Bat Mania

Pest-eating flyers face an uncertain future.

By Amy Price

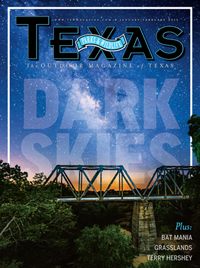

Most of us have seen bats silhouetted against night skies over backyards and fields, winging through the “Friday night lights” of football stadiums, etched in moonlight during a meteor shower over Palo Duro Canyon State Park or steadily climbing like smoke during a sunset emergence. Though we may recognize the iconic dips and spins of bats in flight, much of the magic of bats is a mystery to even the biggest fans of Texas wildlife.

Every Texan lives near bats. Some of Texas’ 33 bat species prefer limestone regions with caves, sinkholes, streams and large springs. Others are found in forests, and many call highway bridges home. There are bats roosting and foraging across the plains and in the canyonlands. Crops, forests and orchards — as well as native plants across the state — benefit from the pest management provided by bats.

Bracken Cave.

Bats are one of the most ecologically and economically important wildlife species worldwide, but also one of the most threatened. In the United States, almost half of the 47 bat species are listed as endangered, threatened or sensitive at a federal or state level. In Texas, 23 bat species are listed as “species of greatest conservation need” in the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Texas Conservation Action Plan.

Partnerships between TPWD and Bat Conservation International prevent further bat species extinctions and help identify and protect significant bat areas to ensure lasting survival of the world’s 1,300-plus bat species.

Let’s take a closer look at four bat species on the list.

Mexican free-tailed bat

The Mexican free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis) is the official flying mammal of Texas. These bats are small and soft, with chocolate-colored fur and long, narrow wings. Their wrinkled faces, pug noses and big, round ears make them some of the most personable bats in the state. They are adept at high, fast flight — flying so high that Randolph Air Force Base near San Antonio developed a bat avoidance program.

Some 100 million Mexican free-tailed bats migrate to Texas in March and April, forming summer colonies to birth and rear pups (one per female). Bracken Cave in Comal County containsthe world’s largest bat colony; 10 million to15 million bats return to this maternity roost annually. The limestone walls of this bat nursery are crowded, with hundreds of pups in each square foot. Mothers find their pups by remembering the approximate location, then recognizing the pup’s unique voice and scent.

Bat Conservation International owns and protects the cave. The bats of Bracken eat more than 140 tons of insects each night, saving farmers millions of dollars in reduced crop damage and lower pesticide use. Mexican free-tailed bats consume the worst pests of cotton, corn, pecan and grape crops.

|

Mexican long-nosed bat

The Mexican long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris nivalis) is the only federally endangered bat in Texas. This nectar-feeding species migrates north every spring following the blooms of agaves, so protecting the agave corridor is critical for the survival of the species. Wild agave populations are not extensive, limited to specific mountaintops and routinely harvested in Mexico for reasons including mescal production. Any activity that disrupts these “agave islands” creates a burden for female bats attempting to complete northward migrations into Texas during pregnancy or with young born in Mexico during April, May and early June.

The first discovery of this species in the United States was in 1937 at Big Bend National Park, where the Chisos Mountains are home to the only known cave roosts of Mexican long-nosed bats in Texas. The bats have long, nectar-lapping tongues that can extend several inches deep into flowers. Their faces are characterized by a long muzzle with a prominent nose leaf at the tip.

Nectarivorous species like these have broad wings with long tips, allowing them to hover at the face of the flower. This bat, with its elongated, furry face, is often photographed with a bright dusting of pollen across its head and shoulders.

Currently, the National Park Service and Bat Conservation International are funding research from Texas A&M University to create a detailed model for habitat needs and migratory patterns of the Mexican long-nosed bat.

|

Pallid bat

Pallid bats (Antrozous pallidus) are terrestrial insect eaters. They can land on the ground and hunt large prey such as centipedes, scorpions, beetles, praying mantises and crickets. They are considered one of the strongest predators among insectivorous bats — even the venom of scorpions seems to have no effect on them. Pallid bats often take their prey to a night feeding perch, creating middens of discarded insect parts. The feeding habits of pallid bats tend to result in injury to the bats, so it isn’t uncommon for researchers in the field to capture bats with significantly torn wings, broken bones and injuries from cactus spines. This species has documented healing from substantial wounds, making it a favorite bat among wildlife biologists for its sheer toughness.

With big ears half as long as their bodies, pallid bats are able to hear their prey walking, without any use of echolocation. This “passive sound localization” is so refined that from almost 20 feet away, a pallid bat can land within two inches of insect prey after hearing a single footfall.

These bats are found in canyonlands and arid regions, roosting in rocky crevices. Pallid bats have pale yellow-brown and cream-white fur to best blend in to rocky landscapes. Pups, usually twins, are born in May and June. Colonies of this bat are frequently small (fewer than 20 bats); many roost individually.

|

Rafinesque's big-eared bat

Rafinesque’s big-eared bats (Corynorhinus rafinesquii) are nicknamed “whisper bats” because they have a low-amplitude echolocation call that is difficult for scientists to record with bat detectors. These bats are easily recognized by their very large ears that curl and move and become almost translucent in strong light. Rafinesque’s fur is longer than many other bat species in Texas, giving them a softer, shaggier appearance. Unlike many insectivorous bats that “hawk” only flying insects, this species is capable of gleaning pests from the stalks and leaves of plants.

Rafinesque’s big-eared bats roost in the hollow cavities of mature, old-growth trees in hardwood bottomland forests in Texas.

“One of the most exciting things I’ve experienced as a bat biologist is crawling into a hollow tree in a swamp, and looking up into the cavity to see dozens of beautiful Rafinesque’s bats staring down at me,” says Bat Conservation International’s Mylea Bayless, who did much of her field work with this species. “It is so thrilling. I can tell you that it makes you want to go look in every hollow tree from that point on in your life.”

As their habitat disappears, these bats have utilized abandoned buildings and other structures, but even these roosts are disappearing rapidly as buildings deteriorate or are removed for safety concerns. Texas is one of a handful of states experimenting with artificial roosts designs specifically for Rafinesque’s big-eared bats. In the Trinity River National Wildlife Refuge, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service funds the preservation of an abandoned house that the bats favor as a roost. The refuge’s artificial roosts are becoming popular with the bats as well and will provide options when the house is beyond repair.

Unlike the Mexican free-tailed bats or Mexican long-nosed bats, this species is considered “sedentary” because it doesn’t migrate and may move only a few kilometers between roosts. The species has high “site fidelity,” which means the bats prefer to use the same roosts year after year. At intervals during a Texas winter, these bats goes into a torpor, a special behavior, in which they lower their body temperature to save energy.

|

» Like this story? If you enjoy reading articles like this, subscribe to Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine.