Love at Second Sight

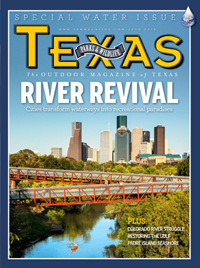

Texas cities are embracing their rivers again.

By Russell Roe

In 1718, Spanish missions started to appear along the San Antonio River near its headwaters. In 1836, the Allen brothers staked out a spot along Buffalo Bayou and named it after Sam Houston. In 1841, John Neely Bryan founded Dallas when he built his cabin near the Trinity River. Farther west, Maj. Ripley S. Arnold established a frontier fort, Fort Worth, at the confluence of two forks of the Trinity.

Texas cities were built on rivers. But for decades, many cities have abused or ignored their rivers — straightening them, walling them off with levees and using them as dumping grounds. Many residents never felt connected to them.

That’s starting to change. Cities are realizing what incredible resources their rivers are, and many of them are embracing their rivers once again. Several major cities are embarking on ambitious public works projects to revitalize their waterways. People are tubing on the Trinity in Fort Worth, bird-watching along the same river in Dallas, biking on new trails along the San Antonio River and paddling the waters of Houston’s Buffalo Bayou. Austin is finishing a boardwalk on Lady Bird Lake and digging a flood tunnel to enhance downtown’s Waller Creek. Waco, Arlington and other cities have also undertaken extensive waterfront transformations.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has assisted many of the projects with trail grants, habitat assessment and environmental planning.

“People’s thinking about rivers has changed quite a bit,” says Tom Heger, watershed conservation team leader for TPWD. “It’s not just about flood control. Now, it’s like, ‘Hey, there’s this thing that could be a real amenity.’ There’s better, more clear thinking about how to protect and utilize a river.”

Andy Sansom, executive director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment at Texas State University, says Texas rivers are in much better shape than they were 50 years ago in terms of water quality, particularly in urban areas.

“In addition to being an increasing amenity for urban life, rivers are also a success story in terms of environmental progress,” he says.

Sansom sees the current projects as part of a continuing effort to improve urban life in Texas.

“One of the positive things about urban life in Texas right now is that all these cities are attempting to upgrade the urban core,” he says. “They’re becoming destinations where people want to live and work and play. Rivers are a part of that.”

Dallas

In the shadow of downtown Dallas, we pushed off in our canoes and headed down the Trinity River into the 6,000-acre Great Trinity Forest, one of the largest urban hardwood forests in the nation. Who knew this was here?

“We’re in the middle of 5 to 6 million people, but along the river, it’s wilderness,” says our canoe guide, Charles Allen.

Sure enough, in the six miles of the trip, which is a designated TPWD paddling trail, we saw birds, fish, trees, water and Native American sites but no people or any structures beyond the highway bridges we floated under.

Charles Allen canoes the Trinity River in Dallas.

Our put-in point was the Santa Fe Trestle, an old railroad bridge converted into a hike and bike trail that is the city’s first off-road trail across the river. From there, you can see the two very different sides of the Trinity. Upstream is the channelized, leveed-off section of the river that most people see as they drive past downtown on Interstate 35 and Interstate 30. Downstream is the real, natural Trinity, a glimpse into the wild. Both sides of the Trinity play a major role in the city’s plans.

Along the river, Dallas is embarking on the largest public works project it has ever undertaken, the Trinity River Corridor Project. It’s a $2 billion endeavor covering flood control, recreation, environmental restoration and transportation. The city that has long turned its back on the river is now turning toward it.

Judy Schmidt, communications manager of the corridor project, says Dallas wants to be known for more than shopping and food.

“It’s a whole different face for Dallas,” she says.

The two biggest pieces put in place so far are the Trinity River Audubon Center and the architect-designed Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge. Future plans call for a network of lakes, trails, parks, bridges and other amenities aimed at transforming the scrubby floodplain into a city showcase.

The green-built, Antoine Predock-designed Audubon Center, sitting on a reclaimed illegal dump site, serves as the city’s gateway to the Great Trinity Forest. It features hiking trails, river access, wetland ponds, forest and restored prairie and offers birding classes, kids’ activities and a monthly canoe trip. The center plays host to 25,000 schoolchildren annually for its nature-based educational programs.

“Lots of people have a negative view of the Trinity,” says Ben Jones, director of the Trinity River Audubon Center, which opened in 2008. “They don’t know it’s so beautiful.”

A 4.5-mile trail leading out from the Audubon Center is the beginning of what is to become an extensive trail system along the Trinity, with 62 miles of trails planned or in the works.

