Little Known and Almost Gone

The imperiled species that aren't cute or cuddly face an uphill battle for survival.

By E. Dan Klepper

The epithet "South Texas ambrosia" suggests something more than just a nondescript member of the aster family that once thrived in the state's southern veldts and open savannahs. It also denotes a special place in the hearts of many Texans, including this writer who spent a childhood wandering the South Texas plains shooting rabbits and swimming away the summers in stock tanks. Each phase of life - from toddler to teen and on to adulthood - played counterpart to the simmering heat or harsh blue northers of the state's southern reaches.

The core of our family bonding took place while walking the field rows flushing white-winged doves or casting lures across stumps and riffles; we celebrated the subtle change of seasons in South Texas with trotline-caught catfish, turkey hunts, mistletoe collecting and mesquite bonfires. Over the years, good times like these have become the mind's ambrosia, a word that is derived from the Greek prefix a- for "not" and mbrotos, meaning "mortal," thus conferring an immortality upon the past. Memories, naturally, maintain their power over the course of a lifetime and a scent, a certain light, or the sound of a name like "South Texas ambrosia" can trigger the senses to draw even the farthest of moments close once again. But the plant itself, Ambrosia cheiranthifolia, has not fared quite as well despite the elixir affixed to its name. In fact, over the last 50 years South Texas ambrosia has become one of the most endangered plants in the country. The loss of its habitat has allowed the encroachment of more common, aggressive and non-native species, leaving little opportunity for the ambrosia to survive. It's as if the trigger for a fond memory is heading toward extinction, thus endangering the memory itself while something unremarkable and mundane attempts to reside in its place.

South Texas ambrosia is not the only uniquely regional feature at risk. The Texas horned lizard and the indigo snake have joined its ranks as endangered and threatened species. In fact South Texas - once vast, open grasslands with woodland valleys but now a mix of brush, farmland and savannah remnants - constitutes just one of many eco-regions in the state that harbor species in dangerous decline. The number of state species on the list to date, including mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and insects, exceeds 150 and the total continues to rise. This is an alarming count of living organisms threatened with statewide extinction, particularly in light of the fact that they are among the species that help make the Texas natural world unique.

Extinction is a troubling concept to grapple with for Texans who don't experience the influence of nature in their daily lives. Most Texans reside in urban or suburban communities where the laws of humankind prevail and nature has been relegated to lawns and gardens. Arguing against extinction is made more difficult by evidence uncovered through evolutionary biology that indicates significant extinction events have occurred due to natural causes throughout the earth's prehistory. But, unlike our ancient past, the direct cause of threatened and endangered species today is clear and unimpeachable - the loss of habitat and the degradation of healthy environmental conditions brought on by humankind. But what are the true ramifications for the decline and loss of a species and how do we - Texans who celebrate our state with record breaking white-tailed bucks, pro-caliber bass fishing, and world class birding - mount a responsible, effective campaign to end our natural world's demise?

Perhaps first and foremost we should recognize just exactly what we have in hand and what we are in danger of losing. Texas ranks second in the nation for overall diversity of species and third in the number of species unique to the state. Tragically, these statistics are followed with a rank of fourth in the number of extinct species, suggesting that the more we have the more we have to lose. Texas has nearly 630 species of birds, more than any other state in the country. One hundred twenty-six of the state's 1,245 vertebrate species can be found only in Texas and nowhere else on the planet. An astounding number of insects, estimated at 30,000, reside in Texas. So how do we pinpoint, analyze and monitor the components of our state's precious natural world and then proceed to bring their habitats and populations back from the edge?

The answer may lie in the Texas Wildlife Action Plan, an aggressive comprehensive wildlife conservation strategy launched by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department that identifies conservation priorities for the state's eco-regions and establishes procedures for securing the future for our diversity of species and their habitats. The plan highlights terrestrial, inland aquatic, and coastal habitat conservation needs and targets specific species that require both rapid and long-term intervention.

