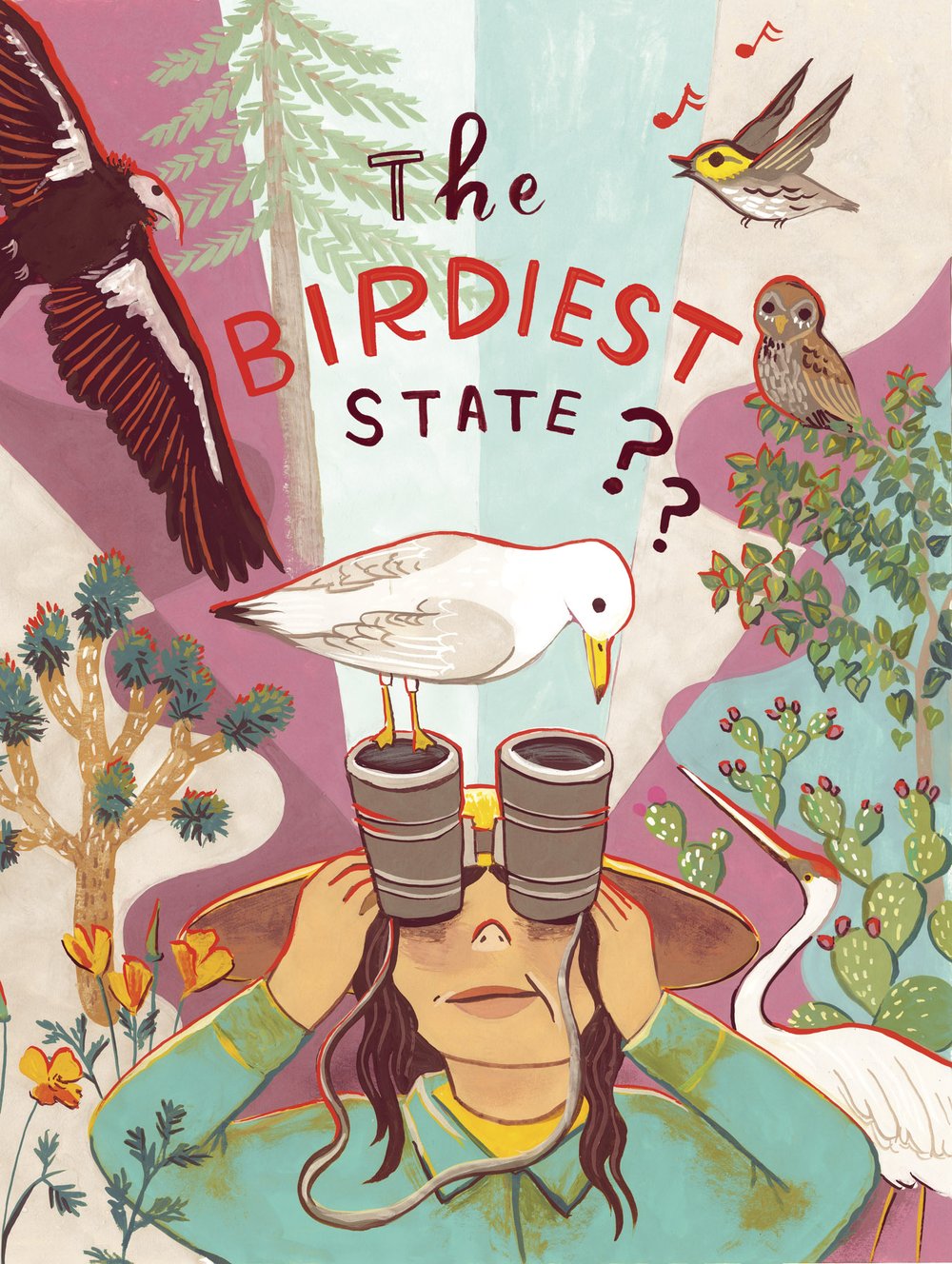

Have you ever wondered which state reigns supreme for bird-watchers? We say that everything is bigger in Texas - not just the world's largest roadrunner in Fort Stockton or the vast King Ranch, but our wildlife and species lists, too.

