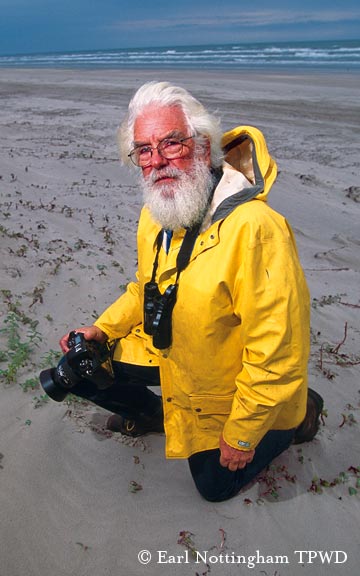

The Old Man and the Beach

When he’s not counting and cataloging birds, turtles and other wildlife, Tony Amos stays busy by saving their lives.By Rusty Middleton

Not much deters Tony Amos from his ongoing survey of the beach at Port Aransas. Not the high tides and storm surges that have, at times, floated his vehicle and then stranded him, or the violent thunderstorms and lightning that have pinned him down in the cab of his truck.

He has endured innumerable days of blistering heat in the summer, and razor sharp cold winds in winter that blast his eyes with flying sand. Not even the tens of thousands of beer-swilling college students at spring break stop him.

With his flowing white hair and beard, he cuts a striking figure, navigating his surveyor’s wheel through the chaos of parked cars, volleyballs and sunbathers to measure the width of the beach. Using a specially adapted 1984 vintage HP computer, he records the temperature of the ocean and counts the birds and other beach phenomena every other day as he has, almost continuously, for the last 30 years.

Amos’ passion for counting, sorting, cataloging and analyzing things isn’t confined to birds and water. Over the years he has added increasing levels of complexity to his survey. What began with simple bird tallies, now includes estimates of seaweed, measurements of the tide lines, numbers of jellyfish, trash of several types, cars, people, dogs, helicopters, even the messages he often finds scrawled in the sand.

Patrolling the beach at dawn, he has inadvertently encountered embarrassed people engaged in, shall we say, compromising behavior. He has found and replied to numerous messages in bottles, and once, while patrolling on a different, more remote beach, he found a dead kayaker.

In fact, pretty much everything on the beach gets observed and accounted for, including the condition and extent of the sand itself. Funded almost entirely by himself, his survey has become a remarkably detailed social and natural history document of life on Coastal Bend beaches. On paper, it fills over 300 thick, cross-referenced journals. It has already been a resource for state agencies, scientists and students. Amos thinks it will be “useful in various ways for a long time to come.”

“I wanted to see birds when I came to Port Aransas (in 1978), so I started patrolling the beach and counting them,” he says. “Over the years I just got a little carried away and started adding more and more categories of everything I saw.”

Though very little of the total beach picture escapes his eye, his particular passion is individual and banded birds. Every spring and fall, he seeks them out like an alumnus looking up old friends at a reunion.

Endangered piping plovers, for example, will always get his undivided attention. “There are only an estimated 6,000 of them left. I will see some birds back at the same small section of beach year after year,” said Amos.

A recent master’s thesis based on Amos’ survey looked at trends in bird populations and found declines in 10 of the 28 species studied and only three on the increase. In three of the declining species, a connection was seen between rising temperature associated with climate change and later arrivals in fall and earlier departures in spring.

With all that surveying, the resulting data entry, cataloging and analysis, you’d think Amos would have time for little else. At 71 he’s retired now, but for many years his beach survey was just a sideline to his full-time work as a physical oceanographer for the University of Texas Marine Science Institute at Port Aransas. In fact the only breaks in the routine came when he would spend weeks at sea in places like the South Atlantic Ocean and near Antarctica.

In the late ’60s, he started out as a marine technician operating the measuring equipment aboard research vessels. On a trip to the Indian Ocean, his intellect and extreme thoroughness got him noticed by the chief scientist when Amos and the rest of the team discovered a then-unknown current boundary where large amounts of marine debris collected. The scientist encouraged Amos to write a paper on the phenomenon, and thus began Amos’ own career as a scientist and physical oceanographer.

Amos eventually became the lead investigator on many research voyages around the world and, closer to home, participated in some of the first oceanographic science on Texas barrier islands. Amos’ work discovered the dead zone, an area of periodically lifeless water in Corpus Christi Bay. He was among the first to chart estuary currents along the central Texas coast.

