Making Waves

Competing in Cedar Hill's open-water contest is no lazy lap at the pool.

By Lisa Roe

Les Mejia is ready. After only three months of training, the stay-at-home grandmother stares intently at the inflatable yellow and red buoys floating in Joe Pool Lake, memorizing the course for the 750-meter swim race. This will be her first race in nearly 40 years. She looks calmer than she feels.

“I’m excited, but I just want to be in the water now,” Mejia says. “The waiting is driving me crazy.”

In a sense, she’s been waiting for this race, the Open Water Swim Challenge and Aquathlon at Cedar Hill State Park, since her days on her high school swim team.

On this July day, she is finally competing again — and she isn’t taking baby steps.

Mejia has set herself an epic challenge: becoming a triathlete at age 55. She chose the two-sport swim/run aquathlon to ramp up her training for the three-sport competition, which adds cycling. Even more challenging, she will be swimming for the first time in open water — in one of Texas’ famously murky lakes.

Wading into open water

Open-water swimming is night-and-day different from racing in a pool. There are no crisp blue lines or floating ropes to keep you on track, no sparkling clear water that lets you see where you’re headed. You have no idea how deep the water is — and you're definitely not swimming alone.

Splashing, kicking feet and arcing arms pose problems in open water. You have to keep popping your head out of the water to figure out if you’re headed in the right direction, and when your head is in the water, all you see is green.

It’s no wonder panic can set in.

“People get afraid and anxious when they can’t see anything,” says race director Frank Cortese of Tri-Now Endurance of Dallas, which provides multi-sport coaching as well as event production. “They get panicky, and their breathing picks up, their heart rate picks up. That creates a vicious cycle because they’re not able to breathe effectively, which is very important in swimming, to have that rhythmic breathing going.”

As a coach, he helps swimmers learn to take time to be present.

“I’ll have athletes stand on the shore and look around,” Cortese says. “I’ll say, ‘Report back to me what you see.’ They’ll say, ‘I see water.’ Good. ‘I see land.’ Good. I’ll just get them to check in, and that’s what helps them.”

For a lot of people, the added challenge of open water just makes it more fun.

Why do it?

Having fun and getting exercise is all the challenge some racers seek. Some are motivated by health problems; others are there to train for triathlons. Some are clearly “in it to win it.”

Triathlete Shannon Small of Houston is here to start rebuilding her swimming and running distances after a couple of surgeries made cycling painful. Her challenge is getting her body back to where she used to be. Her doctor’s challenge is getting her to slow down a little during recovery.

“I was like, ‘No, what if I slow down and I can’t speed back up?’” she says. “I’m always thinking, ‘But what about tomorrow?’ You just don’t know what’s going to happen.”

For retired engineer Brian Cavern, the challenge is to keep doing what he loves as he ages. Now 74, Cavern has been competing in triathlons for 18 years, and he still tries to do five or six a year. He gets in some open-water swim training at Purtis Creek and Tyler state parks, and he’s at Cedar Hill to focus on his swimming distance as part of a training regimen. He asks himself if he should still compete. Last year he decided he’d done enough.

“But all I really needed was a break over the winter,” Cavern says. “I didn’t need to quit. I was just tired from the season.”

And Mejia? After a lifetime taking care of her family, this is about doing something just for herself.

“This has been a dream for a long time,” Mejia says. “This is something for me, something just for me. Finally, I’m here and I can’t believe it. It’s just a dream come true.”

First-time challengers

The Cedar Hill aquathlon is tailor-made for customizing. The standard aquathlon short course is a 750-meter swim plus a 5-kilometer run. The long course is a 1,500-meter swim followed by a 10-kilometer run, basically doubling the sprint distance. Racers there just to swim can choose from three lengths: 750 meters, 1,500 meters or 4 kilometers. The multiple distance options are particularly helpful for first-timers.

Also helpful is the event’s relaxed, friendly feel, with a supportive environment and a coordinated safety net. Dallas outfitter Kayak Power provides eight kayaks, staffed with certified lifeguards around the course. Members of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary are on personal watercraft, ready to spring into action to help struggling racers.

Holding the event at the state park was a first for Cortese and Tri-Now. Only 20 miles from downtown Dallas, the park offers a peaceful natural area that’s easy to reach for Metroplex residents. There’s a lot to do at Cedar Hill. Its 7,500-acre Joe Pool Lake is great for black bass, crappie and catfish fishing, as well as boating, paddling and swimming. The Penn Farm Agricultural History Center highlights how farming has changed over time. Mountain bikers and hikers can enjoy the DORBA Trail, named for the Dallas Off Road Biking Association, whose volunteers built the trail. For future racers, 350 developed campsites will cut the journey to the starting line to mere minutes.