A devoted bird-watcher corrected me:

“California has more birds than Texas.”

Not wearing pearls, I clutched my binoculars.

How could this be?

The Lone Star State boasts more reptiles, bats and cacti than all other U.S. states, so the answer seemed obvious. Imagine my wilted pride when I came to the painful truth that California claims the title for most species of birds, edging Texas by only a handful of species.

I've explored every corner of Texas, where eastern, western, northern and southern influences converge to create unmatched richness of wildlife. Out of college as a newly minted wildlife biologist, I pulled together a series of talks titled “The Wonderful Wild of Texas” to celebrate our wildlife's remarkable abundance and diversity. In these talks, I would boastfully illustrate our high rank among the lesser states. I pointed to a 2002 NatureServe study demonstrating Texas as the leading state for bird diversity at 477 species. My Texas pride swelled alongside my interest and appreciation for birds. It was during one of these talks with a Master Naturalist chapter that a devoted bird-watcher corrected me: “California has more birds than Texas.” Not wearing pearls, I clutched my binoculars. How could this be?

During the fledgling phase of my bird-watching journey, I learned that many birders keep meticulous records and that many states have organized birding organizations, including a committee that reviews and curates the state's official bird list. This list consists of all species reasonably documented to occur in the state, including uncommon wandering species and naturalized exotics that have been introduced but are self-perpetuating in the wild (like house sparrows and ring-necked pheasants).

I quickly moved through the first three stages of grief (shock, denial, anger) to move into a season of bargaining.

Maybe these official state lists didn't tell the whole story.

Examining the Master Naturalist's claim, I was elated to discover that the Texas list included 636 species in good standing, according to the Texas Bird Records Committee 2010 Annual Report. Still, I became crestfallen when I next read the 2010 California Bird Records Committee Annual Report confirming 644 accepted species. According to the official bird lists, Texas led California in bird species for several years in the late 1990s and early 2000s before California retook the lead in 2003. I quickly moved through the first three stages of grief (shock, denial, anger) to move into a season of bargaining. Maybe these official state lists didn't tell the whole story.

Birdy Giants

As different as our geography and politics are, Texas and California share many characteristics that make both states incredible birding destinations. Both boast enormous populations, sprawling land masses and highly diverse landscapes - from arid deserts to humid forests and from low coasts to high mountains. Both states support birds that breed nowhere else in the world, with Texas as home to the golden-cheeked warbler and California claiming the island scrub jay and yellow-billed magpie. These similarities paint a picture of two nature giants, yet their differences, shaped by cultural identity and position within North America, offer compelling contrasts.

Centrally located within North America, Texas draws from significant continental influences, including the Gulf and three major migratory bird flyways. California benefits from substantial influences of the Pacific Ocean, multiple deserts and mountain ranges, and the Pacific Flyway.

Some of the cultural differences are represented in the state birds. The northern mockingbird, the Texas state bird, embodies fearlessness, resilience and adaptability with a voice that is as diverse as the Texas population. California has the California quail to represent groundedness, innovation and a quirky but beautiful style.