Not too far away, an equestrian center is being built. Between the Audubon Center and downtown, a chain of wetlands built on an old golf course along the river helps with flood control and provides habitat for birds and other wildlife. At the Santa Fe Trestle, our canoe put-in point, the Dallas Wave whitewater feature gives kayakers a place to play in the water.

The Trinity River in Dallas.

This summer, four major Trinity River projects are due to open, including the Trinity Skyline Trail, running along the river just west of downtown, and the Continental Avenue Bridge, a former roadway across the Trinity being turned into a place for pedestrians, cyclists and events.

On the morning of my Trinity canoe trip last fall, I stopped at Trinity Overlook Park, where a display shows the grand vision for the Trinity. The river in front of me was the one I’d always seen: walled off by levees and flanked by a few trees and some gravel service roads, with the gleaming buildings of downtown Dallas in the background. I tried to imagine the colorful scene portrayed in the display, filled with lakes, trails, parks and people. Pieces of that vision are in place.

As I got ready to leave, the morning sun peeked over the skyscrapers of downtown, leading me to think it could be a new day for Dallas and its river.

San Antonio

My family and I zipped down the hill on our bikes, with the wind in our faces, following the trail along the San Antonio River from Mission San José to Mission San Juan.

The trails had officially been open only a couple of weeks on this stretch of the river, known as the Mission Reach, but they had already been discovered. Hundreds of people were out strolling, biking, relaxing and paddling along the river on this October weekend. San Antonio was ready for this.

San Antonio’s trail meanders along the river south of downtown.

I have a son in seventh grade and a daughter in fourth grade — Texas history years in our schools — and we had gone to San Antonio to visit the four Spanish missions and the new trails connecting them. We brought the kids’ bikes with us, and my wife and I rented bikes from the B-Cycle bike share stations. The B-Cycles, introduced in several Texas cities over the past couple of years, can be used for 30 minutes at a time with no extra charge, and 30 minutes is about how long it takes to get from one mission to the next. It was history and recreation combined.

The eight miles of the Mission Reach are part of a larger, $358 million improvement effort intended to bring ecological, recreational, cultural and economic enhancements to the river as it runs through the city. More than 15 miles of pedestrian and bike paths now line the river from Brackenridge Park in the north to Mission Espada in the south.

The upper portion, the Museum Reach, opened in 2009 and connects downtown with the revitalized Pearl Brewery complex of eateries and shops. Trails, landscaping and public art create a linear park along the river. Barge rides, a popular way to see the original River Walk, are also available on the Museum Reach stretch of the river.

Many parts of the river were restored to a more natural state.

The Mission Reach, south of downtown, emphasizes ecological restoration. Native plants line the riverbanks, and the only boat traffic consists of kayaks and canoes. San Antonio has painstakingly taken steps to restore the river to its natural state after it had been straightened, widened and stripped of vegetation for flood control purposes in decades past.

Native grasses and trees are restoring the riverside woodland ecosystem and providing habitat for birds and small mammals. The enhancements also improve the “people habitat,” says TPWD’s Heger. “It’s a much nicer place with shade and vegetation.”

The river itself has been restored, too. What had been a troubled river — hot and straight, harboring only the most tolerant of fish — is now a river featuring a variety of enhancements that improve water quality, fish habitat and general river conditions. Curves have been added where possible to create a more natural river, and aquatic features have been incorporated to restore diversity, such as the addition of shallow, rock-filled riffle areas that help oxygenate the water.

“It was a good exercise in taking an urban system that’s been messed up by activities in the past,” Heger says, “and with a lot of constraints, figuring how much can we get in there and improve it.”

Paddling is now allowed on the Mission Reach, a move applauded by Alamo City kayakers and canoeists. Joe Salvador has long wanted to be able to go canoeing in his home city and was excited to finally get the chance.

“It’s nice,” says Salvador, who has taken his 4-year-old daughter canoeing there. “It used to be an ugly concrete channel.”

The Mission Reach has another purpose as well — one that ties the project to the very founding of the city. The Mission Reach reconnects the river to the historic missions that were built along it. The four missions have river-level portals along the trail to encourage visitor circulation between the river and the missions. Visitors are now biking and hiking between the missions instead of driving.

“It is a grand improvement for the town of San Antonio and will in many ways benefit the missions,” says Dan Hollifield, chief of interpretation for San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, adding that the project “is one of the finest municipal improvements I have ever seen.”

The missions don’t have official numbers on increased visitation, Hollifield says, but “anecdotally, I can tell you that it has advantaged us in wonderful ways.”

Fort Worth

In Fort Worth, hundreds of cyclists arrived on two wheels to dedicate a trailhead named after cycling advocate Arthur Cowsen.

