Pineywoods Pocahontas

Friendly Angelina bridged cultures, serving as a guide to the French and Spanish in Texas.

By Russell Roe

She’s been called the Texas version of Sacajawea and the Pocahontas of the Pineys. She’s the only woman for whom a Texas county and river are named. A national forest bears her name as well.

Who is she? She’s Angelina, a Native American woman who befriended the early Spanish mission priests and served as an interpreter and guide for French explorers.

Most Texans have probably never heard of her, and her life remains shrouded in mystery and romantic legend. It’s been 300 years since she inhabited East Texas’ forests, after all. Her name lives on, however, in Angelina County and the Angelina River, and she remains entrenched in the history of East Texas.

“She’s a great historical figure,” says Bob Bowman, an East Texas historian and author. “It enriches East Texas, the Angelina story.”

Jonathan Gerland, the director of the History Center in Diboll, uses her story when telling people outside the area about his work.

“Instead of first saying we’re near Lufkin, I proudly say, ‘We’re in southern Angelina County, the only county in the state named for a woman,’” he says. “It always brings out a reflective, pondering expression of, ‘I never knew that before.’ Nearly everyone, male and female, seems pleased with the observation.”

Angelina appears in a mural in Lufkin, the county seat of Angelina County.

Angelina’s first recorded appearance comes at the time of the establishment of the first Spanish mission in East Texas, San Francisco de los Tejas, in 1690. The mission, near the Neches River, was set up to spread Christianity and to keep an eye on the French, whose intrusions into the area were a cause for Spanish concern. The La Salle expedition had shifted the Spanish focus from western Texas to eastern.

Mission leader Father Damian Massanet, in his visits to a Hainai village, came across a native girl who possessed a bright intellect, a striking appearance and friendly personality. The Hainai were the head tribe of the Hasinai confederacy, part of the Caddo nation. The girl expressed a desire to learn Spanish, and she began to help the missionaries.

The Spanish priests and soldiers, charmed by the cheerful nature of the girl, gave her the name Angelina, or little angel. They called her village Angelina’s village, and they called the stream nearby Angelina’s river.

In 1693, the missionaries, facing harsh conditions and growing suspicions from the Indians, abandoned the mission, and Angelina went with them to Mexico to pursue her studies. She studied at Mission San Juan Bautista, the gateway to Spanish Texas, south of present-day Eagle Pass, where she grew proficient in Spanish and joined the church. After a decade, she returned to East Texas.

Angelina appears in the journals of Spanish missionaries and French explorers as a guide, mediator and interpreter between the native tribes and the Spanish and French. Since the native tribes left no written record of the time, what we know of Angelina comes only through the Europeans. In 1712, a member of the party of French Canadian explorer Louis Juchereau de St. Denis noted that a woman named Angelique, “who had been baptized by Spanish priests on a mission to their village,” helped St. Denis hire guides from her tribe.

Spanish ventures in East Texas generally came in response to French activity. In 1716, the Spanish returned to establish missions and presidios in East Texas, and a member of the Domingo Ramón expedition wrote that the group “had recourse to a learned Indian woman of this Hasinai tribe.” The Spanish re-established Mission San Francisco de los Tejas, and they established a companion mission in Angelina’s village, Mission Concepción. The mission lasted until 1719, when the Spanish withdrew during the Chicken War with the French.

In 1718 and 1719, Angelina translated for an expedition that founded the Alamo in San Antonio, and was described in a journal as a “sagacious Indian interpreter.”

Angelina is also believed to have rescued French officer Francois Simars de Bellisle, who was marooned near Galveston Bay in 1719 after overshooting his intended destination of Louisiana. Bellisle’s four companions died of starvation or exposure that winter, but Bellisle managed to stay alive by eating oysters and worms. He was captured by coastal Native Americans who treated him as a slave, and was subjected to cruel treatment and hard labor and forced to stay naked. Bellisle managed to write a plea for help and gave it to visitors with instructions to deliver it to “the first white man.” The note ended up in the hands of St. Denis, who sent Hasinais to rescue the castaway.

Bellisle stayed with Angelina at her village while he recovered. Angelina “served me with all the best she had, and she had as much love for me as if I had been her child,” Bellisle wrote. “This Indian woman, called Angelica, had lived with the Spanish since her childhood. That is why we understood each other so well.” Angelina sent her two children to guide him to Louisiana, and he reached the French post at Natchitoches in February 1721.

The final written account of Angelina comes in 1721, when the Spanish returned to East Texas to re-establish the missions abandoned after the French invasion of 1719. Angelina was among the group of leaders who welcomed the expedition of Marquis de Aguayo to her village, and she served as the group’s interpreter “because she could speak the language of the Spanish as well as the Tejas,” a member of the expedition wrote. Angelina helped revitalize the missions in the years to come.

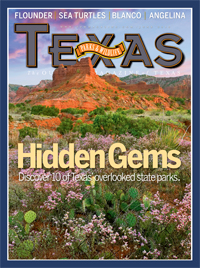

An East Texas national forest is named after Angelina, as are a county and river.

With her name attached to a county and river, Angelina continues to have life to this day in East Texas.

“The fact that we have a county named after her gives some weight to her legacy,” Gerland says.

Without that, she might have become obscured in the mist of history. The river has carried her name for centuries. The county took her name when it was broken off from Nacogdoches County in 1846 (the Angelina River divides the counties). Angelina National Forest was established in 1936.

And if you drive around Lufkin, the Angelina County seat, you’ll see her name and image. A statue of Angelina stands outside the Lufkin Civic Center. A striking, 30-foot-tall face of Angelina looks out over Cotton Square in downtown Lufkin as part of a historical mural done by artist Lance Hunter in 1991.

Hunter sees Angelina as a pivotal figure. “I saw her as the starting point to represent the Native American population and also certainly her assistance with the early Anglo settling of the region. The strands of her hair are reaching into the future,” says Hunter, who also painted Angelina riding on the front of a train in another Lufkin mural.

Around the county, there’s Angelina College, Angelina Playhouse, Angelina Title, Angelina Counseling, Angelina Manufactured Homes and Angelina Bath and Custom Marble. Here’s a business idea: Angelina Guiding and Interpreting Services. There’s Angelina Church of Christ, but no Angelina Catholic Church. To the folks at Angelina Septic Tank Cleaner: Come on, let’s have some respect here. We’re talking about one of the first women of note in Texas history.

The name Texas comes from “tejas,” which is the Caddo word for “friend.” The state motto “Friendship” is also derived from this. The Spanish missionaries called the Caddo homeland “the kingdom of tejas,” and that name became the name of our state. Texans still pride themselves on their friendliness.

By all accounts, the Caddoan Angelina was a friendly, welcoming person, bridging cultures and helping those who played an early role in what became our state. She exemplifies the idea of “tejas.” Could it be, then, that Angelina, the “little Indian maiden,” is the person who best represents the ideal that gave Texas its name and identity? Maybe we should name something else for her, or at least consider that she might have been Texas’ first friend.