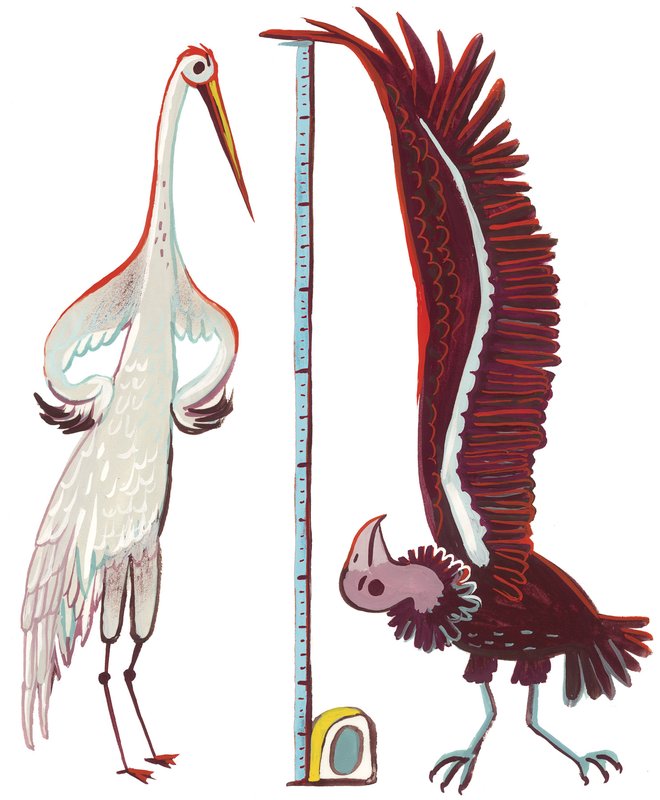

Each state can lay claim to the largest North American bird depending on how you're measuring. While California boasts the behemoth California condor with its nine-foot wingspan, Texas stands tall with the whooping crane, North America's tallest bird at five feet. Once down to 15 individuals, these ghost-white cranes now thrive along the Texas coast.

Another birdy difference is that California has six species of bird named after the state, including the condor and quail, a scrub jay, a towhee, a thrasher and a gull. I reckon Texas wasn't well represented in the bird-naming lobby; none were named after us.

Whatever.