Amos is a member of many professional organizations and one of the authors of a recently released study of the worldwide problem of marine debris. He has a long list of professional awards, and his list of professional writings runs an incredible 10 pages. Amos’ curriculum vitae would be the envy of any self-respecting Ph.D. level scientist or university professor. Yet he does not have a doctorate of anything, except maybe determination and focus.

Despite a long and distinguished career in academia, he has no degree at all. Amos dropped out of school at 17 and has never even attended college.

Amos’ beach survey is well known among state and federal biologists and various advocates and students of Texas beaches. His work as an oceanographer is widely acknowledged and recognized in scientific circles. Yet his real fame, at least to the general public, comes from an activity only partly related to either of those long-term pursuits. Along the Coastal Bend, Amos is the go-to-guy for sick or injured animals.

Somehow, amid all his other activities, he found the time and energy to establish Animal Rehabilitation Keep in the early 1980s. Starting with the most primitive of equipment, the ARK has grown over the years to a staff of four part-timers and about 15 volunteers.

Situated in several buildings on the UTMSI campus in Port Aransas, the ARK is the last chance for about 800 sick and injured animals per year. Mostly they are waterbirds and sea turtles, but nothing gets turned away.

Here life-and-death situations seem to occur on an almost daily basis. For example, on a November morning in 2008, someone brought in a very strong and very terrified raccoon with its head in a plastic jug. Once they managed to get the jug off, it took Amos and three co-workers to physically contain the animal, check it out for problems and then get it into a cage for later release. Fortunately, nobody got hurt, including the raccoon. “We were all trembling from the exertion and tension afterwards,” said Amos.

A tour of the facility is an education in how close encounters between animals and human activities frequently turn out very badly for the animals. Most numerous among the convalescing waterbirds are the brown pelicans. Their numbers were greatly reduced along the Texas coast, but brown pelicans are one species coming back in a major way. Their numbers are still increasing.

“At one point, I didn’t see any for a couple of years, and now I spot as many as many as 1,500 in a day,” said Amos.

For brown pelicans and many other animals doing time in the ARK, it’s all about entanglements and collisions. Pelicans can get entangled when they dive and when they get too close to fishing gear on docks and jetties. All too often that means lines around their necks or feet. When that happens, they panic and fly off and then either slowly starve or crash into things. Either way, if they are lucky, someone will see them and call Tony Amos. If he can, he will catch the victim and start the familiar process of treatment and recovery.

The other most frequent residents are sea turtles, and there are lots of them. The day after the battle with the raccoon, a loggerhead came in to the ARK, after it was found floating listlessly in the water. Nobody knew what was wrong with it, so it joined many others in the large tanks at ARK.

All the turtles at ARK are in various states of recovery or observation. Some have collided with boats; one got wedged into rocks on a jetty. Another, a green turtle, went through the hopper of a dredge. About 40 percent of the turtles that make it to the ARK don’t survive. And that’s not just a tragedy for the turtles, it is also a paperwork nightmare for Amos and his staff because all of the seven species of sea turtles found in the Gulf of Mexico are listed as threatened or endangered. These fatalities have to be documented and reported to the proper government agencies.

“One of my biggest jobs at ARK is doing paperwork and maintaining my permits,” says Amos. “To handle and rescue these animals, I have to be permitted by TPWD. I need endangered species permits from the feds, special scientific permits, an education permit, even a permit from the DEA.”

Those permit requirements and the pressing need to maintain a barebones $100,000 per year budget is what worries him about the ARK’s future. Amos is getting older and he knows there may not be someone else willing or able to take on the budget and permit requirements which demand extensive, time-consuming paperwork and training. Amos takes no salary for his work at ARK.

“I really don’t know what will happen when it comes time for me to quit,” he says with a rare frown.

Amos might worry about the future of the ARK, but he has no trouble enjoying its present, even after so much work and so many years. The end of a long day took him north of Rockport to Goose Island State Park at dusk. There, he was to release a great horned owl back into the habitat where it was found injured.

Amos put on welders gloves and slowly opened the cage while the owl fluffed up its feathers in a rage. Very carefully Amos got his fingers around its feet, drew it out of the cage, admired it for a few seconds like a work of art, and suddenly turned it loose. It flew fast and strong into a nearby line of trees and disappeared into the darkness. The only thing left glowing that evening was the huge smile on Tony Amos’ face.