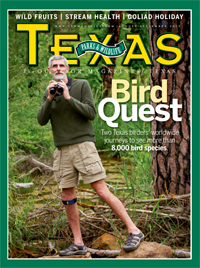

The 8,000-Bird Club

Two Texas birders find high adventure in their quests to see most of the world’s avian species.

By Russell Roe

David Shackelford can recall the moment that changed his life — the moment that set him on a path to become the youngest person to see 8,000 bird species. As a teenager at Pedernales Falls State Park, where his dad was superintendent, he was scrambling up a rock face to get a closer look at a plant when he noticed a golden-cheeked warbler. It fluttered around and landed on his finger.

“In that moment, I could see each and every feather, all the details of its face,” Shackelford says. “It wasn’t just a bird sitting on my finger; it wasn’t just the magic of having the interaction. It was a connection.”

For Phil Rostron, his connection with birds came at age 12, when he began birding with his father in his native England. They started by trying to identify the birds in their local park. “We had a little bird book and started noting down what we were seeing,” Rostron says. That first list transformed into a quest that has taken the Bastrop resident to every continent, some multiple times.

Shackelford and Rostron are “big listers,” birders who have trekked around the globe on unending missions to see and log thousands of birds for their birding “life lists.” Both have attained the rarefied 8,000-species level, an accomplishment reached by only a couple of dozen people in the world. There are about 10,000 recognized bird species.

Rostron’s 8,700 birds make him No. 4 in the world rankings of birders on Surfbirds.com. Shackelford is No. 10 (No. 8 among active listers).

It’s quite a feat to see 8,000 bird species. Dedicated birders with a lot of time and money can reach 4,000 or 5,000 after years of regular travel. Reaching 8,000 requires an obsessive dedication, an insatiable wanderlust, time for long-term trips, the means to pay for such trips, a tolerance for Third World travel, sharp organizational skills, vast ornithological knowledge, a willingness to risk danger and the ability to find birds in challenging circumstances.

Being a big-lister requires traveling not just to every continent but to most regions of most continents. It means multiple trips to hot spots such as Peru, China and Madagascar. Big-listers have spent so much time in the Amazon that the birds start to recognize them when they visit. To see more, they have to spend days at sea to spot oceanic birds and hop from island to island in the Indian Ocean to check off island-specific birds.

Why the compulsion to see and list so many birds?

Birds are beautiful, charismatic, accessible and endlessly fascinating. And listing is a central component of birding. For birders, listing lets them keep track of what they’ve seen and can focus their activities. Lists also add a gaming aspect, ushering in a competitive element. And who isn’t a little competitive? It all gives rise to what birder and field guide author Roger Tory Peterson calls “the lure of the list.”

A birder’s life list is just one form of listing. Birders also keep yard lists, park lists, state lists, country lists and trip lists. Birders embark on Big Days, where they try to see as many birds as possible in one day, and Big Years, where the concept is extended to an entire year.

The world of listing is peppered with tales of obsessive types who drop everything and dash off to see a reported rare bird, who miss family weddings and birthdays for travel, who strain marriages and finances in the mad pursuit of birds.

Scott Weidensaul, author of Of a Feather: A Brief History of American Birding, sees birds at two extremes — as a source of awe and inspiration and as tick marks on a list, treasures in a scavenger hunt. Most birders exist somewhere between those two poles and incorporate elements of each.

Everyone’s list is different. Some birders include details of a bird sighting; some just check it off. Some birders share their lists; others keep them to themselves. Some birders include heard-only birds; some don’t. It’s all done on the honor system.

Surfbirds.com has bird lists broken down by continent, nation and state, and also has world life lists of insects, reptiles and mammals (Shackelford is No. 4 in mammals). The American Birding Association also keeps birding lists.

A son of state parks

If you’re looking for a fanatical birder who’s more fixated on numbers than on birds, Shackelford’s not your guy.

“The best part of birding is sharing it with other people,” says Shackelford, 32.

.SHACKELFORD_6779.jpg)

David Shackelford worked as an international bird tour leader for Rockjumper Birding Tours.

He agreed to share some birds with me at Pedernales Falls, where he lived as a teenager. He especially wanted to find a golden-cheeked warbler, the bird that started it all for him.

We walked down a trail and stopped on a cedar-covered slope, prime warbler habitat. He heard a golden-cheeked warbler and found it in his spotting scope. With the naked eye, it looked like a dot in a tree. Through the scope, the brilliant yellow color jumped to life.

The endangered golden-cheeked warbler gave David Shackelford his first real connection to birds.

Shackelford realized that by learning about birds and their habitats, he’d learn about the ecology of the world.

He worked as an international bird tour leader for Rockjumper Birding Tours and was able to see more birds in a decade than most dedicated birders will see in a lifetime.

“Birds have conquered every habitat on earth,” he says. “You walk out your front door, birds. You go to Iceland, there are birds. You go to Antarctica, there are birds. You go to the highest mountaintops, there are birds. They specialize in volcanoes; they specialize in cloud forests; they specialize in the highest reaches of grasslands. You can be out in the middle of the Serengeti in Africa and you’re going to see bright, colorful, gaudy birds. You suddenly realize there’s this endless variety of birds. The more you learn, the more interesting it becomes.”