A Look At The Numbers

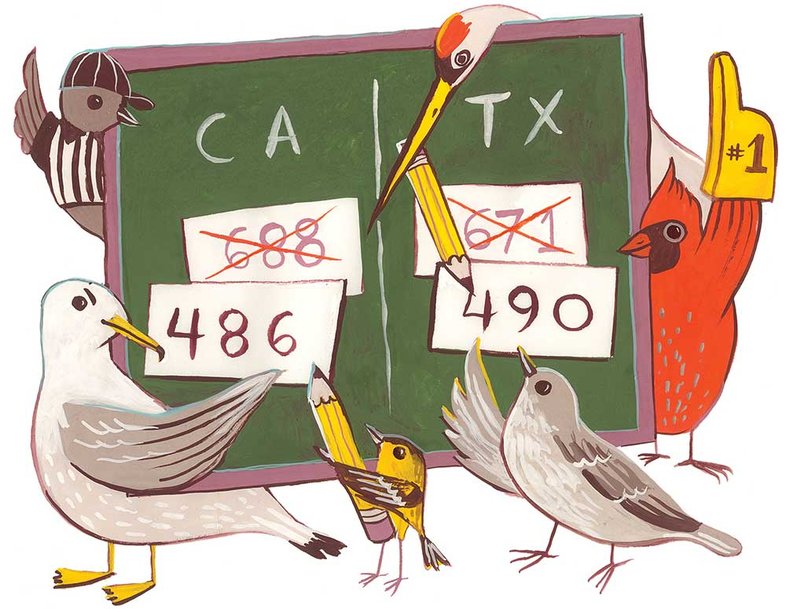

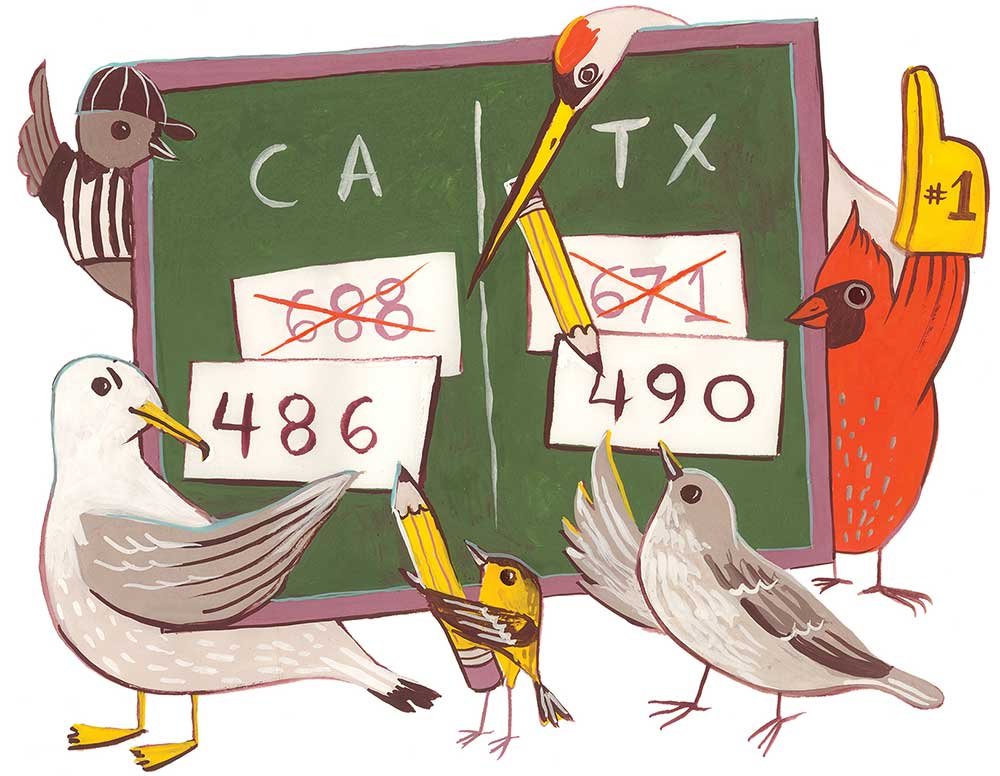

Since the 2010 annual reports, the state bird record committees have added dozens of species to each state's list. Texas currently has 671 species, while California has expanded its lead slightly to 688 species. But not all tics (additions to a birding list) are created equally. Recent additions heavily represent vagrancies, where birders find wayward individuals from far-off regions. Vagrancy is a regular phenomenon among birds but requires uncommon circumstances to become a new state tic. First, a rare bird must be discovered by someone familiar with it or at least knowledgeable enough to know it is not one of the “normal” species. Next, the bird must be appropriately documented, usually with written notes and identifiable photographs or audio recordings. When a report is received, the bird record committee will deliberate to determine whether a new species will be added to the state list. The primary hurdles to adding a species include adequate and clear documentation supporting the identity and determining whether the bird's arrival was most likely natural or artificial (i.e., an escaped pet or artificially transported).

With new species regularly added to each state's list, and with many of these additions representing extremely rare or irregularly occurring species, I've wondered how many of the species on each state's list occur naturally as part of the ordinary life cycle as a breeding, overwintering or migratory species.

Each state's list includes “review species” observed so infrequently that the committee requests documentation to evaluate new records and ongoing trends. By removing each state's review species (185 California species and 173 Texas species) from the state total, the margin closes with California still slightly ahead of Texas (503 vs. 498). Some species on the review list are indeed regular or permanent members of their respective states. One example in Texas is the spotted owl, whose year-round populations are limited to rugged and remote canyons of the Guadalupe and Davis mountains - rarely observed by birders.

I have arrived at the stages of progress and hope ... by excluding vagrant and exotic species, the Texas list (490) surpasses California's (486).

I have arrived at the stages of progress and hope ... by excluding vagrant and exotic species, the Texas list (490) surpasses California's (486).

Taking this pruning exercise a little further, I removed all the introduced exotic species on each state's list (17 California species and eight Texas species), finally delivering the outcome I sought.