“I was grinning from ear to ear,” says Cowsen’s son, Arthur Cowsen Jr., who as a kid accompanied his dad on a modified tandem bike in rides all over the state.

The dedication of the trailhead, in southwest Fort Worth, represented the completion of a trail extension along the Clear Fork of the Trinity River and marked another step in the city’s effort to link its neighborhoods to the Trinity. The trailhead parking lot is even in the shape of a bicycle.

Fort Worth residents are finding new ways to enjoy the Trinity.

With the Trinity River Vision master plan, Fort Worth is doing what it can to get people to embrace the river, whose forks and creeks extend through the city “like spokes of a wheel,” says Shanna Cate, programming and development manager for the Trinity River Vision Authority.

In Fort Worth, the Clear Fork of the Trinity meets the West Fork on the north side of downtown, where the original fort was built to help mark the western Texas frontier.

As in other Texas cities, the river was mostly forgotten by residents in recent years.

“You could be downtown and never know there was a river,” Cate says. “There was never really a connection.”

Fort Worth is creating new connections by building a River Walk-inspired urban waterfront neighborhood between downtown and the Stockyards, transforming 1,000-acre Gateway Park in eastern Fort Worth and adding trails, access points and other enhancements along the 88 miles of river and creek throughout the city.

To get people acquainted with the river, organizers have held a series of summer concerts at the confluence of the forks of the river downtown. In an ingenious twist, they built a stage facing the water, forcing people to get in inner tubes in order to get the best seats. The concerts draw hundreds of people with live music and the novelty of tubing the Trinity.

In spring and summer months, kayaks, canoes and paddleboards are available for rental.

The centerpiece of the Trinity River Vision project is Panther Island, a canal-lined urban neighborhood being created with a 1.5-mile river bypass channel.

Another major component is the reworking of Gateway Park along the Trinity east of downtown. Plans call for 15 miles of new trails, a mountain bike course, sports fields, canoe/kayak chutes and 80,000 new trees.

The third part of the vision is enhancement of the 70 miles of trails along the city’s rivers and creeks. Organizers are tackling 90 user-requested projects on the trails, including trail extensions, parking areas, bridges and water fountains.

Fort Worth residents have been discovering and using the trails in ever-growing numbers.

“If you go down there on a Saturday, there are hundreds of people,” Cowsen says. “There’s no lack of people running, rollerblading, cycling.”

Cowsen welcomed a new addition to the family last year — Arthur Cowsen III. He can’t wait to get him out on

the trails.

Houston

It used to be called the Reeking Regatta. The annual canoe race down Houston’s Buffalo Bayou, today one of the state’s biggest canoe/kayak races and since renamed the Buffalo Bayou Regatta, was billed as the world’s smelliest canoe race. That’s changed now. The bayou has come a long way.

“The time is right to start making full recreational use of our bayou system on a regular basis,” said a Houston Chronicle editorial before this year’s event in March.

The Buffalo Bayou Partnership is in the middle of a 20-year master plan to revitalize the bayou. It’s working on doubling the trail mileage along the bayou, renovating parks and reclaiming the spot where Houston was founded, all with the aim of deepening the connection between residents and the bayou.

Joggers and cyclists make use of a revitalized Buffalo Bayou in Houston.

“Houston is seeing incredible development, and we’re seeing more and more young people access the bayou,” says Anne Olson, president of the partnership. “These kind of open spaces are going to be more and more important. We realize that quality-of-life amenities matter.”

In the past several years, the city has added trails, built pedestrian bridges over the bayou and reclaimed space under highways to make the bayou more of a recreational destination.

Houston is also working on connecting 150 miles of trails along bayous and creeks.

West of downtown, 160-acre Buffalo Bayou Park is undergoing a $58 million renovation. Organizers are adding trails, planting 15,000 trees, installing an 11-acre native prairie, building a nature playground, constructing footbridges and restoring bends along two miles of the bayou.

“It will be a major attraction,” Olson says.

Downtown, the partnership is restoring a historic building and grounds at Allen’s Landing, where the city was founded, and will offer canoe, kayak and bike rentals there.

The award-winning Sabine Promenade near downtown transformed an area under Interstate 45. The project added native landscaping, put in canoe launches and installed 12 street-to-bayou connections, each with public art entryways.

“It has won a lot of awards. It shows people what they can do in a very urban area in a very difficult stretch,” Olson says. “It’s all under existing freeways.”

A TPWD paddling trail covers a 26-mile stretch of the bayou, and new canoe/kayak launches are being added at points along the way.

The Bayou City is living up to its name.

» Like this story? If you enjoy reading articles like this, subscribe to Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine.

Related stories

For more on water, check out TPWD's State of Water, with water-related videos, magazine articles and other resources.