The site worked so well that Tri-Now will be holding its next aquathlon on July 29 at the park, and its first Cedar Hill Triathlon was held June 10.

It's on!

During Cortese’s pre-race instructions, he asks for a show of hands from people who had done an aquathlon. Very few hands go up. That experience level, combined with the many course options, means he’ll give an in-depth rundown of which yellow triangle buoys and red “tomato” buoys to shoot for — and how many times to swim around them for each race length. The run is easier to explain: Make one loop for the shorter distance; do two for the longer. Chips inside bands around the racers’ ankles document their times.

As it gets closer to the 7:30 a.m. start time, racers gather in the corral, a roped-off area where swimmers are grouped by the distance they intend to swim, then marked by different colors of swim caps. Running shoes are lined up along the ropes, laces untied and ready for a quick transition to the run.

All body types are represented. Some racers have the built-up shoulders of frequent swimmers, while others have the lean, sinewy build of dedicated runners. Body shape and age don’t deter people from competing; the large number of middle-aged women competing is evidence of that.

To warm up, the racers shake out their arms and legs while ’80s dance tunes keep the energy high. Racers help one another go over the course one more time.

“Bye, ladies!” one woman calls to her friends. “I’ll see you for brunch in a while.”

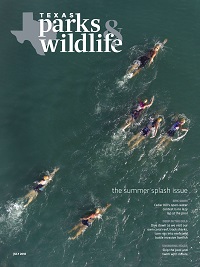

The first group to wade into the lake at the start is the female aquathlon racers, followed by the guys. Then come the female open-water swimmers, again followed by their male counterparts. The water is a bath-like 80-plus degrees — which feels good during the cool of the morning but isn’t ideal after the race gets going. When the starting buzzer goes off, the swimmers dive in, a churning mass of arms and feet, pumped up by supporters’ shouts of encouragement and a blaring soundtrack of Duran Duran’s Hungry Like the Wolf.

For spectators, it’s time to wait. They can’t see how well the swimmers are doing or cheer them on during the race. One swimmer goes off course early, swimming way to the left of the pack, but is quickly redirected by a lifeguard in a kayak.

When the first swimmers come out of the water, shouts of encouragement dovetail with reminders of where the run course begins on hilly South Spine Road. Some racers dry off before pulling on running shorts; others stop only to don shoes before taking off. The cool of morning has already given way to summer heat, and it’s clear the sun will be an extra challenge for the run.

Sweet support

Mejia’s cheering squad is ready when she comes out of the water: “Good job, Les! Keep workin’!” She throws on a shirt, sits down to put on her shoes, then jogs out of the transition area toward the uphill road with barely a moment to catch her breath. She doesn’t look tired. She looks determined.

Then it’s time to wait again. Mejia has 12 people there to cheer her on: husband Oscar, three of her four daughters, several good friends from her Bible study group at Lake Pointe Church and a toddler grandson in a stroller, not quite sure what all this is about. Everyone talks about Mejia’s steady determination.

“She’s been wanting to do this since I was 5,” daughter Carla Keeley says. “This is only the beginning for her.”

As it gets closer to her expected finish time, Mejia’s group gets excited. Laughing and dancing to K.C. and the Sunshine Band’s That’s the Way I Like It, they talk about how she motivates them to live a healthier lifestyle.

“That lady, whenever she gets something in her head, she goes for it,” Oscar says. “She said, ‘I don’t want to die wanting to do this and never trying.’”

First race down

As the racers begin to hit the finish line, we see that this is no walk in the park. Hot and exhausted, some run straight for the shade of a gazebo. Some just stop, bend over with their hands on their knees, then walk it off. One man collapses on the ground, where he is greeted enthusiastically by “kisses” from his dog.

When Mejia’s group spots her starting to head down from the top of the hill, family and fans cannot contain their enthusiasm as they get out their cameras and phones, urging her on: “Yeah, get it, Mom!” “You got this, girl!”

Mejia crosses the finish line with that same look of determination.

She barely has time to catch her breath before she’s enveloped in hugs and kisses.

“You did it!” “I’m so proud of you!” “I love you, Mom!” “You were a beast out there!”

If she’s exhausted, she doesn’t let it show. She grabs some water, drinks a little and pours some over her head to cool down.

The swimming “wasn’t bad,” she says, other than getting kicked. The hills and the heat during the run were the hardest part.

“I saw a lot of people just like me; we had to watch the hills because the sun was beating,” she says. “It was hard, but I did it and I feel good.”

At Cedar Hill, Mejia places second in her age group. Later in the year, she competes in two more multi-sport events, including the Stonebridge Ranch Triathlon in McKinney.

Looks as if she’ll have more epic challenges in her future.

Related stories