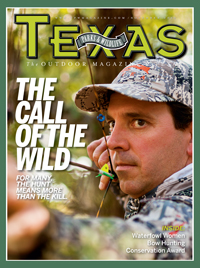

The Draw of the Bow

Heritage, training and technology come together for a memorable first bow hunt.

By Reid Wittliff

I grew up in Central Texas in the 1970s and ’80s. Most of my childhood friends spent at least a couple of weekends each fall with their dads in a deer camp.

I didn’t. For whatever reason, my dad was not into deer hunting.

Not that I didn’t get my fair share (and maybe more) of time outdoors with my dad. He loved to fly fish, and I learned early. Even so, I always had the itch to hunt. Maybe it’s in my genes. My grandmother and her father both regularly hunted deer. He was a Texas German named Emil Sachtleben. Born poor in Blanco County in 1881, he lived a tough, hardscrabble life.

The author’s grandmother and stepgrandfather, with memories of past deer hunts on the wall.

One of his few recreational joys was deer hunting. He didn’t hunt from a stand or near a feeder. He liked to roam the woods, find a tree and sit at its base to wait for a deer to walk by.

My grandmother loved to hunt, too. After my dad and uncle were grown, she hunted each fall on her ranch in the Texas Hill Country. She used a weathered .30-30 rifle with a cut-down stock that fit her small frame perfectly. Grandma never hunted in camo. She wore farmers’ coveralls and a bright orange knit cap.

I have the antlers from her last buck hanging on a wall. The plaque bears her name, the date and “Age 89.”

Grandma’s last buck, taken at age 89.

Once, when I was about 12, my stepgrandfather “Pop” took me hunting on Grandma’s ranch. I was nervous and excited. When a buck walked in front of the stand, I watched it through the scope.

“Go ahead, lower the boom on him,” Pop said, and I pulled the trigger. The buck fell. Then he got up and ran. We spent the next two hours, one in pitch-blackness, searching for him.

We found him, but I ended up with a sour taste in my mouth from the fear of losing him. I didn’t hunt deer again for 30 years.

Deer hunting came back into my life after Grandma passed away and I became the steward of her Hill Country ranch. There is no live water on the property, and that part of the Hill Country doesn’t offer much in the way of bird hunting. But there are deer. A lot of deer.

When I took over at the ranch, I decided I should hunt them, because I needed to reduce their numbers, because I thought it might be fun and because I felt some pull to carry on where Grandma left off.

That first season, I hunted from an old wooden stand some lease hunters had scabbed together. I put up a feeder about 100 yards from the stand. I sat in the stand three or four times that fall and saw numerous does and a couple of good bucks. I decided to shoot only does because I knew we had too many. Twice I “lowered the boom.” I made good shots and had easy recoveries.

That first year back in the stand, I found that I enjoyed the sitting, waiting and watching more than the actual shooting. I saw a lot of nature from the stand — birds, squirrels, an occasional armadillo or raccoon — and I watched as thunderstorms rumbled in the distance or as a burnt orange sun dipped past the horizon.

But I found something about shooting deer with a rifle lacking. When I went fly fishing on the coast, I knew a skilled presentation and deft line-stripping and hook-setting meant the difference between fish and no fish. Rifle hunting, in contrast, felt preordained. The deer did not have much of a chance.

After that first season, I wasn’t sure I would continue to deer hunt for pleasure. I figured I would shoot a deer or two each year for venison and for population control, but I thought it would be more chore than recreation. Then I was introduced to bow hunting.

I have friends who are both fly fishermen and bow hunters. One buddy I’ve fished with for years had long been after me to try bow hunting. He finally got my attention one day when I was telling him about rifle hunting on the ranch.

“Really,” he said, “you’ve got to try it with a bow. It’s the fly fishing of hunting.” Then he showed me his hunting bow.

Like fine fly rods, modern bows are things of beauty filled with technology. Crisscrossed strings wind around nautilus-shaped cams. Harmonic dampeners sit inside the bow’s limbs to reduce noise and vibration. A peep sight is interwoven in the bow string and aligns with fiber-optic pins for aiming.

They are, in a word, cool.

I outfitted myself with a new bow and all the accoutrements. I then began the process of learning to shoot it.

I am not a golfer, but I imagine learning proper archery technique is akin to trying to master a golf swing. There is a proper stance, manner of nocking an arrow and technique for drawing the bow. Your bow-hand grip is critical. Counterintuitively, you must hold the bow loosely, with a relaxed hand and arm, to avoid torquing the bow and slinging the arrow off-target.

Your anchor point, the place where you rest your release hand on your face, is equally important. It has to rest in the exact same location for each shot to be consistent.

Modern bows are complex pieces of equipment.

Great archers learn to aim and release their arrows without consciously meaning to do so, a so-called surprise release. The whole process has a sort of yin/yang to it. Strength, relaxation, focused thought and a clear mind all play a part. There are times you think you will never get it and other times when it just seems easy. When you do get it, the sensation is not unlike casting a fly rod — smooth, graceful and quiet.