The Wildlife Action Plan makes one thing immediately clear. Ask any Texan to list the number of native species and the best results will provide a list of a half dozen popular critters - the Texas horned lizard, Attwater's greater prairie-chicken, Texas snowbells, the black bear, the Comanche Springs pupfish and the Comal blind salamander among them. But considering the large list of species and habitats addressed in the plan, Texans will quickly realize that the bulk of the state's endangered and threatened are significant in number but neither charismatic nor well-known.

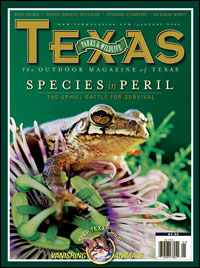

The sheep frog (Hypopachus variolosus) is one of those species you don't hear about very often. This oddly proportioned amphibian burrows for most of the year under logs and dines mainly on ants and termites. Its small head and pointed snout are paired with a bulbous body, giving the sheep frog the comic appearance of a big man with a tiny head. Although sheep frogs are known to emerge from their burrows after heavy rains, they remain hidden for much of their lives, making population assessments difficult. On the other hand, the pig frog (Rana grylio), often mistaken for a bullfrog, was once a common sight floating among the aquatic plants of ponds and tanks. It derives its name from the grunt-like sound it makes and any Texan who ever enjoyed frog-gigging as a kid will recognize the pig frog's call even if they haven't heard it in decades. Texas harbors 43 species of frogs and toads total. Yet we know remarkably little about most of them, including the sheep and pig frogs, other than the fact that due to loss of habitat their populations in general are at risk. Some species of frogs and toads, in fact, have begun to produce a concerning number of malformations. Frogs and toads in particular are often considered "canary in the coal mine" species, signaling detrimental changes in the health of the environment. These changes are often noticed only when they affect local populations but they tend to have global ramifications.

Nowhere is this clearer than in our birds, wildlife that rely on a selection of habitats, sometimes thousands of miles apart, for their survival. The high profile whooping cranes, peregrine falcons and bald eagles are all birds of Texas that receive attention for their threatened and endangered status. But what about the lesser known Eskimo curlew (Numenius borealis) and its varied migratory habitats? In the past, this 12-inch shorebird was one of the most common birds along the American coastline. It is thought that the millions of migrating Eskimo curlew were one of several likely bird populations to have drawn Christopher Columbus to land. Its migratory pattern extended from the tundra of the western Arctic to the pampas of Argentina, making Texas a stopover location along its spring route. Unregulated hunting reduced the population dramatically during the late 1800s but by 1916 the bird came under the protection of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. However, the transformation of the bird's migratory grounds - the American prairie and the South American pampas - into agricultural fields guaranteed the Eskimo curlew's continued decline. The last confirmed documented sighting in Texas occurred along Galveston Island in 1963. Twenty-three additional unconfirmed sightings have been reported since then in Texas, Canada, Argentina and Nova Scotia. Although the bird remains on the endangered list, it's possible that the Eskimo curlew is extinct.

Other bird species of concern may still have a good chance of surviving should Texans decide to ensure their future. The ferruginous pygmy-owl (Glaucidium brasilianum) is another of dozens of birds that have been brought under the Texas Wildlife Action Plan. A mere 6 inches tall with extremely large talons, the owl nests in tree hollows or manmade nest-boxes. Its subspecies, the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl (Glaucidium brasilianum cactorum), was removed from the federal endangered list due to successful litigation by development groups rather than because of any improvement in its population numbers. However, both birds remain as special concerns nationwide, and the cactus ferruginous pygmy-owl is listed as threatened in Texas. Loss of habitat, once again, is responsible for this bird's decline.

Several mammalian species in Texas experienced significant population declines during the past century, but there are rare examples of species restoration. The state's desert bighorn sheep populations (ovis canadensis nelsoni, ovis canadensis mexicana) are one such example. Although the native bighorn was extirpated by the 1960s, translocations from Nevada, Arizona, Utah and Mexico helped Texas to kickstart its restoration program. Intensive management during the initial years resulted in only modest increases in bighorn numbers and distribution. However, continued efforts by TPWD, the Texas Bighorn Society and private landowners resulted in a four-fold increase during the past decade from less than 300 sheep to an estimated 1,200 - numbers that are approaching historic estimates.

