The Art of Nature

Orville Rice’s paintings of wild things helped define an era of TP&W magazine.

By David Baxter

Orville Rice’s iconic artwork graced covers of Texas Game and Fish for a decade (1945-1955) and helped establish this publication’s wildlife graphic arts reputation and tradition.

Rice was in his mid-20s when he started selling art to the magazine in the post-war years for about $25 a piece. Even as a young man he was already well on his way to becoming a skilled wildlife artist and naturalist. Texas Game and Fish was but one of the stops along the trajectory of his life.

Born in the coastal prairie town of Yoakum in 1919, Rice grew up in a rural setting where wildlife, especially birds, could be observed on the short walk to a pond behind his family’s farmhouse. He was not a rock-chunking kind of kid, oblivious to his natural surroundings, as shown in this excerpt from his 1934 journal at about age 15:

“On a walk around Preutz’s Lake, I came to a willow tree that had fallen into the water,” Rice writes. “Roots were sprouting out along the underside of the trunk and branches, making a well-hidden little puddle in the center. It was when I was passing by this particular spot that something inside me seemed to say, ‘Look around — at the roots.’ Maybe it was instinct, or perhaps out of the corner of my eye I saw some motion there. … Presently I saw a short fat bird with a striped belly and short tail. The bill was small and the nostrils were connected by a hole through the bill. … It certainly was a queer looking little bird. It was a sora, or sora rail. Two days it was there, sneaking about in the shallow water, and then it just disappeared. I suppose that it was travelling and just stopped for a short rest.”

That same year, Rice entered a contest sponsored by the Cuero Turkey Trot and the Cuero Business and Professional Women’s Club. His entry, “Birds That May Be Seen Around Yoakum,” was a compendium of 50 watercolors illustrating the local birds and won First Premium prize. It and thousands of other such memories are still part of his family’s collections, treasured even more since the artist’s passing in 1986.

Dinah Chancellor, one of Rice’s two daughters, has the blue-ribbon Turkey Trot entry.

“Daddy was a curious child,” Chancellor recalls. “He did more than just superficially identify birds; he wanted to know how they survived and how things fit together in the natural world.”

His other daughter, Kathy Parsons, echoes that sentiment.

“Dad was always wandering off into the woods as a little boy and collecting birds,” she says. “That continued as an adult. When Dinah and I were growing up [in Topeka, Kansas] he used to drive our mother crazy with the dead birds and other specimens that he kept in an extra freezer. His friends also would send him carcasses to draw from.”

His daughters say Rice went to great effort to get the details correct.

“I recall him climbing up a tree to get a better look at a nest that contained two cardinal eggs and two of a cowbird,” Parsons recalls. “He shinnied up the tree regularly to see how the birds were doing. Much of this detail is reflected in his paintings. They are artistically appealing but also true to the natural world.”

As a youngster, before he had a camera, Rice made pencil sketches in the field of those details that he later used to finish his painting, she says.

Rice left Yoakum for the University of Texas in Austin, where he studied architecture rather than art. His practical parents encouraged this, as they felt he could make a better living as an architect than as an artist.

While at the university, Rice fell ill with a lung ailment first thought to be tuberculosis but later diagnosed as histoplasmosis, which develops from a fungal spore found in the droppings of birds and bats. One of his professors found a sanatorium for him in the Davis Mountains of far West Texas, where Rice spent a year recuperating.

For a naturalist, albeit an ill one, the Davis Mountains are a good place to recover. Instead of giving in to the isolation and depression accompanying a severe infection, as others might, Rice turned his mind to learning all he could about the natural surroundings.

“I can never remember him being anything but optimistic, mentally active and curious,” says Parsons. “When my sister or I attempted to mope or feel sorry for ourselves, he would say ‘Pobrecita!’ and wind up with us laughing about it.”

Despite his parents’ practical advice, there were few architecture jobs for young Orville when he graduated from UT and married Zora Wilkerson in 1943. Moving to Wichita, Kansas, he took a job at the Boeing Aircraft Company as a draftsman. His employers soon discovered his talents and used his art to illustrate flight manuals and employee newsletters, complete with cartoons of folks working on planes.

