Purple Martin Majesty

Unlocking the secrets of a songbird’s amazing journey.

By Elaine Robbins

The air is filled with a sweet chirruping as purple martins wheel and glide in the sky above a complex of birdhouses set on the gently rolling brushland property northwest of Corpus Christi. Other martins skim a nearby pond for insects or perch on the front stoops of their houses, gossiping with their neighbors.

At a long table, a team works quickly to tag one of the birds. Canadian biologist Kevin Fraser takes measurements, extracts blood for DNA samples, then snips feather samples for isotope studies before handing the bird to a volunteer to set it free.

While the team works, other purple martins waiting to be tagged hang in individual cloth bags pinned to a clothesline — a fitting image for a species so accustomed to humans that it has been called “America’s backyard bird.”

The work is part of a unique collaboration between scientists and volunteers tracking the migration of North America’s largest swallow from Texas to the tropics and back. Songbirds are in decline worldwide, so scientists are examining their migration routes. Purple martins, although thriving in Texas, are disappearing from their northern breeding grounds in places like New York, Pennsylvania and Ontario.

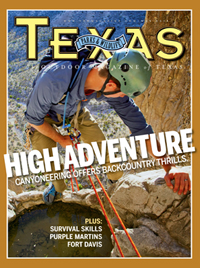

Purple martins depend on humans to provide lodging such as this martin house at a property in the Hill Country.

Since songbirds — which weigh less than 2 ounces — obviously can’t be radio-collared like mountain lions, it was a challenge to develop something lightweight that wouldn’t interfere with their behavior.

The breakthrough came in 2007, when Bridget Stutchbury, lead researcher at York University in Toronto, used miniature geolocators placed in tiny backpacks tied around the birds’ hips to “tag” 20 purple martins and 14 wood thrushes from a colony in Edinboro, Pa. The next year, when two of the birds returned from South America, the tiny computers on their backs revealed their location every day of the yearlong journey.

“We now had the world’s first detailed records of the long-distance migration of small songbirds,” Stutchbury wrote in the journal Science. The research was hailed as a breakthrough in The New York Times and National Geographic.

Stutchbury, however, was concerned that the project still had a major flaw. In the first two years of tagging, only five of the 40 birds fitted with geolocators had returned — far short of the 40 to 50 percent return rate achieved in songbird banding studies. Were the geolocators somehow hurting the birds, she wondered? Were the light sensors that protruded from their backpacks attracting predators or interfering with the birds’ normal activities?

She also wondered if purple martins from the southern United States would fare better than Pennsylvania birds because they had less distance to travel to the tropics. To test this theory, she approached Louise Chambers, editor of the Purple Martin Conservation Association newsletter, and Chambers’ husband, John Barrow, a lawyer and judge. The couple had a thriving purple martin colony in their backyard in Corpus Christi, and they agreed to participate, along with Jeff Webster, who managed another colony a few miles away. In the spring of 2009, new lightweight geolocators with shorter light sensors were deployed on 20 birds from the two Texas colonies.

Take Me Back to Texas

The following winter was cold and rainy, and by early February 2010, only 10 purple martins had returned to Chambers and Barrow’s backyard. Few insects were flying in the bad weather, so the couple shoveled thawed-out frozen crickets and mealworms onto a supplemental feeder and waited. Finally, on Feb. 11, Chambers glanced out the window of her home office, which looks out over their colony, and spotted on the feeder what they’d been waiting for: a female with the light sensor sticking up through her feathers like a grain of rice.

John Barrow maintains a purple martin colony at his Corpus Christi home. He participated in a study in which purple martins from the colony were outfitted with geolocator devices to track their migration movements from Texas to South America.

Chambers called her husband at work, and he jumped on the phone and assembled a team of volunteers. They arrived at the house an hour later, excited but nervous.

“If you lose the bird, you lose the geo,” Barrow says.

As they strained to keep their eyes on the prize, the female hopped from gourd to gourd.

“A male was trying to get her to make up her mind and come in with him, but she wanted the other compartment,” Barrow says.

Just before dark, a norther blew in, bringing rain and plunging temps. The team stood in the cold and watched until finally the female went into a gourd with the male. Moving quickly, they climbed up and plugged the cavity’s hole.

Early the next morning, they retrieved their quarry. First they pulled the male out of the gourd and released him. Then they carefully carried the female inside into the bathroom — where if she escaped she couldn’t go far — and pulled off the geolocator. Barrow still remembers how he felt the moment they retrieved their first geo.

“You’re holding a little device that’s traveled 5,000 miles on the back of a bird for eight or nine months,” he says. “It’s an awesome feeling — it’s almost unbelievable.”

But his exhilaration was short-lived. After the capture of the martin, they didn’t see another tagged bird for five long weeks.

Finally, in late March, their luck changed. On March 23, Webster spotted the first tagged bird at his colony. Holding a large plastic cup taped to a 10-foot pole over the entrance, he managed to trap the bird in a gourd. But with no hands free to lower the rope-and-pulley complex and retrieve the bird, he had to use his cellphone to call for help. Chambers jumped in her car and raced over, and soon the pair had retrieved the second Texas geolocator.