In contrast, efforts on behalf of black bear and Mexican wolf have been faced with extreme controversy and insurmountable obstacles. Our mammals of the Gulf of Mexico are perhaps no better off as they attempt to survive in an environment difficult to regulate, almost impossible to patrol, and under siege by overfishing and climate change. Oceanic species listed in the Texas Wildlife Action Plan include the pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata), a cetacean in the dolphin family believed to range throughout the tropical and sub-tropical waters worldwide including Texas. The state documented three that have been stranded and a pod that was sighted off the southern coastline to date. Elsewhere, pygmy killer whale sightings are equally rare, possibly due to its aggressive, uncooperative nature. However, so little is known about this species that most behavioral and population data are anecdotal. Consequently, humans might never know at what point this species reaches its moment of demise.

Many of the species listed in the Action Plan behave in a cryptic manner, making monitoring and population counts extremely difficult. But nothing can act more cryptic than any one of the thousands of insects that populate our state. Disconcertingly, cave spiders, mold beetles and a catalogue of little-known species occupy the Texas Wildlife Action Plan pages. Yet we may never know some of the bugs we're losing because the state's entomologists have yet to complete the list of invertebrate species in Texas. This fact illustrates our harshest reality: We understand very little about our natural world but we have come to realize that each component is somehow integral to the health of the entire system. Eliminate or dramatically alter a few of the elements slowly over the course of a millennium and perhaps the change is relatively minimal. But alter the habitat significantly and eradicate many species as we have done over a brief span of time and the results may create a future for our children that may be untenable.

Texans have the power in their hands to change the course of the state's diminishing natural world. It is our responsibility and it will be our legacy. The Texas Wildlife Action Plan provides a careful and concise way for our professionals charged with the protection of our environment to do so. Our own challenge is to ensure that our leaders heed the will of the people and continue to support this important work. To do otherwise could easily put future Texans on the endangered list as well.

What is the Texas Wildlife Action Plan?

Completed in 2005, the Texas Wildlife Action Plan will conserve wildlife and natural places and enhance our quality of life. With the urbanization of Texas - Census Bureau estimates released in March 2008 show four Texas metro areas in the top 10 fastest growing communities in the U.S. - this plan will guide us in meeting our commitment to conserve wildlife and habitat. It forms a framework that can coordinate strategic planning and identify problems and solutions on a statewide scale.

The plan prioritizes eco-regions, river basins and wildlife species across the state in need of attention for research and management purposes, with goals established for meeting those needs. Input was sought from across the state through a statewide Wildlife Diversity Conference and a series of public meetings.

The conference brought together professionals involved in wildlife management and established species-based working groups to identify issues, gather information and create a list of priorities to form the basis of the plan. These groups spent six months gathering information and the next six months developing the final draft of the plan itself.

Another source was the prior planning done by TPWD and others that identified existing conservation needs in the state. This provided continuity and consistency into the future.

Public input was sought through online comment on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Web site and through a program at 11 public venues across the state.

The plan provides guidance by directing conservationists toward key questions that need to be answered to manage wildlife in Texas. This is one of the roles of the plan - to reconnect people to the wonders of Texas' unique natural resources while stimulating discovery of solutions to the conservation challenges of the future.

The plan brings funding to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department in the form of State Wildlife Grants. These grants are used to address the needs of priority species and their habitats in the 10 ecological regions using department staff, private landowners and other partners. By outlining and prioritizing the species and issues in greatest need of attention, the plan steers grant processes toward management actions and research necessary to solve conservation problems.

The Texas Wildlife Action Plan provides guidelines to ensure wildlife, fisheries and habitats a place in Texas. Guidance, research and actions recommended across the state will come from a common source, providing consistency and continuity. This will help conservationists work cooperatively. The plan is available online at www.tpwd.state.tx.us/twap.

- Mark Klym