He and his dad, Pedernales Falls Superintendent Bill McDaniel, started birding together. They’d spend time in the field — “really joyful times for me,” he says — trying to pick out the identifying marks of sparrows.

After college, Shackelford moved to the Amazon and got hired by Rockjumper. His quest to see all 200 or so bird families took him to all corners of the earth, and his bird list started growing quickly. In 2009 and 2010, he saw more birds than perhaps anyone in the world. He says you could drop him anywhere in the world and he’d know where he was, based on the birdsong.

For Shackelford, finding a rare species can be like discovering gold at the end of the rainbow. In the jungles of Borneo, he was on the hunt for the Bornean ground cuckoo, a secretive, rarely seen bird. He was camping out, watching proboscis monkeys in the trees, knowing he was getting closer, feeling his anticipation grow.

“Then one morning you hear the call of the Bornean ground cuckoo echoing like this ethereal call through the forest,” he says. “You’re crawling on your hands and knees. Your adrenaline is going; you’re sweating; you’re tired; there are bugs everywhere. You think, why would anyone choose to be doing this? Finally, you catch a shadow. And then, there it is in your binoculars — the Bornean ground cuckoo. You have so much appreciation for this bird now. Why birds? That’s like ‘why breathe?’”

Shackelford says his list is full of incredible memories.

“The life list is not just a list. I can go down that life list and look at the birds I’ve seen, and there’s a story attached to each one of them,” he says. “It’s a collection of experiences.”

Shackelford has had plenty of experiences. He’s wrestled an anaconda in the Amazon, been caught in the middle of a gunfight in Madagascar and seen tigers from the back of an elephant in India.

Now Shackelford has switched gears. He returned to Austin, earned a master’s degree in health care administration and became a parent.

“Something I learned along the way is there’s always going to be another bird,” he says. “But family is a one-time shot.”

World traveler

For Rostron, birds have been a way to see the world.

Rostron, 55, typically takes three or four international birding trips a year. When you do that for more than 30 years, it adds up to a lot of trips. He took his fifth trip to China in May. He’s been to South America more than 30 times. Name just about any place in the world, and Rostron has been there.

Phil Rostron's goal was to see half the world's bird species by the time he was 40.

While living in California, his first long-distance birding trip was to Texas — to Bentsen-Rio Grande State Park near Mission, one of the nation’s top birding destinations. He’s been traveling to see birds ever since.

Rostron moved to Texas in 1991 to work in the tech industry, where he was lucky to have a “sympathetic boss” who let him take extended time off to travel.

His goal was to see half the world’s bird species by the time he was 40.

“I never really had any specific goal beyond that,” he says. “It was more a question of, there were lots of interesting places I wanted to go see and lots of interesting birds to go see. The numbers just came along.”

After that job ended in 1998, Rostron took off almost two years to travel and look for birds. Contract work and frugal living have let him splurge on his bird trips, which have brought him experiences from the sublime to the absurd.

Take the Kolombangara leaf warbler, found only on the island of Kolombangara in the South Pacific. To see it, you first have to get to the Solomon Islands, a remote group of a thousand islands east of Papua New Guinea. Then you have to get to the island of Kolombangara. Once you’re at the island, you have to hike up a volcano, from sea level to 5,000 feet in elevation. Then you have to find the warbler, which lives near the top of the volcano. Then you hike back down.

“You have to be pretty nuts to see that bird,” Rostron says.

His travels have also brought him moments of beauty and joy.

“I always wanted to see the red-crowned cranes dancing in the snow,” he says of a trip to Japan in winter. “I’d seen them on Japanese postcards. To experience that, finally, to see them dancing in the snow in winter, was a great experience.”

Seeing red-crowned cranes dancing in the snow in Japan was a birding highlight for Phil Rostron.

Rostron’s “cost per bird” keeps going up, a common problem among top birders. On his early trips, he might see a couple of hundred new species. These days, he’s lucky to get 20 new birds.

Rostron has had his share of adventures along the way. He was almost killed by a runaway truck in Brazil, and he was detained in Jordan on suspicion of espionage (lesson learned: don’t go looking for birds with binoculars near the Jordan-Israel border).

And then there was the fire. Rostron lost his house when wildfires swept through Bastrop in 2011. He was on a birding trip to Angola when it happened. He lost his bird books, his birding history, including pictures of his dad when they started birding. Thankfully, he had his bird lists online.

“It was devastating,” Rostron says. “All I had with me was one small bag. Everything else was gone. I came back with a backpack as my worldly possessions.”

Bird by bird

Through birding, Shackelford and Rostron have seen some of the world’s wildest and most remote places.

But traveling the world isn’t necessary for great birding. Texas is incredibly birdy, and with our diverse habitats and location in the migration corridor, birding brings the world to us. Whether we keep a life list, a yard list or no list at all, we can all enjoy the miracle that is a bird.

“You don’t have to travel to far-flung locations in order to have incredible experiences,” Shackelford says. “All you have to do is look out your window in your backyard.”