In the weeks that followed, more birds returned, and by April 19, the Texas team was able to declare a victory. They had captured nine out of 20 birds fitted with geolocators — and had found three more birds that had lost their geos.

“Texas is the second location in North America where geolocators were put on purple martins,” Chambers says, “and Texas was the first to see the desired return rate of 50 percent of the marked birds.”

A few weeks later, the Pennsylvania team retrieved 11 out of 21 of their geos.

“We knew that we had solved the problem,” says Stutchbury, “and we could proceed without wondering if we were hurting the birds.”

Discovering Migration Secrets

The research brought discoveries that challenged ornithologists’ assumptions about purple martin migration. Until then, scientists assumed that the birds’ decline was due to pesticide exposure in their wintering grounds in the soybean and sugarcane fields of southern Brazil.

But Stutchbury was surprised to find that the tagged birds didn’t even go to southern Brazil. Instead, they wintered deep in the Amazon rainforest, where “America’s backyard bird” showed its wild side by sharing the jungle canopy with green Amazon parrots and red howler monkeys.

“It’s kind of heartening to know that one last great wild place on the planet is full of purple martins,” she says. “It makes me feel really good about their long-term future.”

Another surprise was how fast the birds flew. The tagged purple martins traveled 250 to 300 miles per day in the first leg of fall migration and flew even faster coming back from Mexico in the spring. One returned from the Amazon region of Brazil in just over two weeks. That’s a breathtaking 360 miles per day — four times faster than the 90 miles a day estimated for other songbird species.

The pacing of the birds’ journey also challenged scientists’ notions. The tagged martins flew incredibly fast to Mexico in what Stutchbury calls a “slingshot migration” and then did something unexpected: they stopped for an extended vacation in the Yucatán, or sometimes in Central America, before continuing their journey south.

“Why go that fast for two or three days and then stop for two or three weeks?” asks Stutchbury. “We used to think these birds migrated like we drive cars. You fill up the tank, and you drive on until you get low on gas, then you stop and refill, and maybe have lunch and keep going. It makes us rethink everything we know about songbird migration.”

Purple martin with geolocator.

Since completing the groundbreaking work in Pennsylvania and Texas, Stutchbury and Fraser have tagged martins in a dozen locales across the United States and Canada. They now suspect that climate change is a major culprit in the birds’ decline, and their latest research focuses on whether the birds can adapt. The spring of 2012 was the hottest on record, but purple martins did not adjust their arrival time in North America, as some shorter-distance migrants do.

“This means they arrived ‘late’ for the advanced spring,” Fraser says, “and likely missed out on peak food they need to be productive breeders.”

In the face of dramatic climatic changes in their northern breeding grounds, will America’s backyard bird survive? Stutchbury thinks they will fare better than some other species.

One reason is that, although they are declining in the northeastern U.S. and Canada, their populations are thriving in Texas and the South. Another is that purple martins possess an uncanny ability to attract human helpers, or “landlords,” to provide free housing, protection from predators and even supplemental feedings in cold weather.

“They’re personable birds,” Barrow says. “People fall in love with them.”

And finally, their winter grounds deep in the Amazon rainforest ensure their protection for years to come.

Fraser theorizes that the “early birds” — the first arrivals up north in the spring — may hold the key to the species’ survival as the changing climate brings an earlier spring. If martin landlords can support these early arrivals and help them to be productive breeders, it may ensure that their DNA is passed on to help the species adapt. If all goes well, these aerial acrobats will continue to return to our backyards each spring, filling the air with their sweet song.

A New Tracking ToolThe device used to track purple martins is a miniature version of a geolocator developed by engineers at the British Antarctic Survey to track albatrosses. It consists of a light sensor, a clock, a battery and a microprocessor. The light sensor records sunrise and sunset times for each day of the bird’s journey. Sunrise times indicate a bird’s longitude. Since days are long in summer and short in winter in the northern climes, day length on a given date reveals latitude. Unlike satellite transmitters, geolocators don’t provide real-time tracking. Data can be read only when — and if — the tagged bird returns with the device on its back. Since songbirds are too small to carry radio transmitters, as eagles and falcons have, biologists have been limited to banding them or watching mass migrations on weather radar. This groundbreaking research paved the way for dozens of other songbird studies. Researchers have since discovered migration secrets of the black swift and red knot, the Pacific gold plover and the Arctic tern. Many more studies are currently underway. |

The female purple martin known to researchers as 511M spent the spring in a backyard in Corpus Christi, then started her migration south in late June after her nestlings fledged. Soaring at breakneck speed down the Texas coast and probably overland around the Gulf (since only one reading per day is recorded, this part of the route is inferred), she reached Oaxaca on Mexico’s Pacific Coast a day later. Then she doubled back to the Yucatán, where she made an extended stopover for the whole month of July. On Aug. 3 she continued south, traveling through Central and South America and arriving two weeks later in the Amazon basin in northern Brazil. There, 511M spent five months in the Amazon rainforest before making her way back to her breeding colony in Corpus Christi.

Related stories

Wild Thing: Purple People Lovers

Spring/Summer 2014 Birding Calendar