At this point in the grief process, I have arrived at the stages of progress and hope after navigating through bargaining and depression. By excluding vagrant and exotic species, the Texas list (490) surpasses California's (486). What remains is a better representation of the core bird population that relies on the variety of habitats within each state and those species that birders most often see.

Birdy Rivals

Although the size of these lists is nearly identical, notable differences remain. Pelagic birds present a unique challenge to birders. Unlike songbirds and waterfowl, members of this group, ranging from open-ocean to near-shore specialists, can spend much of their lives soaring far away from land. Many pelagic species, including shearwaters, petrels and skuas, are most reliably observed dozens of miles offshore over deep oceanic waters. While the Texas list includes a modest splattering of pelagic species, California's positioning adjacent to the Pacific Ocean supports nearly three times as many species, making it a pelagic powerhouse. No problem. Birding from a boat, swaying back and forth open ocean waves while trying to train binoculars on moving targets, is a special kind of birding torture I'm happy to yield to California birders.

Beyond lists, I find solace in the tremendous birding traditions that Texas and California birders share - and fiercely compete over. Take the annual Christmas Bird Counts (CBC), for example. These community science events, administered by the National Audubon Society, recruit thousands of volunteer birders to count birds within 15-mile-wide count circles. Texas and California each conduct over 100 different counts each winter, and Texas' Matagorda CBC regularly leads all others. In 2005, Texas birders with the Matagorda CBC recorded 250 species, establishing the North American record that remains unbeaten today. However, several California CBCs offer stiff competition with counts like the San Diego CBC, which occasionally humbles proud Texas birders by taking the top spot.

Then there's the legendary North American Big Day record set in 2013 by Team Sapsucker from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. This team of birders illustrated a master class in strategic birding by following a 650-mile route through Texas - from Uvalde to Anahuac - observing an astonishing 294 species in a single day. Before Team Sapsucker's Texas triumphs, California hosted the North American Big Day title for decades. The Texas vs. California rivalry extends to Big Year records. In 2021, a Texas birder set a state record of 524 species, well ahead of California's 500 set in 2015 - until 2024, when a California birder reached 526.

Avian Landscapes

Texas isn't just about big bird lists - it's about big landscapes flush with birds. At High Island, I've watched warblers collapse into oaks after a brutal trans-Gulf flight, their tiny bodies quivering with exhaustion. Migration wasn't just an academic concept on sterile pages at that moment - it was survival. In Big Bend National Park, I've climbed canyons in the Chisos Mountains, the air dry with hints of juniper and pine, listening for the Colima warbler's thin, rapid trill - the only place in the U.S. where it is heard. The park ranks fourth in species diversity among national parks, bested only by national seashores where bird diversity and abundance reach great heights. And then there's the Rio Grande Valley, where subtropical woodlands meet the desert brush, drawing birds found nowhere else in the United States. Green jays flash through the mesquite, great kiskadees shout from resacas, and somewhere in the distance, a ferruginous pygmy-owl is well hidden among the oaks and mesquites of the sand sheet. One of my most unforgettable moments was standing in the moonlit brush adjacent to the Rio Grande, listening to the wind pass through the canopy as a mottled owl - the first ever observable in the U.S. - hooted into the night. These aren't just birding spots - they are places where the wild humbles you.

And yet, I can't pretend I'm not intrigued by California, which contains two of the top three national parks for bird diversity, including Point Reyes National Seashore, and legendary sites around Southern California. One day, I intend to see a condor soar over Pinnacles National Park or scan the Pacific for albatrosses, puffins and auklets. If Texas and California can share the title of best birding state - depending on the metric - I suppose I can share a little birding time with California, too.

Ultimately, I've moved from denial to acceptance - California may have a numerical edge, but Texas, with its whooping cranes, golden-cheeked warblers and legendary birding feats, still has my heart — and my binoculars. This journey through grief has taught me birding isn't about winning; it's about showing up, marveling at wild places and embracing a little friendly competition.