Shooting a bow is only half of bow hunting. The art of hunting is just as involved, if not more so. You must be close — for me, 30 yards — to the deer while remaining undetected to be successful. This is not easy. Deer have keen eyesight and a hyper-alert sense of smell. Many bow hunters opt to hunt from a tree stand because the height removes the hunter from the deer’s line of sight and, hopefully, raises his scent above the deer.

Each day after work, I practiced with my bow. When the season approached, I purchased a metal ladder stand and set it up in a tree near a game trail and a little opening ringed with oaks.

One day, driving to this spot, I saw a thick-necked buck with a beautifully symmetrical and wide eight-point rack. He was unlike any buck I had seen on the ranch. I vowed to hunt for him during the upcoming season.

In Texas, like most places, there is a special archery season that opens a month before rifle season, typically around Oct. 1. I had other plans the first weekend in October, but was free the next weekend. This would be my first bow hunt.

Dressed head-to-foot in camo clothing, washed in a special soap to hide my scent, I walked quietly to my stand in the ring of oaks. I tied my bow and quiver to a rope and climbed up. I secured my harness and pulled up my bow. I put on my release, nocked an arrow and sat for a minute to get my bearings.

A productive bow hunt depends on a smooth, quiet and accurate shot. The hours of preparation and practice come down to the split-second of an arrow’s release.

I was in the stand early in the evening and planned for a long wait.

To my surprise, about 15 minutes later, I heard steps approaching from the right. I slowly pulled my bow from where it was hanging and inched forward on the platform.

I heard another few steps, heavy steps. My palms were sweaty. I slowly cocked my head to the right and peered through the leaves. Another step. Then, I saw the top edge of an antler emerge.

I debated whether to draw my bow before the buck came into full view. I decided to do so. I extended my left arm, carefully and softly wrapped my left hand high on the bow handle, attached my release and slowly drew the string. I anchored on my face and rotated the bow to where I expected to see the deer emerge into the open.

A few seconds later, a tall-tined nine-point buck walked within view. He was perfectly broadside, big-shouldered and mature. He had a beautiful rack. I had never seen this deer before.

He was amazing.

I watched the buck through the peep sight and placed the pin just below mid-body, in line with the back of his front leg. I second-guessed my decision to try for only the symmetrical eight-point buck. And then, without consciously meaning to do so, I let down the bow and let out my breath as quietly as I could.

Within minutes, five or six does joined the nine-point buck at the feeder. I kept still and watched as the does fussed at one another. The buck ignored them. There were now six or seven deer within 15 or 20 yards of my perch. It was mesmerizing.

I heard steps again. This time they were coming from behind me, the downwind direction. I carefully got my bow ready.

The steps stopped, and the unseen deer stamped its hoof, then snorted. The does at the feeder snapped up their heads. The downwind deer angrily snorted again and sprinted away. The other deer instantly bolted, leaving only settling dust. It was about 6:30 p.m., and I was sure the hunt was over. I hung up my bow and planned to wait for the sun to set.

About 30 minutes later, I thought I heard a rustle to my left. I cocked my head and listened intently. I heard slow steps. My heart picked up its pace. I pulled up my facemask and reached for my bow. I heard steps, a pause, more steps. Then, just above a pile of cut cedar, I saw the nose and long, distinctive antlers of the symmetrical eight-point buck.

He stood staring straight ahead and still. I tried to maintain a steady breath. He took six more steps and stood broadside, right in my shooting lane. As slowly as I could, I drew the bow.

I forced myself to ignore his rack and focused on a spot just behind his shoulder. I anchored my release and told myself to relax.

I aimed the sight pin and gently released the arrow.

The arrow flew straight, and the shot felt smooth. The buck leapt and kicked his rear legs high in the air. He landed, wheeled back the way he had come and was gone.

I was dazed and just shy of hyperventilating. I hung up the bow and replayed the shot in my mind. I hoped it had been a good shot, but I couldn’t be sure. Best to wait, I told myself. I checked my watch and committed to wait at least 30 minutes.

The author and his dog, Belle.

Those 30 minutes seemed like an eternity. At last, I climbed down from the stand. I found the arrow. I began searching the area near where the buck had stood for spots of blood but found none. I grew anxious, second-guessing my shot. My gut tightened, and I thought of the last time I had searched for a buck, 30 years before.

I slowly walked down the trail the buck had used to come to the feeder. I scanned the ground and leaves. I circled back and decided to drop down the slope behind the feeder. Nothing.

The sun had set and light was fading. I was worried. I turned left to make a third loop. Hunched over, I searched the ground. I stopped and glanced up.

There he was, head erect and his wide, symmetrical antlers wedged through a persimmon tree. The shot had been good. A wave of relief washed over me, and I went to him. He was beautiful.

As I sat there alone in the twilight looking at the buck, I felt no desire to whoop or pump my fist in the air. What I did feel was bone-deep satisfaction and humbleness.

Later, I had the buck mounted, and it hangs near the antlers of my grandmother’s last deer. She would have shared in the joy of this hunt and in my becoming a bow hunter.

Related stories

Shoot That Fish: Bow Fishing Turns Angler into Archer

Digital Extra: Texas Hunting 2012

Hunting on High: Selecting a Tree Stand