Rice finally put his architecture degree to use, working some 33 years in Topeka, designing structures all over Kansas, including Topeka’s First Baptist Church, where he taught adult Sunday School. Throughout his life, Rice painted images of wildlife, providing illustrations for books and for magazines such as this one. He retired from architecture in 1981 to devote more time to birding, photography and painting. Rice went on to illustrate numerous books and issues of Cornell University’s ornithology journal, win first place in the Kansas Wildlife Art competition and have paintings exhibited in National Audubon Society shows.

Rice often incorporated his own image in paintings and exhibited a playful side that sometimes went unnoticed by subscribers to Texas Game and Fish. Take a close look at the big-horned owl painting in a spooky Halloween setting that he did for the November 1947 issue. Can you find the witch riding a broomstick? No subscribers at the time did, and it took some searching on my part after Dinah Chancellor told me about it.

In addition to painting, Rice read and appreciated the whimsy of James Thurber and Dr. Seuss. Here’s a sampling of his own verse:

Ode to the Ota

I don’t think I’ve ever seen an ota –

Not even a glimpse as big as a tiny iota,

But if I wanted to take a colorful photo

Of a fancy ota propelled by a motor,

Perhaps I’d aim at an antique DeSota

Or toy a little with a little Toyota!

— O. Rice, Jan. 1984

That humor would go a long way in helping his family cope with the artist’s penchant for filling the freezer with feathers or accumulating cages of injured or orphaned birds. Rice served as the president of the Topeka Audubon Society for many years, and its members often would bring him injured birds, which he kept in cages in the living room, splinting broken legs with Popsicle sticks.

“One year our cat killed a Bewick’s wren,” Parsons remembers. “We took over the entire garage, and Dad and I fed her babies mealworms on the floor until they were old enough to feed themselves. Then we got down on our hands and knees out in the yard to teach them how to catch their own bugs.”

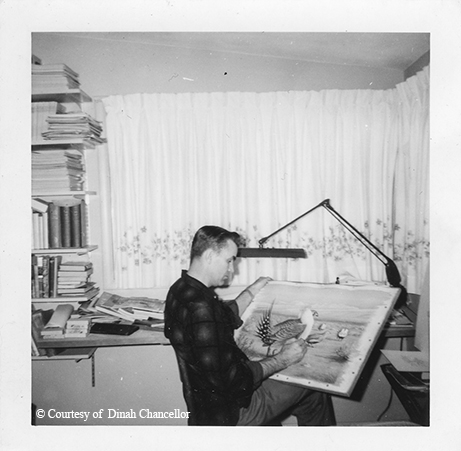

Both Chancellor and Parsons have memories of going into their dad’s studio, which was in his bedroom, watching him paint, sometimes discussing things with him, but often just quietly watching their father work.

“Daddy was a teacher of the first order,” Chancellor says. “He wanted to share his love of the natural world with his daughters and anyone who showed an interest. My husband, Ray, learned how to do watercolors by watching Dad.”

Rice took his daughters and others on bird counts, teaching them how to look at flight patterns, bill shape and other field characteristics. He may not have had students in a formal classroom, but he was eager to share with everyone, giving countless presentations to schools or civic groups on wildlife or architecture.

Orville Rice died in 1986 at the age of 66, but his legacy endures. John Jefferson, a longtime popular contributor to this magazine, is a big Rice fan.

“My grandmother gave me a subscription to the magazine [Texas Game and Fish] when I was about 7,” he says. “I received the first issue, and many more thereafter. I think she was afraid that I was growing up fatherless without a man in the house to teach me about the ways of the woods and waters, so she sent me a subscription for years.”

Jefferson, who led TPWD communications from 1975 to 1978, watched the transformation of the magazine and Rice’s work.

“I would stare at Orville Rice’s covers, and dream of the fishing and hunting scenes his paintings depicted,” Jefferson says. “There was a big war going on, and gas and tires were rationed. My mother didn’t take any unnecessary trips, and going to the woods wasn’t a priority until the war and rationing ended. The magazines with Rice’s covers were about all I had, besides the woods behind our house.”

Jefferson was thrilled to be able to use Rice’s work recently on the cover of the Outdoor Annual, TPWD’s handbook of hunting and fishing regulations.

“I dream those same childhood dreams each year when we run one of Rice’s paintings on the cover of the Outdoor Annual,” he says. “When it was decided to use them, I felt like it was a homecoming, of sorts, for me.”

Rice’s bighorn sheep is on the cover of the 2016-17 Outdoor Annual, as well as on the cover of this issue.

David Baxter was editor of Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine from 1977 to 1998. |