From the Pen of Carter P. Smith

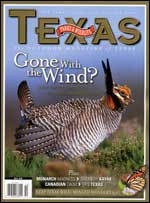

Of all the possible names that could have been conjured up for one of the signature bird species of the southern Great Plains, “lesser prairie-chicken” has to be one of the more unfortunate. Clearly, it is not the bird’s fault that it has been labeled with a name that neither inspires nor elicits much sympathetic concern. That is too bad. In the coming years, the lesser prairie-chicken is going to need every bit of help it can get to persist in the wilds of the Texas Panhandle.

The lesser prairie-chicken, or in conservation parlance, the “LPC,” is a denizen of the expansive grasslands still found throughout the Texas Panhandle, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Kansas and Colorado. The colorful and highly ritualized mating dances of male LPCs performed on their spring breeding grounds, or “leks,” are the stuff of legend. The bird’s elaborate booming and strutting are said to have inspired certain dances performed by Native American tribes. Believe me, the dances are magical, visceral and worth observing, if you ever get the chance.

Regrettably, LPCs appear to be going the way of their coastal cousins, the endangered Attwater’s prairie-chickens, which have dwindled to such low numbers that they are holding on only by virtue of an aggressive captive breeding-and-release program. According to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologists and other scientists, Texas’ LPC populations have dropped over 90 percent from their historic highs. The culprits for the LPC’s decline are familiar ones — conversion of grasslands to croplands, habitat fragmentation, urbanization and incompatible oil and gas development.

Today, the birds may only be found in a dozen or so Panhandle counties, largely around the community of Canadian, as well as southwest of Lubbock near the New Mexico line. Thanks to efforts from private landowners, as well as biologists from TPWD, the Fish and Wildlife Service, The Nature Conservancy and others, there is still potential for enhancing the bird’s habitat, and hence conservation, of this imperiled species.

This part of the state, however, also harbors great potential for something else, a feature already well-known to citizens of the Texas Panhandle — wind. The readily available supply and predictability of Panhandle wind resources, substantial local, state and national tax incentives and aggressive renewable energy portfolio goals have spawned a literal wind rush in areas occupied by the remaining LPCs. With it are coming miles and miles of new 345 kV transmission lines in order to move wind-generated energy to more populous parts of the state.

Suffice it to say, wind energy development is a welcome economic development for some Panhandle landowners and communities. For Texas LPC populations, it is probably not. These grassland birds evolved in open, prairie landscapes, places bereft of trees. Anything tall in the grasslands usually means habitat for predators like hawks and owls. As researchers in Kansas and Oklahoma have shown, LPCs deliberately avoid using available habitat close to transmission lines and wind turbines, likely because of this association with roosts for predators.

As you will read in the accompanying article by Stayton Bonner, there is a storm brewing in the Panhandle over wind and prairie-chickens. Having gone through a few endangered species conflicts in my career, I’d rather not see LPCs become the golden-cheeked warblers of the High Plains. Avoiding such a scenario is possible, but it will require a newfound level of cooperation between wind developers, state and federal agencies, environmental groups and, of course, our Panhandle landowners. At Texas Parks and Wildlife, we stand ready to do our part.

Thanks to all of you for caring about Texas’ wild places and wild things. They need you more than ever.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department mission statement:

To manage and conserve the natural and cultural resources of Texas and to provide hunting, fishing

and outdoor recreation opportunities for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.