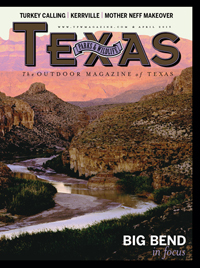

Wild as a River

Bob Burleson’s adventurous spirit led him to enjoy and conserve the natural world.

By John Jefferson

As a kid, Bob Burleson dreamed of becoming a mountain man. His dream came true, but he became much more than that. Burleson was a true Renaissance man, a person knowledgeable and skilled in numerous disciplines.

In Burleson’s case, those disciplines included law (his chosen profession), archeology, botany, natural science, conservation, exploration, hunting, ecology, canoeing and caving. He also was adept at plumbing, electrical wiring, oil field work, farming and automotive engine repair.

“He knew more about more things than anybody I’ve ever known. He was my Wikipedia!” says his brother, Bruce, a lawyer for Scott and White Hospital and an ordained minister who helped officiate Burleson’s memorial service in 2009.

Through observation and diligent practice, Burleson learned to play (by ear) the guitar, mandolin and banjo and even speak Spanish. His guidebook, Backcountry Mexico (University of Texas Press, 1986, co-authored with TPWD’s David Riskind), included an extended glossary of Spanish phrases.

Burleson and his guitar were frequently found around riverbank campfires. That guitar accompanied him on countless trips down the Rio Grande and other streams. Wife Mickey says her husband, blessed with a photographic memory, knew all the verses to thousands of songs. Linda Aaker, wife of former Texas Parks and Wildlife Commissioner Bob Armstrong, recalls that Burleson sang all 18 verses of Rosalie’s Good Eats Café at their annual ranch campfire.

He hiked many mountains, but he also spent a great deal of time arguing courtroom cases, testifying before congressional committees, floating rivers, teaching Sunday school and influencing Texans and others about the need to conserve precious and fragile natural resources. He once gave U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas a guided tour through the Lower Canyons of the Rio Grande.

The Burlesons made their home on a 500-acre reclaimed cotton field northeast of Temple that they restored to nearly its original state as a native tallgrass prairie. Today it boasts around 100 species of wildflowers and other native plants that didn’t exist on the cotton field. The Burlesons shared their slice of paradise with many people through tours and field days.

Burleson and wife Mickey on a relaxed float trip.

Mickey Burleson still lives there. Sitting on the couch listening to her tell stories about Bob, I notice the unusual fireplace. Many of the limestone blocks around it bear reproductions of Native American rock art.

Of course, archeology was one of Burleson’s avocations, and Mickey partnered in many of his explorations. He led archeological surveys in many areas, including around Lake Belton and on (what was to become) Stillhouse Hollow Reservoir. His disdain for artifact plundering led him to draft and assist in passing the Texas Antiquities Code. Burleson participated in numerous Texas Archaeological Society field schools, enlivening their evenings by leading the music.

The Burlesons’ library is a long set of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, extending about 30 feet down a hallway. Mickey said Bob had read every volume, some more than once. He despised television, preferring instead to read.

Burleson was greatly respected as a trial lawyer, practicing in Temple and primarily defending medical malpractice suits. He had several offers to move to larger firms in Dallas and Houston, but he politely declined each one.

“I don’t want to work more than five minutes away from open country,” he told his wife. It’s a sentiment reminiscent of conservation icon Aldo Leopold’s quote in Sand County Almanac: “There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot.” Burleson and Leopold certainly fit the latter description.

Burleson was interested in all wildlife, and particularly fond of birds. Mickey said he could identify most species on the wing. Yet he loved hunting doves and quail — not unlike John J. Audubon, who shot birds to study them up-close for his famous and enduring paintings.

During the 1970s, as interest in canoeing Texas rivers burgeoned, Burleson’s name was spoken with reverence around streamside campfires. He had canoed all the canyons of the Rio Grande and compiled field notes that most considered a “bible” of work. The National Park Service still uses some of his observations.

Burleson along the Rio Grande.

He urged protection for the Rio Grande and worked tirelessly for its designation as a Wild and Scenic River, both in Washington and on the river itself. A Texas Observer article by Dave Richards tells of Burleson, Armstrong, Richards and others taking a New York Times journalist down the river to gain support. The columnist subsequently wrote that it mattered not what Congress did: The river and the people were already wild enough.

Burleson went on to become executive director of the American Whitewater Affiliation, the national association of whitewater river runners.

The Burlesons hiked extensively. Often, it was more than just a walk in the park. On a hike to the Guadalupe Mountains, Mickey said rattlesnakes were everywhere. They wore snake leggings, and stayed on high alert. Except once. Stopping to rest, Bob started to sit down on a big rock, but abruptly changed his plans when a rattler sounded beneath him.

Mickey recalls another time when Bob got stuck exploring a small cave. His pistol holster hung up on the tight rocks as he was crawling out backward. Unable to go forward or backward, he was trapped underground. He finally managed to twist the holster around to his back and wriggle out.

The Burlesons met Riskind in the Guadalupe Mountains and became lifelong friends and fellow adventurers. Together, they paddled the rivers and explored the boondocks.

Riskind says that Burleson’s knowledge and passion for West Texas led him to contact the Texas land commissioner and discuss initiating a natural area survey of state land, a significant turning point for Texas state parks. Through that survey, and with the help of the Texas Explorers Club (which Burleson helped form), the Guadalupe Mountains were designated as a national park. Other survey sites that became state parks or natural areas include Big Bend Ranch, Devils River, Enchanted Rock, Hueco Tanks, Lost Maples, Seminole Canyon and others.

Burleson’s experience and dedication to wilderness areas led to his appointment to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission in 1968. He became a strong voice for conservation but riled some by opposing dredging of oyster beds, which damaged marine life. His term expired in 1975. Mickey also served on the TPW Commission from 1993 to 1999.

One so knowledgeable on so many subjects could easily become a stuffy, insensitive egotist, but that was definitely not Burleson. In an article written by Lea Burleson Buffington about her father, Riskind is quoted as saying that Mexicans would describe Bob as simpatico. Said Riskind, “It connotes that he is one of us.”

The minister of the small church the Burlesons attended (and helped with mission trips into Mexico) wrote an admiring, posthumous blog about Burleson called “Who Taught You How to Live?” The clergyman even named his son Bob.

Bob Burleson’s warm smile told everyone he met that he was genuinely interested in what they had to say. He was a student of life, learning something new from everyone he met, from everything he did and from every bend in the river.